Racing improves the breed, apparently. But not sales, as Harley-Davidson found out with the XR1000, which is now a much sought-after rarity and an exciting ride…

Words and photos by Oli Hulme

“Are you going to ride it, then?” grinned Mark when I put away my camera. He had promised me a go, some months ago. “Well, if you’re sure,” I responded. I really wanted to take it to the road, yet I had become acutely aware of the presence the Harley-Davidson XR1000 had, and I had dropped some unsubtle hints about my bad back and that I wasn’t really used to big motorcycles, just in case he had changed his mind and we both had a get-out. This was a genuine rarity, after all. There’s only a few in the world, and a mere handful in the UK. It is also stunning, a head-turner of a machine. Even people who have a hatred of Harleys will recognise how impressive it is, and Mark’s is an absolute gem.

There are some super-sized motorcycles that come across as aggressive. Suzuki’s original 1100 Katana is a sharp-edged example. Laverda’s Jota is a large Italian with a stiletto, Yamaha’s V-Max is almost a cartoon super-villain, and at the risk of offending anybody who will assure me that their own pooch is just a cuddly bundle of fluff, the Harley-Davidson XR1000 is an absolute pit bull of a motorcycle. It is a stone-cold slice of aluminium, cast iron and steel, and to mix metaphors to a ridiculous degree, it’s a back-street zip gun packing a tough guy. Subtle, it isn’t.

“Watch out for the power take-up,” Mark said, reassuringly. “It all starts to happen at about 4000rpm.”

The XR1000 has a reputation for being a bit temperamental from cold, but fortunately, Mark had ridden it to our meeting place, the Beer Shed in Somerset, so the beast had been properly warmed up. I’d heard him coming from a mile away.

Starting was just a push of a button, a traditional but amplified Harley ‘kajunka’ noise, indicating the dramatic throwing around of the engine components and an initial bark that turns into the roar of a P47 Thunderbolt fighter aircraft getting ready to take off. Fortunately, the Beer Shed was closed at that point, so there were no customers to complain about the racket, but the sleepy village nearby was about to have its bucolic calm disturbed. I was glad lambing season had just finished, or we might have had an ‘angry farmer with pitchfork’ moment.

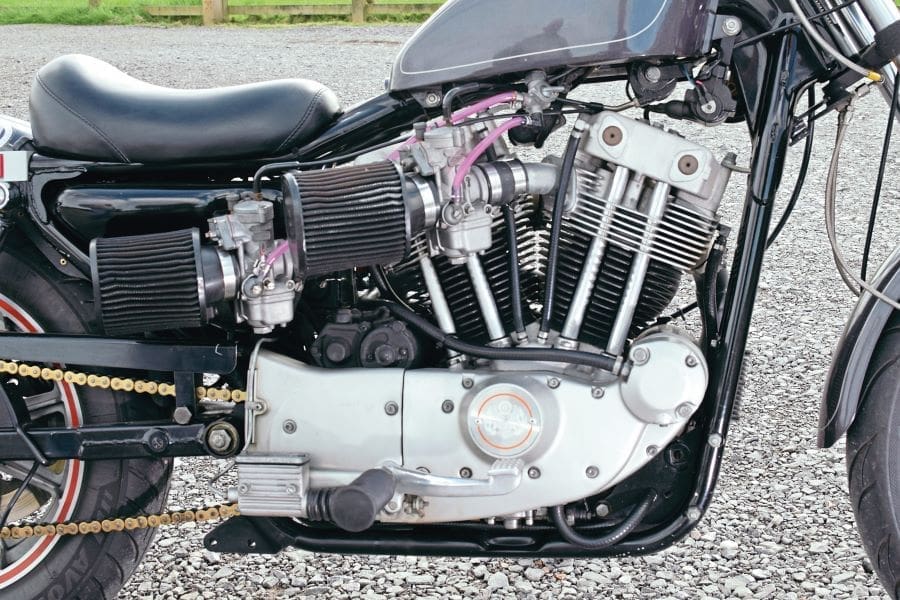

Remembering an early experience with a Jota – if a bike like this suspects you are nervous, then you are in big trouble – I tried to forget all that torque and all those horses making their way to the back wheel, crunched it into first, and negotiated the gravel parking lot. I made for a straight bit of back road, hoping to fool the XR1000 into thinking I knew what I was doing. Onto the tarmac, into second, and whoops, pin back your eyelids – here we go. While it’s not the fastest motorcycle I’ve ever ridden, it certainly feels like it could be. The throttle springs feel as if they are from moped shock absorbers and require quite a firm hold on the twist grip. It has, thankfully, got proper handlebars, which makes handling much easier than Harley’s regular offerings, and there is a decently low centre of gravity, which helps with straight line stability and moderately fast cornering. The shocks and forks aren’t half bad for an early 1980s offering, and the brakes are of the brick wall variety. The riding position is low and dictated by those huge air filters sticking out on the right-hand side. The twin high-level exhausts on the left are well tucked in, which is a relief. Dealing with two hot exhausts burning your left shin while the carbs try to suck your right thigh into a venturi would be hard to cope with. The low height and the length made moving it round from a standstill more of a challenge, and the clutch is moderately hefty, akin to that of a big Italian or Brit, which should be expected.

I rode it round the village a few times. It’s not a friendly motorcycle, but it is surprisingly smooth, with rubber mountings on the ‘bars taking the worst of the vibes out at low-ish revs. Having a hand-built top end put together by a California race shop, rather than something thrown together on a Milwaukee off-day, and then having that engine properly set up helps. It is no ordinary Harley. Nothing shines, nothing is superfluous; nothing is there apart from stuff to make it go.

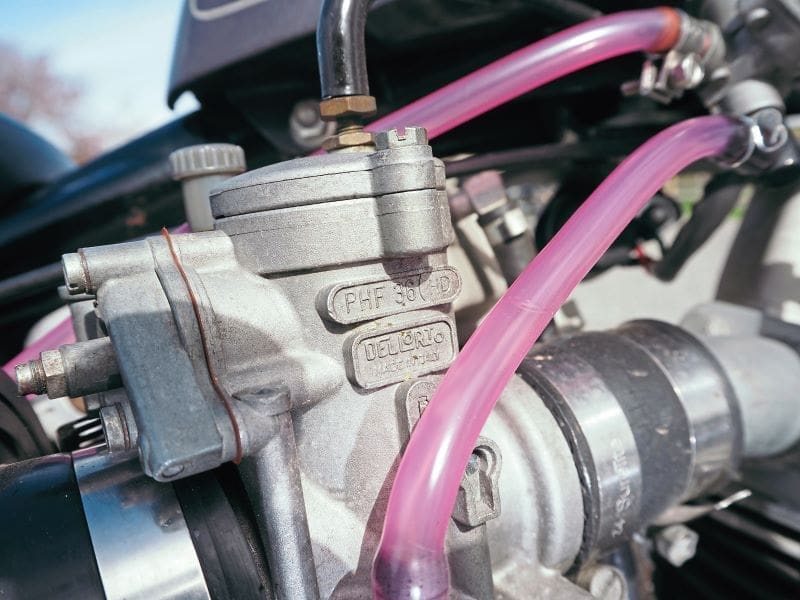

Everything about the XR could be so wrong. There are weird touches – the indicators switches need to be held down to keep them on, so you don’t leave them flashing after a turn, and there is one on each side. The smooth handlebar grips are as fat as drainpipes and a long way from the hefty levers. It’s too loud, too fast, the tank is too small for serious distance, and so is the seat. The riding position would wear you out, the twin Dell’Orto carbs hang off the side as if someone had forgotten to include fitting them into the design until the last minute, and the dustbin-sized air filters are likewise. Why are the pipes so high up? Why is it that colour?

And then you take a step back and look at the way it hangs together. It is beautiful. The most beautiful Harley ever. A Harley into which Milwaukee’s marketing magnates had no input. A Harley built by people who really understood what a motorcycle could be. The XR gets it. And then some.

Building the wildest factory Harley-Davidson

In the early 1970s, when American Machine and Foundry (AMF) owned Harley-Davidson, having a racing team was seen as a good way to sell more motorcycles. This is why there were racing 350cc Harleys in grand prix and, in the USA, a beast called the XR750 that flew the flag in flat or dirt track racing.

The bikes had lightweight, slender frames, powerful engines and no brakes, with riders wearing steel-soled boots for holding the bikes up as they went round left-handers. It is speedway on steroids.

The XR750 was proposed in 1969 and raced from 1970, with a heavily modified Sportster engine featuring a shorter stroke and shorter con rods to take the capacity down the flat track racings capacity limits. In 1972 it got a still-shorter stroke, fatter pistons and a glass fibre rear seat that became the inspiration for thousands of specials builders. Evel Knievel even jumped them over things. To comply with homologation rules, Harley had to sell 200 racing production versions which anyone could buy.

Harley owners who wanted something fast begged AMF to sell a road version of the XR750, but the bosses at the manufacturing behemoth weren’t having it; the XR was for the track. Harley ruled the roost for much of the decade, until Yamaha and Kenny Roberts took the title with an XS650 twin-based racer, and then, in a fit of insanity, a bike with a TZ750 grand prix racing engine.

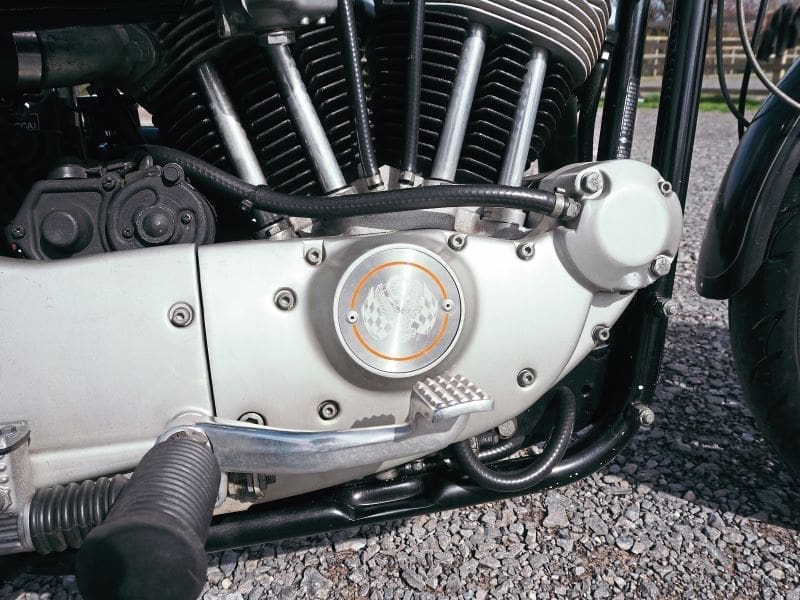

It wasn’t until AMF was bought out by Harley’s management in 1981 that the factory was free to go its own way, and one of the first things it did was produce a road-going XR, the XR1000. From the moment it was first suggested in 1982, it took just two months to come up with a rolling prototype. Unlike the 750, which used an all-alloy engine, this motor was based loosely around the Sportster and had iron barrels but with alloy heads, finished off by tuning wizard Jerry Branch in his Flowmetrics race shop in California, featuring revised combustion chambers, new simple-to-adjust rockers, aluminium pushrods and shorter conrods. The engine had to be short stroke because the cylinder head was taller and needed to fit in a Sportster frame. The barrels had more finning and through bolts running the full length of the top end and barrels. Apart from the purposeful look of the new top end, there were two huge Dell’Orto carbs on the right instead of a single carb in the middle, and the exhausts exited on the left, running high down the left-hand side of the frame. The oil tank had to be reshaped to fit the rear air filter, and the frame was a revised version of the new 1982 Sportster chassis. Much jiggery pokery was then employed to make the bike road-legal in the USA.

By sticking the carbs on one side and the exhausts down the other, the bike became quiet enough to beat the sound meters with stock pipes, and to beat the emissions rules, Harley bolted several lead weights below the engine of the test bike to put it into a heavier weight category. If all the extra attention to the engine wasn’t enough, you could buy a performance kit, boosting power from the stock 70bhp to 100bhp.

The XR1000 looked the part, but the uncompromising nature of the beast meant it wasn’t a huge hit with buyers, though of more significance was the price. When launched in the USA in 1983, the XR1000 had a list price of $6995, almost $3000 more than a stock Sportster, which is a big jump to make. It was also $3000 more than a faster and easier-to-live-with Honda CB1100F.

If you were not wedded to the idea of a super-powered, gravel-snorting behemoth from the Midwest, there was no reason not to buy the more civilised, smarter and more reliable Honda.

Harley shipped 1000 XRs in 1983 and another 750 in 1984, but they hung about in the showrooms for some time and ended up being heavily discounted. As is the way of things, discounted bikes get hacked about and raced, so there are fewer original-spec models than there should be. Of course, if you had bought a XR1000 in 1984 and still had it, the price you could ask would be huge… but it’s doubtful that you would want to part with it.

Mark’s itch

Mark Green’s hunt for an XR1000 got underway when he spotted one in a Bradford showroom as a teenager. “In 1984, I was a 19-year-old with a Triumph Bonneville 650 T120V, the five-speed version with a disc-braked front end,” he said. “I’d had a bad bike smash a few years earlier and spent nearly a year in hospital recovering. When I got out, I got some compensation and bought the Triumph. I was riding about with my mate Pete Randall, who had a 1977 Harley XLH Sportster, and he let me have a go on it – I was 18 when this happened, so I wasn’t quite sure it would be for me, but as soon as I rode it, I thought, ‘I quite like this,’ and it sowed the seed. I sold the Triumph and put as much money together as I could to buy a new Sportster of my own.

“I fancied an XL61 in black. Fran Jessop, who ran Riders in Bridgwater, had one, but it was red, and the only black one I could find was at Steve Rhodes in Bradford, who was a legendary Harley dealer back then. It was going to cost £3850. I arranged to buy it and went to pick it up. I had to promise not to ride it until August 1, because it was registered from then. Steve had a XR1000 in the showroom too, and as soon as I saw it, I thought, ‘I want one of them.’

“Back then, a new XR1000 was £5850, which was a lot of money – a mate had just bought a flat for £17,000. I drooled over the XR though and thought then that I’d have one someday. The XL61 was a great bike, but I did have some trouble with it. Over the years I did not really cross paths with an XR, but it was always on my wish list. I think I only ever saw one on the road.

“When I left work and started at Green Eye motorcycles buying and selling bikes, I always knew that when the time was right, I’d have one. It was my ultimate goal – an itch I had to scratch – and I decided that when I sold my Floyd Clymer Indian Enfield 750, I was going to buy an XR.

“I had joined an XR owners’ Facebook page, and I even offered the Indian as a swap for it but had no takers. Most of the owners were in the US, but suddenly, just after I’d sold the Indian, a bloke turned up in Melksham, Wiltshire, with one he was looking to sell, so I jumped on my XS850 and rode over.

“There it was, the right colour, and all original. It even had an extra set of the original Harley megaphones, and it had 3000 miles on the clock. There was no question – I was having that, and I took it home, put it in the garage, and just looked at it, for ages.

“It was running a bit rough, and when I put the megaphones on, it popped and banged a bit. It needed a tune-up, so it went off for one and it had to go twice before it was right.

“The front brake is really fierce, with those twin discs doing a great job, but you can’t really ride it for more than 45 minutes before it starts to get uncomfortable. It’s incredibly loud, and there’s a fair bit of noise from the tappets too, because it doesn’t have the hydraulic lifters of the Sportster, and the throttle is really heavy, so it’s not the most relaxing thing to ride. There’s a sweet spot at about 55mph, which is when it’s at its most pleasant, but you always feel it is asking to go a lot faster.

“And the amazing thing is that when I take it out, nobody, not even Harley owners, seems to know what it is.

“I’ve always loved the colour, and those touches like the red lines round the wheel rims and the look of the clocks. It looks so good straight out of the box. As long as it’s got the megas on, it sounds incredible too.

“This one, now I’ve got it, isn’t going anywhere. I love all my bikes, but this one, I can’t see me parting company with it.”

■ Thanks to Mark Green, of Green Eye Motorcycles, and the Bason Bridge Brewing Company for its Beer Shed venue at East Huntspill.

Specification

ENGINE: 998cc OHV V-twin BORE/STROKE: 81mm × 96.8mm COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.0:1 POWER: 70hp @ 5600rpm IGNITION: Electronic TRANSMISSION: Four-speed SUSPENSION: Telescopic front fork, twin shock rear BRAKES: Twin 11.5-inch discs front, 11.5-inch disc rear TYRES: Front 100/90×19; rear, 130/90×16 WHEELBASE: 59.3 inches SEAT HEIGHT: 29 inches WEIGHT: 500 lb (wet) FUEL CAPACITY: 11.8 gallons FUEL CONSUMPTION: 46mpg TOP SPEED: 112mph

Owners’ club

Harley-Davidson Riders Club of Great Britain

www.hdrcgb.org