Most classic enthusiasts will be aware that Triumph created the Trophy range from the three machines that the experimental department had converted for the 1948 ISDT by adding a few lightweight parts to the Speed Twin roadsters. The bikes were good enough to earn the British team gold medals but not as good as they could have been. Triumph listened and the production Trophy was a much better machine capable of good all-round performance and, probably most importantly, Triumph felt it had the bike to tackle the important USA market.

On the other hand the Métisse grew from the efforts of Don and Derek Rickman to gain success on the scrambles scene. Like a lot of people, the brothers found that the standard factory supplied products were a bit lacking in some areas so built their own ‘bitsas’ from the best components around at the time. How they came on the name Métisse – come on, we know that métisse is French for ‘mongrel’ – as a model name I’m not sure but it certainly sounds much more professional than ‘bitsa’. The first versions had BSA Gold Star frames carrying T100 engines but eventually the brothers built their own frame and added the distinctive, easy-to-clean, plated finish.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Unlike the Trophy and even the Gold Star which both had a roadster base, the Métisse chassis was uncompromising for the scrambles track. There are no concessions on a Métisse, nothing on there that doesn’t do a job, if a component can be made to do two jobs then so much the better. Over the years I’ve been riding motorcycles I’ve been lucky enough to ride a few Métisse models in scrambles and often wondered just how they’d stack up as a road bike. When I spoke to Robin James at Red Marley Hill Climb he mentioned that in his workshop he had just such a beast. A road converted Triumph-engined Métisse scrambler that he was sorting out for a customer and it could be available for a test if I fancied. Hmmm, let me see… I could be rinsing a few things through, or possibly washing my socks… oh go on then, I’ll put all that aside and have a ride on the Métisse.

Unlike the Trophy and even the Gold Star which both had a roadster base, the Métisse chassis was uncompromising for the scrambles track. There are no concessions on a Métisse, nothing on there that doesn’t do a job, if a component can be made to do two jobs then so much the better. Over the years I’ve been riding motorcycles I’ve been lucky enough to ride a few Métisse models in scrambles and often wondered just how they’d stack up as a road bike. When I spoke to Robin James at Red Marley Hill Climb he mentioned that in his workshop he had just such a beast. A road converted Triumph-engined Métisse scrambler that he was sorting out for a customer and it could be available for a test if I fancied. Hmmm, let me see… I could be rinsing a few things through, or possibly washing my socks… oh go on then, I’ll put all that aside and have a ride on the Métisse.

Uncompromising engineer

Robin’s restorations are well known in the old bike world as being top-notch stuff, he is an uncompromising engineer who will not settle for second best. As he says, his work often has to go to the far side of the world and it’s not always easy to fix things thousands of miles away. “I like them to be right when they leave us and a bike going overseas, as this one was to be, will get a full 500-mile shakedown test so we know it will be right.”

Robin added that they’d had this particular bike for some time and were doing a sorting out on it. “It’s one of the services we offer to clients, they’ve maybe bought a bike and it’s ok but not just quite right, so we can do the little fine tuning jobs that make the difference between a good bike and a fabulous bike. You know what I mean, making sure the clutch lifts cleanly and smoothly, that it goes in and out of gear easily and set up the suspension and carburetion,” he says. “Essentially it’s what we do after we’ve restored a bike fully in our workshops, because the work isn’t finished when the last nut and bolt is done up,” he adds.

Test Mileage

For machines that are going to stay in England the test mileage is lower – around 250 miles – though the team at RJES will test a bike until they are happy with it rather than stop at a pre-set limit. “So,” says Robin, “I’ve done less than 100 miles on this bike, it isn’t perfect yet but it’s not bad.” He goes on to tell me that it is for an American customer and he wanted a bike in the flat track/desert racer style that he could use on the road and the bike came to Robin’s place just as it is. “We’ve not had to strip it or anything like that – this is purely a sorting out exercise,” he says. “What’s gone before is of little interest to us really and the history of a bike starts when we see it and our first task is to assess the job and see where attention is needed.” I asked him if he had a particular method of working, such as always starting at one end and working his way through from there? “No, not really, in this case the major problem was to correct the 40 thou’ run out in the rear sprocket.

Now, 40 thou’ might not sound much but it’s enough to shorten chain and sprocket life, so this was where we started. I had a similar problem originally with same BSA qd type sprocket carrier and drum on my Goldie scrambler that you dirtied for me at Red Marley. It too had a bit of run-out but the way I corrected that was simply to make up a complete new fitment in alloy. It was quick to do and halved the weight of the rear wheel,” he laughs.

Now, 40 thou’ might not sound much but it’s enough to shorten chain and sprocket life, so this was where we started. I had a similar problem originally with same BSA qd type sprocket carrier and drum on my Goldie scrambler that you dirtied for me at Red Marley. It too had a bit of run-out but the way I corrected that was simply to make up a complete new fitment in alloy. It was quick to do and halved the weight of the rear wheel,” he laughs.

The alloy route wasn’t an option here though as the bike wouldn’t be maintained at the same frequency as a competition mount so the 40 thou’ mismatch had to be corrected by careful machining of the standard parts that would stand up better to the longer service intervals of a road machine. While the sprocket was off though it went to the drilling machine and had some lightness added. “It saves a few grams at least,” says Robin, “but it looks better too. While we were at it we made a new spindle for the hub, the one on was just a touch too loose a fit for my liking.”

Start road testing

He goes on to say that the only other thing he had to attend to before heading out to start road testing was the steering stops. The bike came with the rubber bump pads apparently favoured by the scrambles scene in the 60s. This too wasn’t really an option on a bike destined to spend most of its life on the road. Robin set too with some tube, round bar and the brazing rods to create these neat, simple and effective stops.

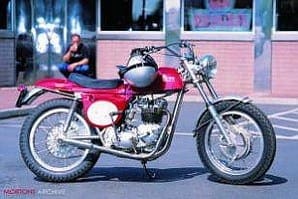

My first ride on this attractive machine was to be a relatively brief one as the only possible location for photographing such a bike had to be the American-style diner virtually round the corner from Robin’s workshop. In so much as it is possible to gain an impression after 500 yards my first thoughts were, ‘wow, what a roomy bike’ and ‘aren’t the bars wide.’ Not that this is a problem for me as it’s much my preferred style of motorcycle. Café racers are ok, but few of them fit me since Mrs Britton’s little lad gained an inch or two in the waist department.

My first ride on this attractive machine was to be a relatively brief one as the only possible location for photographing such a bike had to be the American-style diner virtually round the corner from Robin’s workshop. In so much as it is possible to gain an impression after 500 yards my first thoughts were, ‘wow, what a roomy bike’ and ‘aren’t the bars wide.’ Not that this is a problem for me as it’s much my preferred style of motorcycle. Café racers are ok, but few of them fit me since Mrs Britton’s little lad gained an inch or two in the waist department.

Along at the OK Diner manager Liz Price was quite happy to let us stand outside in the hot sunshine and photograph a bike in the parking lot. As photographer Haskell clicked away, asking first to move the bike this way and then that way and if I needed any special shots Robin ran through the spec of the bike for me. First of all the frame is distinctive and typical of the Métisse style and it wears Ceriani suspension at both ends. This surprised me, as I didn’t realise that Ceriani made rear units, though I suppose if they make front forks then rear dampers shouldn’t be too difficult to do. Up front the huge drum brake is Italian too, but from Grimeca, four shoes are in there and are bedding in nicely. Completing the polished image is the flanged wheel rims and both are 19in, the back one wearing a Pirelli that looks to be a flat track type and the front has a K70 Dunlop, both add to the feel of the desert or flat track racer but the image of the whole machine has to be the distinctive red tank, seat and sidepanels.

Mouth-watering

Mouth-watering

The impact the image must have made on the scene in the 60s must have been incredible; it’s stunning now, 40 years on. To be honest the whole mouth-watering looks and my 500yd ride had me gagging to be on it, but Haskell wasn’t being rushed. Eventually though he was happy with the statics and wanted some riding shots. Oh, yes! I thought. On with the helmet and astride the bike.

As it is a Triumph I pulled in the clutch and swung on the kick-starter to free off the clutch. Petrol on, flood the carb slightly and no ignition switch to worry about, it’s all direct. No heavy battery or anything else just power from the alternator to the Boyer Bransden box of tricks. Bring the engine up to compression and press down on the kick-start. No lunging or huffing and puffing, just a firm thrust and the engine snarls into life. Yes, snarls. Just look at those shorty silencers. Yes, you could argue that the sound is loud but in a typically British way, not painfully loud. Anyway, it settles down to a nice tickover, needing only a few blips of the throttle to keep it going until it warms up, this didn’t take long on such a hot day.

Other than it being a 750cc 10-stud top-end on 650cc crankcases Robin has only the briefest idea of the engine make-up. “Like I said earlier, I’ve not had the unit apart so don’t know what’s inside,” he says. I’m going to make an educated guess here and say that it seems to be in a fairly high state of tune owing to the harsh feeling of power delivery. Crack the throttle open and the instant urge is there, a feeling of wanting to get on with it and woe betide the rider who hangs back. Clutch action is fairly light thanks to a bit of attention to the cable run, and down into first happens with a click not a graunch.

As I ease out of the diner car park and onto the Leominster bypass, I’m into second just before the roundabout and already the comfortable riding position is paying dividends. No struggling up from the fork spindles to try to catch a glimpse of the road as would be on a café racer, no siree! The wide bars promote stability as I almost casually glance over my right shoulder and accelerate into the roundabout before selecting third and powering out of the other side. Like the rest of the UK Herefordshire has its share of road works and the prospect of a decent blast along a straight road before a nice sweeping bend was thwarted by road works, and testing out top I’d to snick back down the box and, out of perverse interest to see if it would do it, come to a stop before selecting neutral. Like many of you reading this I normally like to be i n neutral before coming to a halt as this is the time-honoured way to do it, though I’m sure it has more to do with incorrect clutch adjustment than design faults. Anyway, at rest a slight click up and I could let go of the clutch lever as the lad on the stop/go sign talked to his buddy by radio and allowed a stream of cars to pull through.

n neutral before coming to a halt as this is the time-honoured way to do it, though I’m sure it has more to do with incorrect clutch adjustment than design faults. Anyway, at rest a slight click up and I could let go of the clutch lever as the lad on the stop/go sign talked to his buddy by radio and allowed a stream of cars to pull through.

Soon though it was my turn again and first gear slipped in quietly and off I went. There is a strangish sensation of nothingness where a petrol tank should be as the Métisse has a very slim fuel holder and it’s low down in front of the rider. The bars seem to add to this sensation as they make the rider sit back, almost chopper style, where European scrambles bars would have the rider forward a little more. Not that this is a problem and a quick check of some old dirt track racing pictures show that on the race tracks of the USA this style of bar was popular with certain riders.

“Is it one for you Tim?” asks Robin as I ride into his yard. “Could well be,” I grin, “why, is it for sale?” Robin nods and says, “it’s a possibility, and the owner might be persuaded.” Perhaps another one to add to my list of ‘what to do with a premium bond win’. ![]()