The Japanese take on big parallel twins was something of a mixed bag. Despite the successes with two-strokes and air-cooled fours, the lure of the big twin proved too much. Two of the major players developed new versions of the same theme, one carried on with an existing design while the fourth came at the concept from a different angle.

Kawasaki’s Z750 was a bold attempt at reworking the basic concept. Double overhead cams, electric start, CV carbs, twin engine balancers and a reasonably low slung mass. Great, but just like the company’s 400cc twins the bigger bike was seen by the press as a little too sensible. Its faults, real or imagined, were blown out of all proportion and UK sales were small. In the States, it was the fourth best seller for Kawasaki for several years running, so maybe it was just us.

Fitted with twin balancer shafts to numb the worst of the engine configuration’s inherent vibes the bike was actually one of Japan’s better big twins. It was faster, more reliable and better handling than its predecessors, but it still didn’t find enough buyers. Initially offered from 1976-1980 the bike reappeared in the UK in 1982 when someone who should have known better reckoned there was a market opportunity that was never going to happen.

Honda’s dalliance with the big twins had brought a better than lukewarm response with the CB450, aka The Black Bomber. Although never desperately successful in the UK, the bike had a strong customer base in other markets and particularly in the USA. Conscious that middle weight sales success normally generated substantial profits Honda elected, for the 1975 model year, to revamp the 450 into a full bore 500, the CB500T. In fact the bore stayed the same; it was the stroke that increased along with a move from a roller to ball journaled bottom end. The bike received a full on restyle and became a little more traditional in appearance. Huge silencers and a deep seat combined with higher bars to suggest this was a relaxed, gentleman’s machine. Yet again stateside sales were strong and the bike remained on sale until 1978.

Its reception in the UK was less than friendly. The road testers of the time were surely wearing rose-tinted goggles when making covert analogies to a T100 Triumph and the like. Of course the Honda didn’t have the same level of handling or style but it was unarguably better engineered and more reliable, especially in the electrical department. However, the best own goal scored had to be the colour schemes offered by Honda. Either dark metallic brown or a worrying pinky red – neither option found favour in the home of big twins. Add in a brown seat and a disc brake that didn’t rust at the first sight of rain and the CB500T was effectively a non-event in Britain. It would be the late 1990s before a water-cooled, eight valve, CB500 was launched.

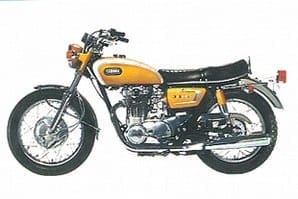

If any manufacturer was truly, madly, deeply in love with the big parallel twin it was Yamaha. The combination of impending anti-two-stroke legislation and the runaway success of the XS650 convinced the company that the future lay with four-strokes and in Yamaha’s case it was twins all the way. Sadly none of the initial follow-ups to the 650 were any good.

The TX750 was a brave attempt and for once a balancer system actually smoothed the big vibrations to the point where the press hacks genuinely commented that the bike felt like a four. Unfortunately the very same balancer whipped the oil to foam causing lubrication related reliability issues. Adding insult to injury the balancer chains had no means of adjustment which then led to the actual balancers being out of phase thus precipitating the very vibration they were supposed to have eradicated. Within two years the TX750 was swiftly put to sleep.

Given that Yamaha envisaged running both 650 and 750 twins it made sense to have a middleweight as well and TX500, with a 180º crank like the CB450, seemed to suit this remit perfectly. Alas the firm’s aspirations were beyond its abilities and the bike was beset with issues. Poor running, transmission issues, blowing head gaskets and a lack of low to middle range torque all failed to threaten Honda’s Black Bomber.

On paper the eight valved DOHC motor should have aced everything in its path but all those design oversights and mid-1970s metallurgy compromised the bike’s potential. So two apparently innovative Yamaha twins were nothing but headaches. Yamaha dropped the TX prefix along with the 750 into the scrap bin, reworked the half litre twin and sold it as the XS500. Updated, boxy styling and substantial revisions in the motor distanced the bike from its TX roots but success still eluded it. It wasn’t a patch on the RD400s of the day and the press were quick to marginalise it as an also ran.

Suzuki had the good sense to keep out of the melee until 1983. The GR650 Tempter was a brave take on the concept and the result was a very capable machine but history shows it was never a big seller. Suzuki had enjoyed reasonable success with the GS400, 425 and 450 but the GR was a completely different approach. The 650’s motor was significantly narrower than the 450 and only two inches taller yet the cylinder head had 50% less moving parts. The hollow cam shafts were a first for Suzuki and typified the company’s approach to the GR; new thinking applied to an established concept. Everything possible was done to keep the machine’s mass as low as possible including computer analysis to remove excess weight from the engine castings. With careful thought and design applied to the chassis Suzuki had a 650 that handled like a very nimble 500cc four-stroke twin.

And the techno-fest didn’t stop there. The motor used an oil jet system to cool the underside of the pistons. A gear driven balancer shaft was added to help overcome vibration. Add in twin swirl combustion chambers (TSCC) or ‘Twin Dome’ as it was billed in this case and the bike was evidently well specified. But all of this was nothing compared to the ace that Suzuki held up its corporate sleeve; a variable mass auxiliary flywheel. A one-and-a-quarter kilo centrifugal clutch on the left-hand end of the bike’s crank was intended to give rider the best of both worlds; the bottom end grunt and driveability of a big parallel twin at lower speeds with the more rev happy nature of a four at higher engine speeds.

The extra mass effectively clamped itself to the crank below 3000rpm giving the bike the extra grunt and pull expected of big twins while also helping to damp out the uneven firing pulses intrinsic to a 180º twin. Which resulted in a machine that delivered peak torque at 3500rpm and kept some 30lb-ft of torque coming all the way up to seven grand where peak horsepower was delivered. A certain success then? Er, no. Poor comfort and so-so handling restricted the model’s appeal. Quite possibly all the R&D budget was blown on the motor, leaving precious little for anything else.

With the possible exception of the XS650 none of the big parallel twins from Japan did well. Why? In all honesty the Japanese were probably victims of their own success. The world had moved on and the cachet of the big twin was just an anachronism, a recent memory. Riders wanted four cylinder machines, technological marvels, sophistication and something just a little bit special. All of the contemporary big twins were old hat and perceived as the past, not the future. It would take almost another generation before the concept once again found favour. BMW’s F800, Yamaha’s TDM850, Triumph’s Hinckley Bonneville and Kawasaki’s W650/800 all sell successfully to niche market applications. The fact that Yamaha invested colossal sums in the Super Tenéré’s development might suggest there’s life in the old dog yet. Just think, 1200ccs, DOHC, 110bhp and lashings of torque; anyone fancy dropping the motor into a Featherbed? ![]()