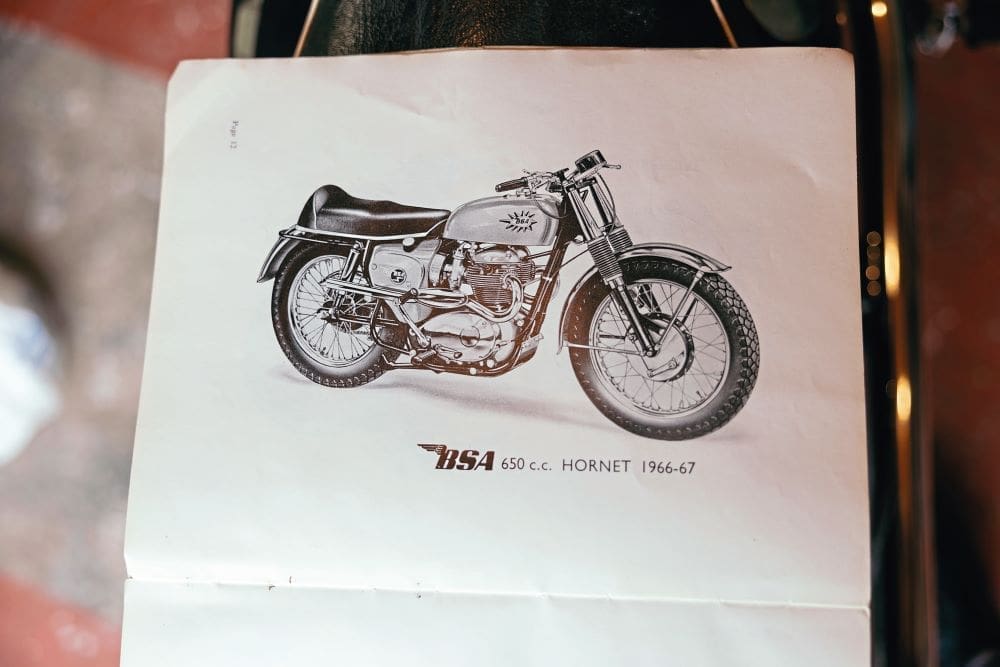

BSA listened to what the US customers wanted and gave them the Hornet. Built for the desert, Steve McQueen was also a fan!

Words by Oli Hulme Photos by Gary Chapman

The greatest years of the ‘Desert Sled’ were all too brief. For a few years in the 1960s, British twins became reliable enough to take on the worst that the California deserts could throw at them. Triumph, Matchless and Norton all produced two-wheeled devices for hooning about in the dirt on. But it was an unsung marketing genius at BSA who got their factory to produce something off the showroom floor that riders could ride seriously. BSA’s unit twin had been a new and different sort of motorcycle from the start. While British rivals either stumbled on with old pre-unit designs or aped their old looks with new unit twins, the BSA engine bore little resemblance to anything else coming out of UK factories.

The engines had styling that was more Italian than British, all smooth curves and polishable casings. The motor had fewer bolted-on bits to shake loose and fall off, and fewer jointing faces than its rivals, with a single rocker cover over the valves, one-piece barrels with integral pushrod tunnels which were short (as seen on the A7 and A10 twins), and long cylinder liners running down into the vertically split crankcase, making for an apparently short engine. There was a strong alloy one-piece primary drive cover and many other sleek additions. It was something of a shock for traditionalists, but away from oily-fingered motorcyclists, the comparative space-age looks were a media hit and the unit twin was a regular feature of Swinging Sixties UK films. The frame, a tidy twin-downtube cradle affair, looked similar to the last of the A7s, and there was plenty of chrome.

However, when BSA moved to unit construction, it had lost its reputation for making snarling off-roaders, in particular the old Gold Star single, and US importers implored the factory to supply something that could fill the yawning gap in the market.

Its first effort to make a factory Desert Sled out of the unit engine was the 500cc Cyclone, launched by BSA in 1964 as a replacement for the Gold Star as an off-road and desert racing motorcycle. Although it was first shown off at Earls Court in the UK, it was the USA where the target market lay. The intention was to take on the two-stroke ripsnorters from Husqvarna and others that had taken on the Gold Star’s mantle, and which had been ripping up dirt on the East Coast and the desert sand on the West Coast, where once the British singles and twins reigned supreme.

BSA created the Cyclone by taking the A50 500cc twin, ripping everything off that wasn’t essential to make it go, and tuning the engine. The Cyclone saw the A50 lose lights, clocks, and silencers. It was given fatter wheels, a pair of Monobloc carbs, and a skinny two-gallon glass fibre petrol tank. ‘Stripped down’ was what the Americans wanted – and BSA gave it.

Shortly afterwards, BSA launched the fire-breathing 650cc Spitfire Hornet twin. The Spitfire name harked back to the US market A10-based Spitfire Scrambler of the late 1950s. The Hornet got leg-breaking 10.5:1 pistons, which gave it power by the handful, a new lightweight alloy head, twin high-level exhausts in its East Coast variant, and low TT pipes for the West Coast. US rules meant you could use the Hornet without lights or, technically, silencers, though both models were supposed to be fitted with baffles to make them road-legal. Whether anyone bothered is a moot point. To provide sparks, there was battery-less energy transfer ignition, and the Hornet came without lights, though there was an option to add somewhat troublesome direct lighting, should the owner desire it. East Coast bikes got a rev counter and West Coast Hornets could have one added as an optional extra. There were beefier tyres, which was what the Americans wanted. It had folding footrests unique to the model, and an also-unique close-ratio gearbox. The new Spitfire camshaft allowed the engine to rev to 8000rpm.

American buyers with pockets full of cash from a booming economy were mightily impressed. Young men looking for excitement fell for the motorcycle in a big way, with sales exploding in the mid-1960s. They bought 10 times as many motorcycles in 1965 as they had in 1960, and many of those well-heeled riders wanted high-performance models they could use in competition.

The Hornet was a user-friendly Desert Sled. While it was a snarling, no-frills off-roader with more than a nod to ISDT competition, the sturdy design made it a superb motorcycle for mucking about in the dirt on. The engine was the top-spec Lightning, apart from the close ratio gearbox. The bash plate and folding footrests were off-road model-specific, and demand for the Hornet was so strong that the factory had none to provide to US journalists, who had to beg them from US dealers.

All was not entirely rosy, however. The professional competition riders found the Cyclone too slow and unreliable in competition and begged BSA to give them back their apparently obsolete Gold Stars, a request BSA agreed to, surprisingly. The following year, the Cyclone name was attached to a more roadster-type model, as well as an off-roader, but as ever, there was no substitute for cubes and it was the latest Hornet, with a slightly longer swingarm, that was making waves.

In 1967, Cycle World declared of the latest Hornet model: “This big Birmingham Firebreather is almost too strong to be believed. Faster in the ‘quarter’ than any other scrambler we have tested and within mere fractions of being the fastest-accelerating motorcycle we have ever tested – period.” The journalists made much of the fact that while the Spitfire Hornet was made in Small Heath, it was not, in their opinion, a British motorcycle.

“The Spitfire is, in effect, a special model made specifically for the American market, tailored to our peculiarly American preferences and riding conditions. In point of fact, North America is one of the few places in the civilized world with enough wide-open spaces to permit full use of the Spitfire’s shattering performance,” they wrote. The BSA Spitfire Hornet, in conclusion, was “the friendliest firebreather of them all.”

The 1967 model had a slightly longer wheelbase, meaning the Hornet could pick its way through rocks and undergrowth with relative ease, while the ability to get the wheel spinning and sliding sideways in a flamboyant fashion was a selling point.

Soon, the Hornet was selling in substantial numbers and the Spitfire name was dropped – not least because BSA had launched a new hyper-fast roadster, the Spitfire MkII. This gave BSA many problems as conrods started to break in the high-performance engines. This took an age to rectify, and frustratingly for the factory, it turned out to be problem that had originated with Lucas, who had changed the points cam profile, causing an extra spark, which overstressed the conrods, causing them to fracture. This dented BSAs reputation as a maker of sporting motorcycles on both sides of the Atlantic.

All the while, the Hornet kept eating up the dirt and plugging the mud. The Cyclone 500 and its replacement, the Wasp, had been dropped in favour of the cheaper to make and more successful B44 Victor Special, leaving only the Hornet as BSA’s twin-cylinder off-roader. This was by now fitted with the Spitfire MkII engine, but used Monobloc carbs, rather than the Spitfire’s Amal GPs. West Coast models were given bigger oil tanks for the final year of Hornet production. The Hornet was then scheduled to be fitted with a slightly milder Lightning engine.

The single-mindedness of the Hornet was pretty much out of date by 1967, with more dual-purpose machines overtaking it – in all senses of the word. BSA responded by replacing it the following year with the stylish Firebird Scrambler, a new model that was more practical and, arguably, prettier. The Hornet’s short life had been a mostly happy one, and it retains its legendary status.

Today, BSA unit twins tend to come in much cheaper than the equivalent Triumphs and Nortons – except in the case of the Hornet and Firebird Scramblers, which have well deserved premium attached.

Certainly, they have their issues, or at least did when they were new, but if those issues weren’t sorted out years ago, the chances are the engine won’t be running anymore anyway.

Max’s Hornet

Max’s Hornet is one of the lovelier A65s you’ll see. It’s a 1966 Hornet East Coast model… except when it isn’t. It was bought from a dealer in imports from Devon. It has the original (and unobtainable) folding competition pegs and a proper Hornet frame, with the all-important original silencer mounting tabs and a few other Hornet specific lugs. The seat is off some other kind of BSA, possibly an earlier Star Twin, or a Wasp, rather than the humped Hornet original. The engine comes from a 1966 Lightning, which bodes well for longevity and usability, and it snarls like a good ‘un through the high-level pipes. Although exhaust baffling is minimal, the Hornet is not as antisocial as you might expect.

One of the many interesting things about this shiny Hornet is right at the front. It’s still got early Hornet fork shrouds, which have been chromed, leaving no place to put conventional headlight brackets. A special US-only BSA aftermarket headlight bracket makes the bike usable on British roads.

It is the front brake that stands out. Instead of the usual BSA front drum, there is a beautifully made and very exotic cable-operated disc. The brake was made by Campagnolo, the renowned maker of the brakes and gear shift of choice for the well-heeled user of human-powered two-wheelers. The cable-operated disc was originally developed in 1964 for Fritz Egli to fit to his Vincent specials. Fritz Egli went to Campagnolo, which was only building parts for bicycles and wheels for Maserati at the time and asked it to come up with something for the Egli Vincents.

Its splendid design has a lovely bit of casting and machining used to mount the disc onto Campagnolo’s own hub. It works by a lever turning a worm drive to move the pads in and out. The Campagnolo discs and calipers were also fitted by MV Agusta in 1967 to its 600cc four, a machine that was no lightweight. Some racers raved about them, and you could buy a Campagnolo set-up off the shelf for Triumphs with a bracket to braze onto the forks, or for Nortons or Ceriani forks with bolt on fixings as they had alloy fork legs unsuitable for brazing. There was even a rear disc arrangement, though very few of these were sold. Most bikes fitted with Campagnolo discs used two, and they have tiny pads gripping the disc. The single disc cost £35 in 1967, complete with the Campagnolo hub, or £50 for a pair. The use of cables on these disc brakes only lasted till 1968, when Campagnolo started to use hydraulics instead.

The caliper is bolted to the front mudguard bracket on Max’s Hornet and the wheel has the matching Campagnolo alloy hub and 18-inch rim. It took a while to set up the disc to work effectively on the Hornet, but now, with a bit of fine-tuning, it will pull the Hornet/Lightning to a halt as efficiently as a hefty TLS drum will. And it looks cool as heck.

There are other unseen modifications which make the Hornet useable. The Lightning engine has a conventional DC alternator and a Motobatt battery so it can run electronic ignition, and many “nice fat sparks” come out of the Dyna high-output coil mounted behind the engine. The headlight is LED. There’s a bigger-than-stock front sprocket on the gearbox. Max says: “It’s a joy to ride – looks good, starts, and runs beautifully now the timing has been properly set up. You can leave it for ages, and it comes back to life straight away. It pulls very strongly at the top of revs, while being nicely usable at midrange.”

That chromed tank is a very recent addition. The original glass-fibre petrol tank leaked a little and looked set to rot even further. A second glass fibre tank was tried, but that item’s modern fuel holding ability didn’t fill Max with confidence, so the Hornet was fitted with “one of those Indian tanks” which cost £180 and is fuel-tight. The chrome is excellent.

Max’s Hornet/Lightning is definitely one of those head-turning motorcycles. He will part with it, if you are interested. He might even sell the front wheel and brake, if an Egli fan is desperate to get their hands on such exotic unobtanium. Email him at [email protected].

But for now, the rasping buzz of this Hornet is going to continue echoing through the hills.

The coolest man of the 1960s rides Desert Sleds

In the 1960s, one of the most popular US magazines for those interested in technology was Popular Science. There were some impressive contributions on a monthly basis. One 1966 edition alone included a road test of the new Ford Mustang, a feature on the SRN4 Hovercraft, a hunt for the Loch Ness Monster, Dr Werner von Braun explaining how NASA was going to put a man on the moon, and the legend that was Steve McQueen tested the BSA Spitfire Hornet, alongside six other off-roaders. And he had some advice for BSA about the Hornet’s stability, which might have been the reason the swingarm was extended by two inches.

McQueen liked the BSA for its power, writing: “The first bike I tested – the BSA Hornet – is designed for desert riding or scrambles, it has a powerful 650cc engine and a damn good air cleaner – real important for hard riding or in the desert.

“It’s important for the longevity of the engine because you don’t have to take the carburettor apart to get the slide unstuck from sand and grit, a problem they don’t have in the east.

“It’s a keen bike. But I found it awfully heavy. A lot of weight would have to be stripped off to make the bike competitive (I prefer a lighter bike, which seems to adjust to the driver; it almost seems to become part of you in the test).

“The Hornet also had a tendency to want to go its own way. I always had to stay on top of it. But it sure had a good-functioning power train. I also think the front forks should be raked on a more forward angle. With this adjustment, the BSA would have a more stable ride in the rough and would be generally a smoother performer.”

McQueen put a Norton-Métisse and a Triumph Bonneville TT Special in the “brute” category and rated a Honda 450 and a Montesa as “keen”, while the Greeves Challenger was “a very healthy piece of machinery.”

His favourite was his own bike, a Rickman Métisse with a 650 single carb Triumph engine he had built with Bud Ekins.

Why did a film star like McQueen spend so much time on motorcycles? “It’s the clean smell of the desert in the morning. The satisfaction of setting up a rig and having it work perfectly in every way.”

SPECIFICATION: (1966 Hornet)

ENGINE: Air-cooled OHV twin BORE/STROKE: 75mm x 74mm CAPACITY: 654cc COMPRESSION: 9:1 POWER: 45bhp @ 6250rpm LUBRICATION: Dry sump IGNITION: 6v Lucas points CARBURETTOR: Amal Monobloc 389/689 (stock)/Concentric 930 30mm (later models) TRANSMISSION: Triplex chain GEARBOX: Four-speed foot change FRAME: Twin downtube duplex cradle FRONT SUSPENSION: Telescopic forks, hydraulic damping REAR SUSPENSION: Swinging arm, twin Girling three-position shocks FRONT BRAKE: 8in sls drum (stock) REAR BRAKE: 7in sls drum TYRES: West Coast 3.25 x 18 front (East Coast 19in) 3.50 x18 rear WHEELBASE: 54in GROUND CLEARANCE: 7in SEAT HEIGHT: 31.5 in DRY WEIGHT: 390lb TOP SPEED: 108mph