The shaft-drive Sunbeam twins don’t sit easily with the ruffty tufty vision of 50s motorcycling, when young men supposedly roared across the countryside on Norton Inters, Triumph Thunderbirds and BSA Gold Stars with not a care, or a speed limit in the world of the open road.

The rose-tinted spectacles of hindsight are very narrowly focused and overlook the commuters putter-putting their Villiers-powered way to work, the family men who relied on a rugged side-valve single to pull a sidecar load of family to dinner at the in-laws, or the riders who simply wanted a refined machine that would not frighten the livestock or the neighbourhood children. A machine refined enough to have shaft final drive like those damned clever Germans had, perhaps?

Enter BSA, who had acquired the Sunbeam title from Associated Motorcycles of Plumstead, London, during WWII – 1943 in fact – and in 1946 announced a totally new model under that famous old title. It was the work of Erling Poppe, whose background included the family business of White and Poppe, who made engines for the early Morris ‘Bullnose’ cars. He based the bike on the BMW R75 with basically an old BSA twin-cylinder overhead camshaft car power unit adapted to fit. It was a refreshing change to see a major manufacturer produce a model that was not an uprated version of a proven 30s machine, but the early production models vibrated badly and didn’t handle too well. In fact, a batch sent to South Africa for escort duty on a Royal visit were returned as unrideable, which concentrated the corporate mind rather rapidly.

Redesign

Redesign

A 1948 redesign saw the engine effectively rubber mounted, with sandwich mountings at front and rear, and rubber snubbers on the front through-bolt mountings, thus insulating the rider. The exhaust pipe had a flexible section just before meeting the silencer to absorb the movement; it was not a forerunner of Norton’s Isolastic system on the Commando, but a compromise that improved the problems of the shakes. The company had clearly run out patience with the unfortunate designer, and according to legend Poppe was given 15 minutes to clear his desk and leave the Redditch factory where the twins were built. I don’t suppose he got much of a reference, but he did find work at Douglas in Bristol.

At the Earls Court Show that year, one was presented to General Viscount Montgomery, a national hero as a soldier, the leader who turned the British fortunes in the deserts of Africa around, but never a motorcyclist; the Sunbeam disappeared into his garage and was sold to a museum after his death. Not much customer feedback there, but huge publicity for the new model and the curious crowds were so big that the stand collapsed under their weight.

In 1949 the slimmer and 25lb lighter S8 was announced, its power unit, transmission and main frame identical to the S7, but utilising BSA front forks and wheel sizes to produce a model more in keeping with general taste. It outsold the S7, but neither was a big seller before production ended in 1956.

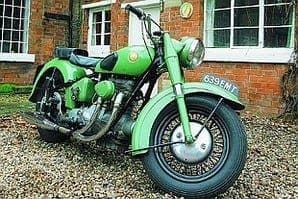

What they did do was look like a quality product, worthy flagships for the mighty BSA motorcycle division until the A10 Golden Flash proved its worth as a fast and reliable machine. The Sunbeam’s inline twin cylinder engine is an impressive lump of alloy, DTD 424 ‘Y’ alloy specification for the engineers among you, mudguarding of both versions does the job well and little touches like the road fund licence holder built into the S7’s nearside upper fork shroud suggest a motorcycle designed as a whole. The air filter Amal carburettor on the right-hand side of the inline cylinder block is hidden by an ovoid cover, and twin exhaust pipes sweep down to blend into one ahead of the flexible section in the system. Sitting at the front of the block is a 60W dynamo, mounted on the crankshaft, while on the left side of the engine the spark plugs and their HT leads are hidden behind a ribbed cast alloy cover. It is a particularly handsome, smooth motorcycle.

Achilles heel

The perceived Achilles heel of the design is the rear drive unit, where a worm and wheel are used, instead of the proven BMW hypoid type. It’s easy to blame Poppe for this decision, but BSA’s Daimler cars used worm and wheel drive units, so production of the type was already established. Was the designer persuaded to use this unit as an economic expedient? I can find no record to confirm this suggestion as fact, but it is not unreasonable speculation. It is also a long established fact of life that you blame the person who’s just left for everything that doesn’t work, so those who might have pointed Mr Poppe towards a worm and wheel unit could keep their heads down and their pensions safe.

So is the Sunbeam just another entry on the list of Great British Failures? Not if you consider the loyal following the very individual twins still enjoy and the remarkable spares service that Stewart Engineering offer to keep them up and running. And they are not as fragile as legend might suggest; I know.

I acquired an S8 and double adult sidecar in my youth; cost me all of £13, it did. The huge sidecar body was dumped and floorboards and joists from a demolition site converted the chassis into a carriage for my sprinter. That outfit was day-to-day transport, shared with my brother, who managed to dent the backside of a Routemaster with the sidecar, but it didn’t affect the outfit at all; when we briefly worked at the same place and rode home together, it was a party trick to get the sidecar wheel in the air as we turned into our street (it was actually an Avenue, being in posh Harrow) and ride past our house, do a U-turn at the next junction and ride back to stop outside our house, when the sidecar wheel would come back to Mother Earth.

It earned a brief moment of notoriety when I entered it for the sidecar class in the Ramsgate Sprint, carrying my 250 OK Supreme down there, finishing last in the sidecar class and then driving back home. But that’s a story for another day. Whatever the reputation of Sunbeam’s twins, my experience as a user was total reliability, the only downside a tendency to occasionally spit back through the Amal and set it alight. By the third time that happens, you tend not to panic.

It earned a brief moment of notoriety when I entered it for the sidecar class in the Ramsgate Sprint, carrying my 250 OK Supreme down there, finishing last in the sidecar class and then driving back home. But that’s a story for another day. Whatever the reputation of Sunbeam’s twins, my experience as a user was total reliability, the only downside a tendency to occasionally spit back through the Amal and set it alight. By the third time that happens, you tend not to panic.

So I have a healthy respect for the last motorcycle to carry the Sunbeam name, unless some fool is planning to import a range of Chinese-built lightweights and call them by that noble name. And when I met Norris Bomford on a very smart S7, and learned that it had only covered 7500 miles from new, it was too good a story to miss. Could I ride the bike and write about it? No problem, call me when you want to come over. Nice man.

Lifelong experience

Norris has a lifelong experience of motorcycles, from the D1 Bantam bought from a local farm hand to provide him with transport, through to this Sunbeam and a Japanese off-roader that gets carried on the back of the camper down to the Italian Alps for a touring holiday with a difference. His daughters, Isabel and Lucy, both ride and Lucy says she was riding a motorcycle before she could ride a pushbike; properly brought up young ladies, clearly. Lucy had a new TT100 Bonneville for her birthday recently, and found it a little too tall in the saddle. Norris called Hagon Products in Essex, where Martin H gave him precise details to measure how low the back end could come without compromising clearance, then wanted details like the rider’s body weight and leg measurement. “I phoned all the information back and they delivered two custom made rear suspension units at 8.30 the next day. Wonderful service,” he enthuses.

The Bomford enthusiasm for motorcycles is well established in the blood. Back in 1963 Norris decided to ride forth and see Europe. With tent and provisions on the back, his route from Calais took him down through eastern France across the Alps into Italy and then west to Monaco before heading back home. 2800 miles in three weeks was no mean feat of riding, but this was on a 150cc LE Velocette, the original underpowered version! Believe it or not, he did some of the off-road routes among the mountains, on one occasion running out of power in first gear and hopping off to walk along with the struggling little Velocette to reach the top.

Norris has the sorry remains of an LE or two in the shed and is looking out for a decent 200cc version.

He had long fancied a Sunbeam twin, particularly the solid looking S7, and mentioned his quest to a chap he met at a party. That was Ken Rose, long time bike enthusiast, who suggested that Norris might like to buy the one he’d had for years and wasn’t using; so many years in fact, that I rode and wrote about the bike in MCN back in the 80s. Hello, old friend.

Ken had restored the bike, but I hadn’t remembered it having such a low mileage. Apparently an earlier owner had taken it with him when he was posted out to Borneo, where the opportunities for touring on a large motorcycle are rather limited. Hence very little use, and the speedo was showing just over 7600 when we met again.

“Errrr, are those the original tyres, Norris?” I asked. “Don’t know,” was the answer, but the tread patterns did look very much like the 16in wear of the 50s. On a very blustery day, with a gale making its uninterrupted way across the Vale of Evesham and not inclined to bypass anyone silly enough to go out on a 54-year-old motorcycle on roads patchily wet, those fat rubber boots didn’t look inviting. “You’ll find it goes pretty well, and I’ve cruised it at 65mph,” explained Norris as he kicked it into deep-throated life.

The S7 is a beefy motorcycle to sit on, its cantilever single seat offering a wide and comfortable cushion complemented by wide handlebars. But its seat height of 30.5in (that’s 775mm for those of a metric persuasion) makes it feel compact and unthreatening, and sure enough it feels a lot lighter than its official dry weight of 430lb once it moves off. The car-type clutch is very light to operate and the gear change is silent and certain if you tread the ratios through with the care an engine-speed clutch suggests. Someone brought up on a BMW of the 60s or 70s would find this gearbox a revelation, light and easy to live with, and none of the stuffy “You have to learn to change gear properly on a BeeEm” nonsense that was once the accepted excuse from devotees of the Bavarian twin.

The S7 is a beefy motorcycle to sit on, its cantilever single seat offering a wide and comfortable cushion complemented by wide handlebars. But its seat height of 30.5in (that’s 775mm for those of a metric persuasion) makes it feel compact and unthreatening, and sure enough it feels a lot lighter than its official dry weight of 430lb once it moves off. The car-type clutch is very light to operate and the gear change is silent and certain if you tread the ratios through with the care an engine-speed clutch suggests. Someone brought up on a BMW of the 60s or 70s would find this gearbox a revelation, light and easy to live with, and none of the stuffy “You have to learn to change gear properly on a BeeEm” nonsense that was once the accepted excuse from devotees of the Bavarian twin.

I’ll confess to a nagging concern about those tyres, but can’t blame them for a slightly skittish feeling about the bike, the extremely windy conditions were more probably the reason for it moving about at speeds above 45mph. The performance is modest by the standards of most 500cc British twins, but the S7 moved down the road with a dignified exhaust note, no vibration that I could feel, and it would whistle up to 60ish mph without effort. I’d put the performance roughly on a par with a good Triumph 3TA, or slightly higher – maybe a match for a Tiger 90? Which was fine for the less hurried rider of the 50s, who didn’t want to race or turn heads with an impression of a racer – he wanted comfortable transport and minimal fuss or show, which the S7 delivers to this day.

Real surprise

The gearbox was a real surprise for an engine-speed clutch unit, its operation light and certain, and able to snick between ratios without effort. I used to ride an R60/7 BMW and the gearbox never measured up to this ease of operation and rider friendliness, whatever the bike’s many other strengths. The Sunbeam’s cornering over varied surfaces gave the lie to my misgivings about the tyres – it never moved off line, on smooth main roads or mucky lanes. Down bumpy lanes the suspension took all the rough bits I could find with smooth ease, and even over speed bumps near the Bomford home it steered straight and true as I lifted my seat from the Sunbeam’s and took them at 25 or so mph.

The brakes dealt with the bike’s 430lb and my extra fully kitted 200 with an effective ease that reminded me that those old boys who screwed BSAs and their close cousins the Sunbeams together were using good materials to well established working principles. These two were good by the standards of the day when they were made.

The S7 is a motorcycle whose quality outlasts the memory of the bad words that have been uttered about it, just as its slimmer and lighter S8 brother has. They share a tough engine that lasts well because its modest power output of 25bhp at 5800 rpm is never stretched, the component parts are all good quality and reward care with long service,and the two twins are handsome brothers, even if one did rather run to porkiness in his final form. Best of all, they remain strangely undervalued, the S7 selling at about £3500 for a decent example and the S8 for around £2700, not a lot for such a quality motorcycle with a supporting spares service few others can match.

My thanks to Norris Bomford for letting me loose on his S7 – a true gentleman who chooses to ride the gentleman’s motorcycle. ![]()