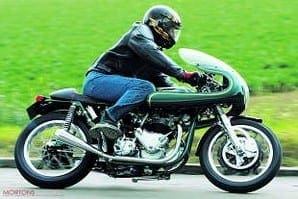

Griff Jones’s Triton is built in the classic cafe racer style that Griff would have been familiar with as a youngster in London riding to all the local haunts such as the Ace Cafe. Towards the end of the show, when I managed to get more than a brief word with him, he told me it was styled after the Triton he built in the 60s. “It’s my first British bike for 27 years,” he added, “though I’ve always kept up with the classic scene, helping friends build bikes and the like.”

The Norton Featherbed frame will take an amazing amount of engine and gearboxes quite easily and the easiest option of all, the Triumph power train, slots into the Featherbed frame and looks like it has always been in there. But you’re not obliged to stick with that format as BSA and AMC/Norton gearboxes are very good, so, if you’re mixing and matching, why not go that extra bit? A lot depends on finances and ability as to the final choice, one that was already made for Griff by the previous owner. “I’d looked at one or two bikes before getting this one and admit that I bought with my heart rather than my head as it belonged to the widow of a bloke killed when a car pulled out in front of him.”

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

He said he’d seen his original one in a dealer advert in the classic Press some years ago but didn’t chase it up. “Maybe I should have,” he said, “but I didn’t. I’d often thought about building a similar one though, with the benefit of hindsight after I did the engine on a TriBSA for a friend, I decided that I wanted a Triton again.”

The basic combination of parts – Slimline frame, Norton gearbox and Thunderbird engine – was already made and Griff bought the bike in one lump. “It also had the belt drive on, alloy tanks, which may possibly be Unity ones, and the obligatory rear-set foot-rests mated to clip-on handlebars. When I got it home I realised just how it had suffered during its racing career.”

The basic combination of parts – Slimline frame, Norton gearbox and Thunderbird engine – was already made and Griff bought the bike in one lump. “It also had the belt drive on, alloy tanks, which may possibly be Unity ones, and the obligatory rear-set foot-rests mated to clip-on handlebars. When I got it home I realised just how it had suffered during its racing career.”

He told me not only was the frame twisted but there was damage on the bottom frame tubes, the forks were bent and one of the yokes was cracked.

Anyway, filled with eager enthusiasm, he ripped the lot apart in one go. “Maybe I should have taken pictures but I was in too much of a hurry. I suppose that, because the idea was to do 2004 version of my 60s bike, I already knew what I wanted it to look like and the rest was just down to detail.

Blast cleaning

“My first task was to sort out what needed replacing and what was repairable. Blast cleaning the frame showed up the tube damage and that was the first job. While I was at it I cut off all of the mounting brackets so I could start again.”

His reasoning behind this is a good one as, if the standard brackets are left, then there is a danger that you’d compromise the design and use them to mount things rather than fixing new brackets on and having things where you want them. Binning the bottom yoke wasn’t a hardship either as the design called for an alloy one anyway. Also dumped were the clip-on ’bars. “They were bent and I’d seen some in CBG that looked great…”

With the damage repaired and the other parts replaced, the rebuild began. The finish was always going to be the Rootes Sherwood Metallic Green that his original was finished in. “There was some in the garage where I worked back then, probably off something like a Humber Sceptre, though more than a few people have doubted the colour and many a know-all has said “couldn’t get those fancy colours then”. I’ve given up arguing and I don’t really care; I know it’s a genuine colour.”

With the damage repaired and the other parts replaced, the rebuild began. The finish was always going to be the Rootes Sherwood Metallic Green that his original was finished in. “There was some in the garage where I worked back then, probably off something like a Humber Sceptre, though more than a few people have doubted the colour and many a know-all has said “couldn’t get those fancy colours then”. I’ve given up arguing and I don’t really care; I know it’s a genuine colour.”

Up at the front end new stanchions fit into the alloy yokes and the sliders have new springs, bushes and seals on the inside and the biggest, baddest drum brake I’ve seen in my life on the outside! It’s bloody huge. Sort of like grabs a hold of your eyes and drags them to look at it. “It’s a Degens four leading shoe racing one,” said Griff. “Saw it for sale and had to have it. Mind you, it didn’t look like that when I got it.”

There is a lot of this bike that Griff’s simple statement can be applied to, as few parts are as they were when he bought them. Apart from the brake, which needed a considerable amount of work to get it up to scratch, he fabricated things like the foot-rest hangers, rear brake lever and the linkage for the Norvil gear lever. “Some of the stuff would have been OK to leave as it was good quality, but it didn’t quite fit what I was trying to achieve,” he said. “I wanted to tilt the engine forward in the frame a bit so I had to make the engine plates to do this. But, as a knock-on effect, you can’t buy exhaust pipes that allow for a tilted engine, so I had to make my own.”

He said all this matter-of-factly, as if it was easy to do and get right. “The megas came from Unity in Lancashire. Unlike the ones I made in the 60s, these have innards, so are more acceptable,” he grinned.

Another little tweak cut down on the noise for town riding: Griff installed throttle valves at the front of the megaphone. A simple cable and lever arrangement allows him to close them for town riding and open them for more performance.

“When I bought the bike I was given a lot of information with it, things like settings and timings for the engine, all that sort of stuff that seems simple but is a great help when you come to rebuilding.”

As Terry snapped away and we had to shift the bike this way or that for the right light, Griff continued: “I put the engine back together with the same spec as it came, though some parts I’m not sure about.”

Norton crank

For instance? “Well, I think the cams are full race ones but what make or lift I don’t know. I do know there is a Norton crank with T140 con-rods fitted to it. The barrels are 10-stud T140, overbored by 20 thou, and I’ve got 10:1 pistons in there, which bumps the capacity up to 820cc. The head is fairly standard – even the ports are as Triumph made them – though it was all converted to use unleaded fuel before I got it.”

He told me Bassett Down did the balancing work and matched the rods to the crank. Griff made the engine breather and assembled everything using the build notes supplied. “Fairly wild cam timing, too,” he said, “but I used it thinking that I’d try it and see what it was like knowing I could easily alter it.”

He told me Bassett Down did the balancing work and matched the rods to the crank. Griff made the engine breather and assembled everything using the build notes supplied. “Fairly wild cam timing, too,” he said, “but I used it thinking that I’d try it and see what it was like knowing I could easily alter it.”

“What’s in the gearbox?” I asked him.

“Standard Commando cluster, four speeds, and it was in good condition. All I’ve done is change the selector springs and convert the clutch pushrod to oil seal so it doesn’t leak on the belt primary.”

The belt drive is another unknown quantity – it might possibly be a Tony Hayward one, so Griff has described it to Tony, who thinks it could be an early version. It works well, it’s light and neither slips nor drags. It also means that no primary case is needed and Griff made up the neat alloy shield, getting Alan at Stockholding Engravers to add the lettering. By this time our photographer was wanting to get some action shots, so Griff quickly added that there was a new three-phase alternator powering a Boyer electronic ignition system, so starting shouldn’t be a problem. The whole bike is bolted together with stainless steel fasteners and those not made by him were sourced at Custom Fasteners – good quality he says – but few have not had an extra bit of attention from Griff – even if it was just polishing.

One of my major bugbears about cafe racers is that I don’t always fit them. For some reason I’m a different shape in my 40s to the one I was in my 20s – especially around the middle. However, I had better hopes for this one as Griff is a little taller than me and the bike is built for him. And so it proved. There was none of the ‘knees around my neck’ feel to this bike. As expected, kick-starting was easy, a little flooding and a firm kick from cold is, in my experience, very good. I did as told and blipped the throttle until the engine warmed up, after which it would tick over.

Just before I pulled away, Griff told me to watch the front brake: “It’s not as good as it might seem for such a big unit. In fact, I was very disappointed first time out and thought I’d set it up wrong. I rang up Dave Degens, told him what I’d got and what I’d done and he told me that it was spot-on and all I had to do was leave it. It would bed in and get better. I wasn’t convinced but it is a hundred times better than it was at first so, by the time I’ve a couple of thousand miles on the clock, it will be even better.”

Clicking into first gear, I pulled away into rural Bedfordshire and tucked behind the Commando fairing. Going up through the gears was incredibly easy and the 820 motor seems to have plenty of pulling power, despite the hot cams. Finding a straight stretch of road and having nothing behind me, I tested the brakes so I knew what to expect should an emergency arise. The back one was brilliant but I could appreciate how he felt about the front one. As the test went on, though, I could feel an improvement in its effectiveness. I’d say he’s right about it taking a couple of thousand miles to settle down properly – not that it was terrible, just a bit wooden.

Like all country roads, this one has its fair share of ripples and it was on some of these that Griff’s other concern showed its head: the forks topping out. The action and damping is great but there is a definite clunking when the road surface gets rough. It doesn’t cause any problems or muck the handling up, but if anyone knows why Roadholder forks top out, or even better can suggest a cure, then let Griff know. The rear end of the machine has no such problem and the Koni Dial-a-rides are brilliant. When a bike works like this one does the rider tends not to notice how it is working, merely getting on with enjoying it, so if I say that I reckon the controls are good it’s because they worked without fuss and you’ll have to trust me on it.

Like all country roads, this one has its fair share of ripples and it was on some of these that Griff’s other concern showed its head: the forks topping out. The action and damping is great but there is a definite clunking when the road surface gets rough. It doesn’t cause any problems or muck the handling up, but if anyone knows why Roadholder forks top out, or even better can suggest a cure, then let Griff know. The rear end of the machine has no such problem and the Koni Dial-a-rides are brilliant. When a bike works like this one does the rider tends not to notice how it is working, merely getting on with enjoying it, so if I say that I reckon the controls are good it’s because they worked without fuss and you’ll have to trust me on it.

No missed gears or coughing under acceleration either, and minimal vibration from the pre-unit engine. With twin carbs fitted, this suggests that they are in balance, because if you’ve ever had the misfortune to ride a bike with the carbs out of balance, you’ll know about it – so will your dentist as he rebuilds fillings.

When I pulled over to the side of the road after enjoying Griff’s bike for most of the morning, he anxiously asked what it was like. Almost before I could get my helmet off he was saying that, after his first ride on it, he was up for selling it as it felt so rough compared to the Japanese bikes he’s been used to. “No, look, it’s fine, it’s smooth and quick enough,” I told him.

“I was just worried, that was all,” he said. “It’s nice to hear you say that as you’re the only other person to have ridden it and it’s my first Brit bike in 27 years.”

Yes, you do have to accept that you’re not going to get turbine smoothness with a vertical twin but, if you think all Brit bikes have to be unreliable oily nails, then take a look at Griff’s bike. This is how it should be and there are no rose-tinted specs here. ![]()