Scorned, derided and mocked; little polarises opinion like an RE5.

Motorcycle history has never been kind to the losers and never more so than in the case of Suzuki’s oft reviled RE5. It was met with initial enthusiasm then furrowed brows before being written off as the late-20th century’s largest two-wheeled white elephant. And the 21st century hasn’t been any more charitable to the world’s most populous Wankel-engined motorcycle either.

With the advent of the internet, forums and social media have allowed countless keyboard warriors to further sully the bike’s reputation. Those with little or no knowledge have effectively dug the bike’s grave, thrown the keys on the coffin lid, then concreted over the tomb. But was the RE5 really that bad? Read on and judge for yourself.

THE BIKE

It really should be mandatory for every motorcycle rider to sample a rotary engined machine. It’s not until you’ve done some miles on one that you can genuinely see why Suzuki’s bosses committed to buying a licence from NSU and Dr Felix Wankel. That delicious surge of creamy power, the apparently unburstable nature of the engine and the unbelievably smooth ride are enough to sucker anyone into signing the deal; well in 1975 at least.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

We judge the Suzuki RE5 as a lemon of epic proportions today, assign novelty status to the Hercules (nee DKW) W2000 and brush off the various Norton rotaries as simply good old British eccentricity. Yet back in the 1960s no one really knew where the automotive industry was going. There were precious few computers mulling over theoretical options, two-strokes supposedly still had potential and many reckoned the overhead cam, four pot, four-stroke motor to be the apogee of engine technology.

And then along came Herr Wankel with an engine concept that seemed to be the answer to every automotive engineer’s dream…a true rotary engine and not just some wierd multi-piston-engined power unit built in a circle.

He had been dreaming of his engine since the dying days of the Second World War and his logic was flawless.

Instead of having pistons that had to be accelerated, decelerated, stopped and re-accelerated why not have something that never stopped moving? Surely this form of quasi-perpetual motion would be more efficient? It seemed to offer something truly unique and from 1958 through to 1973 some 26 major automotive firms supported the concept courtesy of buying licences and/or technology.

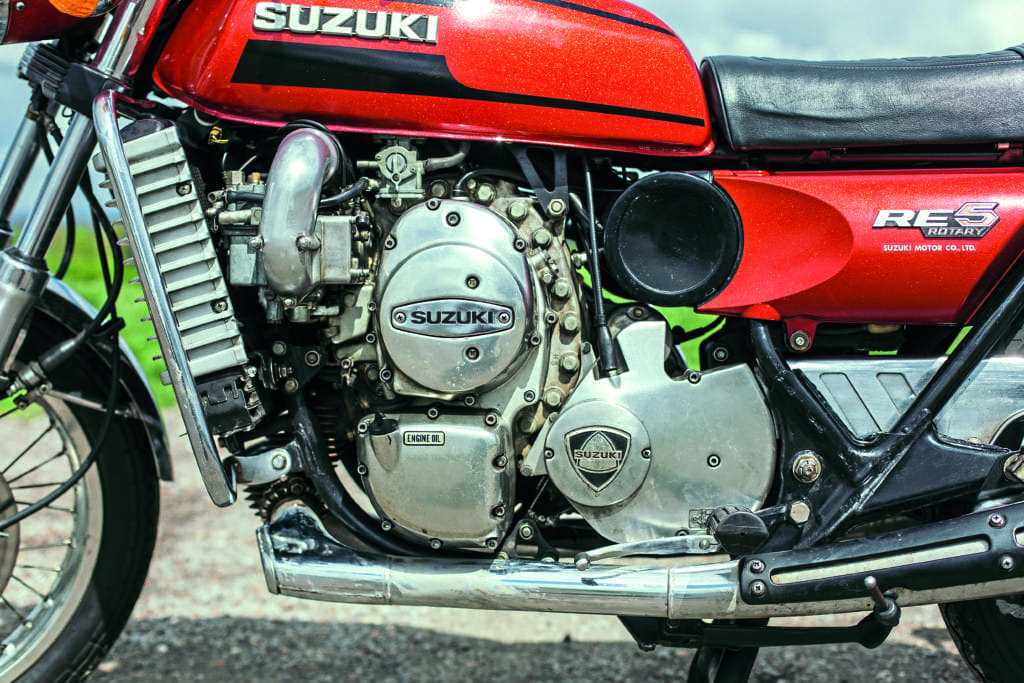

Suzuki obtained its licence in November 1970 and immediately invested in a raft of new technologies, ranging from scanning electron-microscopes for advanced metallurgy through to cutting-edge electro-plating for the engine’s combustion chamber. It’s supremely easy now to scoff at the manifest failures of the Wankel engine, but from the late-1960s through to the early-1970s that triangular rotor housed inside the almost oval engine case seemed to promise limitless options.

The future was no longer in reciprocating circular pistons, it lay with odd-shaped components describing a contorted figure of eight gyratory dance. For any company with a love and passion of engineering the Wankel engine was a delight. No cams, no valves, no push rods and no reciprocating masses – in all honesty what was there not to like and especially so when applied to a motorcycle?

So why did Suzuki take the plunge when their competitors didn’t? Well, in truth Yamaha fashioned the sharp-looking RZ201 prototype and Kawasaki played with its own – the X99 RCE. Honda supposedly weren’t interested but who can be sure the mighty ‘H’ didn’t just knock a Wankel engine up in one of their secret test facilities?

Suzuki’s engineers were both skilled and ambitious. They’d already mastered two strokes via MZ and its top rider cum development engineer and were hungry for more. Suzuki had set its sights on out Honda-ing Honda; this much was clear by the launching of their answer to the seminal CB750 in the guise of the GT750 – Suzuki were aiming high and big here.

Through the early-1970s Suzuki’s top brains were working on how to apply Japanese knowhow and dedication to the acknowledged foibles and eccentricities of Dr Wankel’s brainchild. And by 1974 they were confident they’d got it sussed.

There was huge kudos to be had from launching something so technologically different to their rivals and, unquestionably, this must have some impact upon the decision making process. Even in the late-1960s it was evident the Wankel engine was not without its issues. It produced prodigious amounts of heat, could be desperately prone to both rotor tip and side seal wear, yet Suzuki weren’t to be put off. The company even registered patents on some of the technologies it had developed in its strivings to make the concept work. It was still relatively early days for the rotary engine and no one had genuinely comprehended the inherent flaw of Dr Wankel’s combustion chamber.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

The long, thin, almost rectangular space promoted backfiring, overheating and smoky exhaust fumes yet, as with any new technology, there would always be teething troubles. Suzuki’s successive trial engines and prototypes had gradually overcome most of the major obstacles, and the company felt they really had something unique and special to offer the world of motorcycling. But why were they so confident of such new technology?

Suzuki had been looking at alternatives to the reciprocating piston engine in various guises for almost a decade so although this was ‘all new’ to everyone else it was simply the logical culmination of years of work for the factory.

Suzuki was keen for the bike to make headlines, but were also wary of scaring potential buyers off by being too radical in terms of styling yet, arguably, hedonism won out. Supposedly with input from Italian car stylist Giorgetto Giugiaro, Suzuki made massive capital of the rotary concept. The bike was graced with unique spherical indicators, cylindrical headlight casing, a tubular profile rear light and an outrageous similarly shaped instrument binnacle that magically opened up when the ignition was energised.

Side panels were scalloped ahead of a circular satin black pressings over the air filter. Recognising that this probably more than enough the rest of the bike was as conventional as possible; after all it was one thing to launch a revolutionary (sic) bike but something entirely different to alienate your potential customer base.

The bike had a suggestion of the company’s flagship GT750 about it with the radiator, tank, guards and seat, thereby arguably sufficient to get ‘buy-in’ from owners. When first shown to the public, some journalists questioned why Suzuki had chosen to fit satin black shielding to the silencers. History doesn’t record the official answer at the time, but the real reason was one of overt pragmatism.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

The outer skins of the chrome pressings became so hot in use that the manufacturers were scared witless pillion passengers would seriously burn their legs such was the heat output from the engine. In the key USA market no one wanted to be dealing with product liability law suits from the off!

When the bike was handed over to journalists the overriding feedback was positive. The inherent smoothness of the power unit, allied to a quality gearbox, immediately found favour, and it just kept on getting better. Everyone who rode an RE5 came away raving about the way the bike handled. It had been an assumption or forgone conclusion by all and sundry that the chassis was just going to be a warmed-over and tweaked version of the GT750, but how wrong they were!

Almost unheard of at the time the designers had put almost as much effort into the bike’s running gear as the engine. Suzuki was betting the farm on the RE5, and it appeared like their gamble had paid off. Folk were raving about the bike’s road manners and even suggesting it was the best handling bike to come out of a Japanese factory. Truth be told Suzuki had indeed put a lot of effort into the frame design and the suspension. The apparently quirky upright rear shock absorbers weren’t hung that way just to get attention; it was the only option the chassis team had found of taming drive chain backlash, effecting the swing arm when the bike’s throttle was shut.

So if the RE5’s launch and subsequent road tests were so gushingly positive what went so horrendously wrong? Crucially the bike was launched just at the end of the 1970s’ oil crisis, which saw supplies rationed in some places and significant increases in the cost of petrol at the pump. In the USA, where petrol was cheap(er), low 30s mpg fuel consumption from a bike with performance similar to a 500/4 was hardly good news. Even allowing for the discrepancies between US and Imperial gallons 35-37 mpg in Blighty was hardly something to shout about. The bike’s all-up weight of just over a quarter of a tonne didn’t win it many friends and with a top speed of just 110mph it wasn’t exactly a rocket ship either.

All of this, a few hugely overplayed rotor failures swiftly sorted under warranty and the phenomenal heat given off from the bike, saw minimal units shifted off the showroom floors. Global sales figures are variously said to be between 6,000 to 10,000 RE5s, which was chicken feed back then.

Suzuki were stung hard by the bike’s abrupt fall from grace and abandoned any further development. It’s been rumoured the RE5 was a total embarrassment to the firm and the entire stock of spares along with unsold machines was dropped into seas off the Japanese coast such was the loss of faith. Whether by luck or judgement Suzuki fortuitously had a Plan B.

Subsidiary funding had gone into designing the company’s first four strokes for two decades, and the resultant GS750 four and GS400 twin saved the firm from almost certain financial disaster.

Had circumstances been different, with no oil crisis, there’s a good chance Suzuki would have been able to refine and hone the Wankel concept. With more development it’s entirely feasible the RE5 would have been the progenitor of a whole family of rotary engined motorcycles.

Still cynical as to the validity of that last statement? Beg, steal or borrow to get a ride on an RE5 and tell me it’s not impressive, known faults excepted. And now get this…compatriots Mazda persevered with their Wankel engine from 1978 right through to 2012 when they finally abandoned trying to make the engine Euro 5 emissions compliant.

The Japanese are well known in the automotive world for axing lame ducks. That’s 34 years of continuous development allied to unqualified commercial success…and you still say Suzuki’s RE5 was a technological cul-de-sac?

Want to read on? Then subscribe to Classic Bike Guide and read our magazines online!