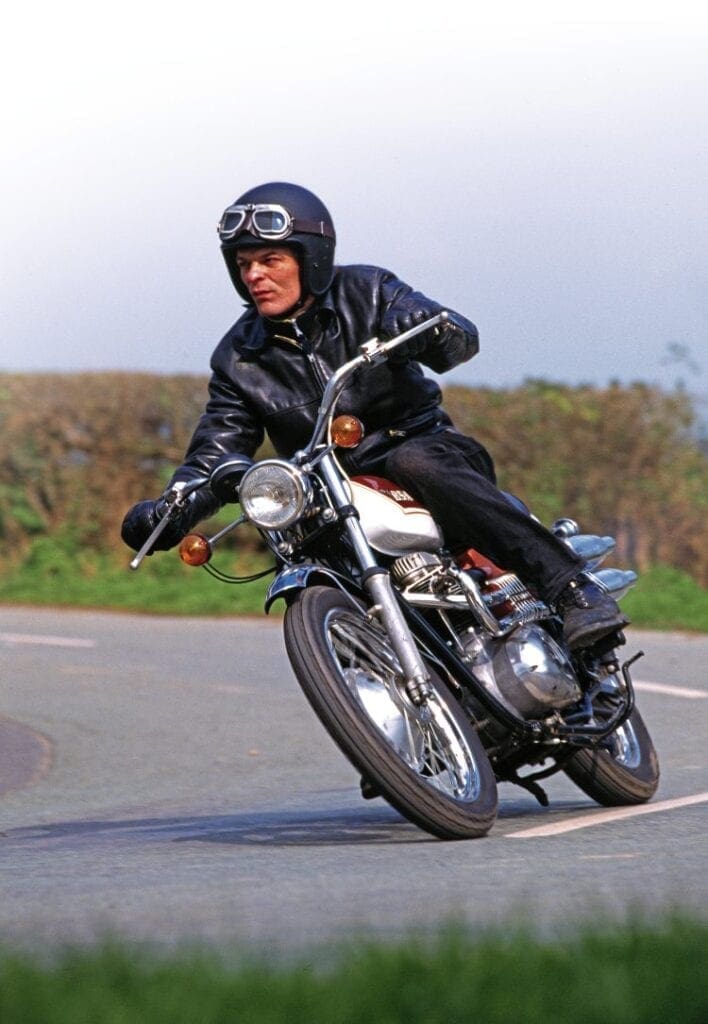

Take a tall frame, add a torquey twin engine, high bars and high pipes, and head for the countryside!

PHOTOS BY Simon Everett

Reputation is a curious thing. A great reputation – for anything – is hard to achieve and easy to lose in this cynical age, whereas a poor reputation is easy to acquire and almost impossible to lose.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

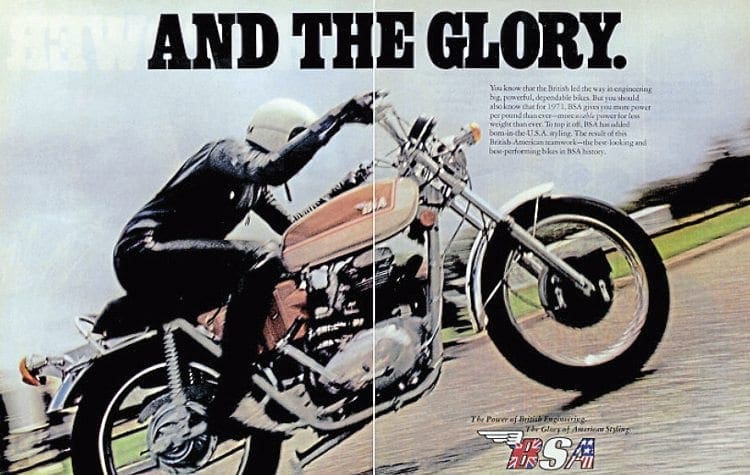

In this particular case, we’ve been pondering the strange case of BSA, of bikes built for a long time by a company which also built their greatest showroom rivals: Triumph. A curious strategy.

Even more curious was that the model ranges of the two companies overlapped in several areas, so while it would not be entirely honest nor indeed sensible to suggest that the BSA Dandy competed head-on in the buyer’s eye with Triumph’s Bonneville, or that the BSA Beagle was a threat to Triumph’s Daytona, BSA’s Bantam and Triumph’s Cub battled each other, BSA and Triumph scooters were identical bar the badging, and as the consolidating 1960s galloped in a confused way towards the consumerist 1970s, so the BSA and Triumph ranges grew ever closer.

There was nothing new about this, AJS and Matchless models had been mostly identical bar their badges for a long time, and at one point the happy punter could buy identical machines bearing AJS, Matchless and Norton badges depending on where their loyalties lay.

Which is the point, really. Through the entire history of the British bike businesses, all the manufacturers did their very best to create marque loyalty, generally by expending time, effort and money on building brand identity.

They aimed to achieve this by following several well-worn paths, ranging from idiosyncratic designs (have you ridden a BSA Dandy?) through competition, be it on track, off road or by price battles in the showrooms.

But gradually, as the years ambled by, the efficiencies of component commonality and production streamlining, along with the dribbling delight they created in the BSA Group’s bean-counting department, overwhelmed the identities of those two big names.

An ever-increasing number of parts became shared across the marques. Badge engineering sneaked in, firstly in those BSA and Triumph scooter ranges, later when blatantly BSA bangers were badged as Triumphs – was the TR25W the first of these? We should be told.

By the time the BSA Group’s motorcycle division made its last, valiant and heroically doomed attempt to leap into the 1970s, their big twin ranges were the same … apart from the engines themselves (and paint and badges; come along now, we knew that).

It’s a credit to the earlier achievements of the marques that so many riders retained their sense that the bikes were sufficiently different to justify an actual buying choice, so that the cheery, flares-wearing big twin buyers might find themselves choosing between a BSA Lightning and a Triumph Bonneville, basing their choice on… on what?

Consider, if you like, a couple of 1971 statistics. BSA’s A65L Lightning, the twin-carb sportster of the new range, developed a claimed 52bhp at 7000rpm, and used this to propel its 420lb around.

Triumph’s equivalent, the T120R Bonneville managed a claimed 50bhp at an identical 7000rpm, and weighed… the same 420lb. So according to these basic figures, the BSA would have the reputation as top dog on the 1971 Brit street scene. Did it?

No. In 1971 everyone – nearly everyone – simply knew that the Triumph was faster. Even though in fact it was not. That’s the power of a brand identity.

And while BSA and Triumph waged a profitless and pointless battle among themselves, a certain Japanese rival was offering four-cylinder machines with overhead cams and electric starts and disc brakes, which was a war being lost while irrelevant battles continued until the end.

Meanwhile… as their model ranges grew ever closer, both BSA and Triumph offered ‘street scrambler’ twins, based around their road bikes.

Triumph’s was the TR6C Trophy 650, BSA’s the luxuriously-named A65FS Firebird Scrambler, and by the time the noted oily frames arrived for the 1971 model year, the quivering punter could be excused for believing that both BSA and Triumph had followed the same ponderously unimaginative style book for both of their street scramblers.

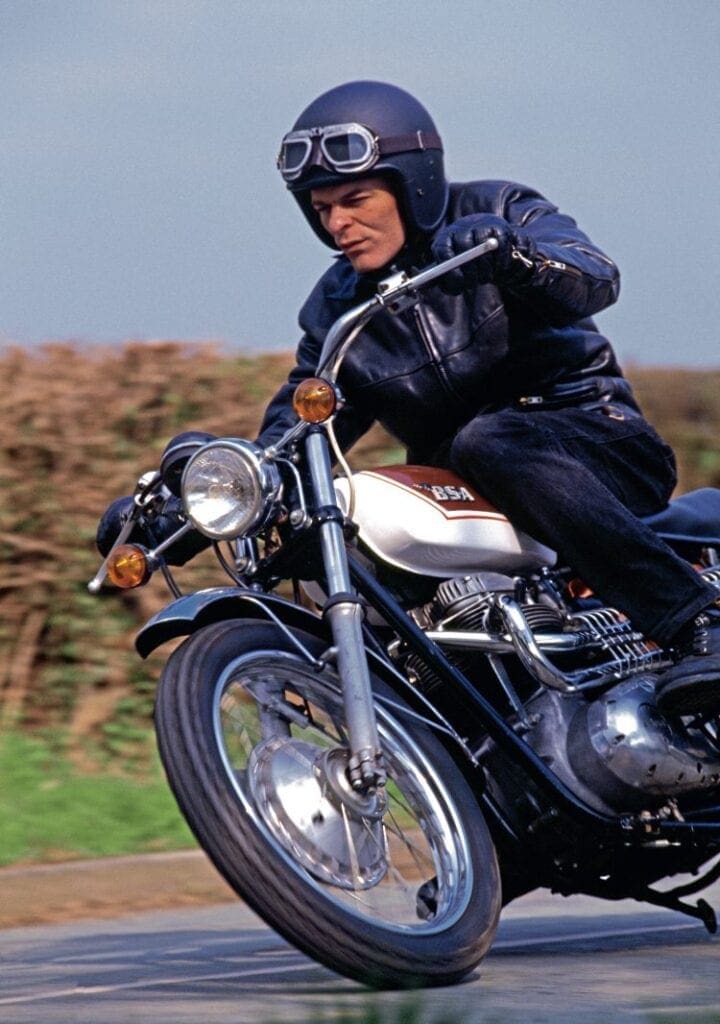

You know the style book and its chapter for off-road success (but only in the salesroom)? That’s right: take the basic engine/bicycle package, add folding footrests, high-level exhausts, maybe a smaller fuel tank and probably a smaller headlamp from the Lucas range, and the obligatory high and wide handlebars.

Say hello, then, to BSA’s A65FS Firebird Scrambler and Triumph’s TR6C Trophy.

There was one subtle and almost unremarked difference between these superficially so similar machines.

While Triumph fitted their TR6C with a single Amal Concentric instead of the pair on the Bonneville, reducing the engine’s claimed output from the T120R’s 50bhp to the TR6C’s 40 – which is a lot – BSA retained both carbs and also advanced the ignition timing of their A65FS (from 28º to 34º), raising the engine’s claimed output from the Lightning’s 52bhp at 7000rpm to 54bhp at 7250. Not a huge lot, but certainly enough to make riding the Firebird a lively experience. Which it is.

And we recommend it.

When launched, BSA’s P39 oil-bearing bicycle was roundly criticised for being too tall. Whether that’s a fact and whether it bothers you, the rider, are interesting additions to those complaints.

Certainly anyone used to riding more recent trail bikes – which was the market BSA were aiming at with the Firebird – is unlikely to be fazed by hopping up onto the seat of the BSA.

And as well as being theoretically too tall, it is also in fact quite slender.

The trim, slim fuel tank helps a lot in this, as it reinforces the impression – from the saddle if nowhere else – that this is not a massive motorcycle. Less useful are the housings for the air filters, which can bruise the thighs of any rider who enjoy getting along a little.

Taking a stroll around the machine reveals lots about it. Stand next to it and observe where the seat top is in relation to your own legs. Then take a look at the footrest positions, followed by the final observation – where do the bars place your hands.

Not every proud owner is sufficiently relaxed with life to allow just anyone to go bouncy-bounce in their P&J, but you can get a decent idea of where your hands, feet and backside are going to be in relation to each other. Now contemplate the Firebird’s exhausts…

Production engineering can be a wonderful thing, and these last BSAs demonstrate that BSA tried very hard. The previous Firebird Scrambler had arrived in 1968, intended for the US market, and was essentially a Hornet with lights – the Hornet also being a 650 twin intended for the US market and intended for actual competition.

Which must have been entertaining for the onlooker as well as for the rider, BSA twins not being famously lightweight.

There’s no space here to list all the various BSA model names and designations and their spec changes by year, but essentially, the route to the final Firebird went like this. BSA had a fast roadster twin, the Lightning (the faster-still roadster was the Spitfire, but let us not go there…) and decided to offer it as an off-road sports bike for their huge US market. This was a sensible thing to do.

So, gripped by high-tech developmental fervour, BSA threw away the lights (no sane person races in the Arizona desert at night), the silencers (making a lot of noise is not a problem in an Arizona desert) and announced their new machine to a startled world. Thus appeared the BSA A65H Hornet.

A year later, those high-tech developers set to with their stripped-down Hornet racer and added lights and silencers – such was the wild and wacky world of the 1960s, and that wackiness also produced a new name for the Hornet. The Firebird.

The Firebird Scrambler we’re admiring in these pages followed at the end of 1970, when it retained all the off-road style of its previous incarnation but gained the new oil-bearing bicycle along with the other BSA twins.

And it didn’t last very long, disappearing from the range by the time BSA’s grim 1972 rolled around.

BSA had done a lot of work on their twin engine, endlessly fiddling with the details in an unending quest for more power and less vibration.

They really needed a new engine by the time our Firebird was built, but decided to hang onto the old engine and replace the rest of the bike instead.

It’s generally accepted that there was nothing really wrong with BSA’s duplex frame and plenty wrong with the engine, especially when it was held up against the new machinery appearing from the Far East.

However, that’s what happened, and the final sporting twin from Small Heath is the one you see before you, pretty much.

Before we talk about riding it, let me explain why I talked a little about the Firebird’s history. In reality, the bike is hardly more than a common or garden shed Lightning. It has slightly more power and a few – very few – different components. Now go and find one to buy.

The price premium can be remarkable.

Whoever placed the ignition switch in the bike’s side panel rather than between the clocks deserves a thump. Remember that when well worn these simple keys can simply fall out of their switch. Turn on the fuel and ask the owner whether the carbs need tickling for a cold start. Some do, others do not.

Do whatever the owner suggests. Free the clutch by pulling in the handlebar lever and kicking over the engine until the clutch disengages.

You will be able to observe this as your right shin gouges itself into the right-hand footrest.

Find compression, switch on and kick. Do this with grit and determination, because the ignition is running a fair degree of advance and a feeble weedy prod can produce a decently vigorous kickback.

If this happens, you can ease your unhappiness by reminding yourself that this same kickback is what destroys starter motor sprag clutches. Did that help? Thought not.

Kick again, this time with power and delight as Mr Lucas’s healthy coils ignite Mr Amal’s mixture and there’s a decently deep booming from below and behind your left buttock.

The Firebird used the silencers from the earlier roadster BSAs, rather than the bogus megaphonic offerings on the rest of the oily-frame twins, and they sound fine. A really good noise. The last of the 650 engines should be mechanically quiet, too, and don’t smoke and do not leak oil.

Yes, you read that correctly. For what turned out to be their last serious development work on the A65, BSA increased the size of the jointing surfaces around their engine, as well as installing a better oil pump and, significantly, altering the spacing and the diameter of the cylinder barrel’s retaining studs, from 5/16” to 3/8”, which would suggest that the last barrels cannot be used on the earlier twins. Whatever, the mods worked.

The reputation of Triumph’s twin engine always overshadowed that of the BSA equivalents, which with the traditional benefits of hindsight appears a little odd.

More so after the redesign from the older separate engine and gearboxes to the more sensible unitised idea, where the engine and gearbox internals share the same castings.

Whereas Triumph carried on with their complicated and leaky top end design from the pre-unit engines to the unit design (and indeed all the way to the last twitches in 1988), BSA took the opportunity to design out the A10’s own separate rockerboxes, introducing instead a more sensible arrangement with the rockers mounting in pillars cast into the head itself, so the forces involved in valve operation were carried by the substantial alloy casting of the head rather than by the large collection of small fasteners which hold the rockerboxes to the head in the earlier design.

The cover over the rockers was just that, a cover, a lid, and as it has wide flat joint faces and is entirely unstressed there should be no top end leaks. When there in fact are top end leaks on an A65 or A50, they are always owner-inflicted.

BSA also produced a completely new appearance for their unit engines, again unlike Triumph. They abandoned the typically 1940s ‘bitty’ styling of the A10 engine and followed the trend set by their unit-construction singles, which were commendably neat and compact from the first C15 to the last B50. Ditching the magneto and dynamo and their drive mechanisms allowed a very smooth arrangement, which you either like or you don’t. They’re certainly easy to clean…

The BSA design used a single camshaft to operate all four valves, running four long pushrods up through a tunnel behind and in between the cylinders. Unlike their archrivals at Triumph, BSA twins avoided the fiddly and leak-prone external pushrod tubes.

If this engine has a design flaw, it’s supposed to be the timing side main bearing, which is a bush, rather than the heavier ball or roller bearings favoured by other manufacturers.

Although the bearing is seen as a weakness, and a clever modification is readily available to replace the bush with a combination ball and needle roller bearing, for most uses the original bush is fine.

The bush also delivers oil to the crank’s bearings, so frequently changing the oil and using a decent grade of oil are both good ideas – but that applies to all engines.

Drive is taken by a triplex chain through a completely conventional clutch to a four-speed gearbox, and thence to the rear wheel. All good simple fun, and capable of seriously high mileages. Electrics?

Lucas 12V alternator-driven battery, which supplies DC for the coils and lights. All conventional, robust, reliable and easily upgraded as is the modern way. Robust and reliable … those are probably the best of the many BSA attributes, as riding the Firebird reminds us.

So you’re sitting there, having remembered all about the engine that’s thrashing away between your knees. It’s time to remind yourself that the gear lever’s on the right, unlike the clutch lever which is on the left. Pull in the latter, and press down on the former.

If the primary chain is well-lubed and adjusted, and if you did indeed remember to free off the clutch before firing up the engine, first gear should engage with just a tiny degree of mechanical positivity. OK. There’ll be a crunch, almost inevitably, although that should disappear once everything’s warm and the oils have circulated.

The ratios are the same as those used on the A65L Lightning, so first is reasonably high, not entirely a ratio intended for ruts and mud, especially if the twin-carb twin’s carbs are badly adjusted, and in combination with the ignition’s advance this should make the bike a pig on the slow, nadgery wet stuff … but it doesn’t.

In fact the Firebird rides very well, and the allegedly tall chassis is very well balanced, and the folding footrests are not a worry – delicate they ain’t, to quote a BSA slogan of the time, so standing up to balance is both easy and secure.

However, you wouldn’t be buying a Firebird Scrambler to ride in trials; the machine is a street scrambler, and oddly enough it’s a very good one. The engine pulls like a winch, loads of typical BSA torque and with a scary willingness to rev hard – another result of that ignition advance and the twin carbs.

It does vibrate – it would be a miracle if it didn’t – but nowhere near as badly as reputation has it, and if your nerves are strong you can power through the 5500rpm hammers and be surprised when things smooth out again. And once more perception is remarkable.

The engine smooths over 6000rpm, but by this point the blast from the silencers and the considerable thrash and chatter from the engine will convince you that all isn’t well down below, so you ease off.

Many riders we’ve known assure us that the engine is safe well above the 7250rpm peak power point, but we’ll take their word for that.

Gearshifts are good and clean, and top – fourth – is a great A-road ratio. Once selected it has a wide speed range, easily from 40 to 80+, which is enough for most of us.

The brakes. The conical hubs are once again beloved targets of the many mockers. They work. Use a high quality cable up front and fit the longer levers if you can find them. And read the instructions… The rear sls drum is rod operated and works unremarkably well.

The riding position is… stretched out. This is not a compact bike, like a UK spec Thunderbolt, for example, and by the time you’ve hit 80 you are really feeling the pressure. Wind pressure as well as that inspired by the nagging idea of imminent engine rebuilds ahead.

The seat is comfortable, the rests set forward while the hands are rearward and wide apart.

You will always be aware of the twin black-hot exhausts close to your left leg, but the heat is only really noticeable in traffic, when you can roast a bit – a bit more if the pipes are bad copies with the bends in the wrong places or if the fish-fryer heatshield is missing.

Some riders of the time complained that the front brake and clutch levers require too long a reach, but that’s a subjective thing, and if you struggle, there are lots of decent aftermarket doglegs around to replace the shapely Lucas alloy originals.

Exactly why Triumph’s 650 twins have retained their rep for being faster, better than their BSA cousins is down to loyalties and great marketing.

If you want the same performance backed by a badge which is a little unconventional… ride a Firebird. However… they’re rare, and were listed in this form for only a year, with almost all of them being supplied to happy riders in the USA. If you find one… fly with it!

Read more News and Features online at www.classicbikeguide.com and in the latest issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!