There were many fine motorcycles launched in the 1970s, but not many as widely respected as the Moto Morini 350 V-twin.

The adorable lightweight punched way above its weight when launched, and featured innovations that bigger manufacturers would not adopt for more than a decade. It was rapid rather than fast, handled and stopped as you wanted it to, looked gorgeous and was respected by most who rode one. First shown as a prototype in 1971, but not readily available in the UK until 1974, the 350 Morini was sold in both Sport and Strada versions with different levels of engine tune and trim.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

The 350 arrived after the death of the company founder Alfonso Morini, who had run the company since before the First World War. Morini was then run by his daughter Gabriella, one of the few women to run a motorcycle company. Realising that the company needed to replace an ageing range of compact singles, Gabriella Morini poached Ferrari engine designer Franco Lambertini and teamed him up with Morini chief factory general manager, Gianni Marchesini. Together the duo came up with an engine that was close to perfect for the job. Their end result was a compact 72-degree V-twin, but it was a world away from anything anyone else was producing.

The engine

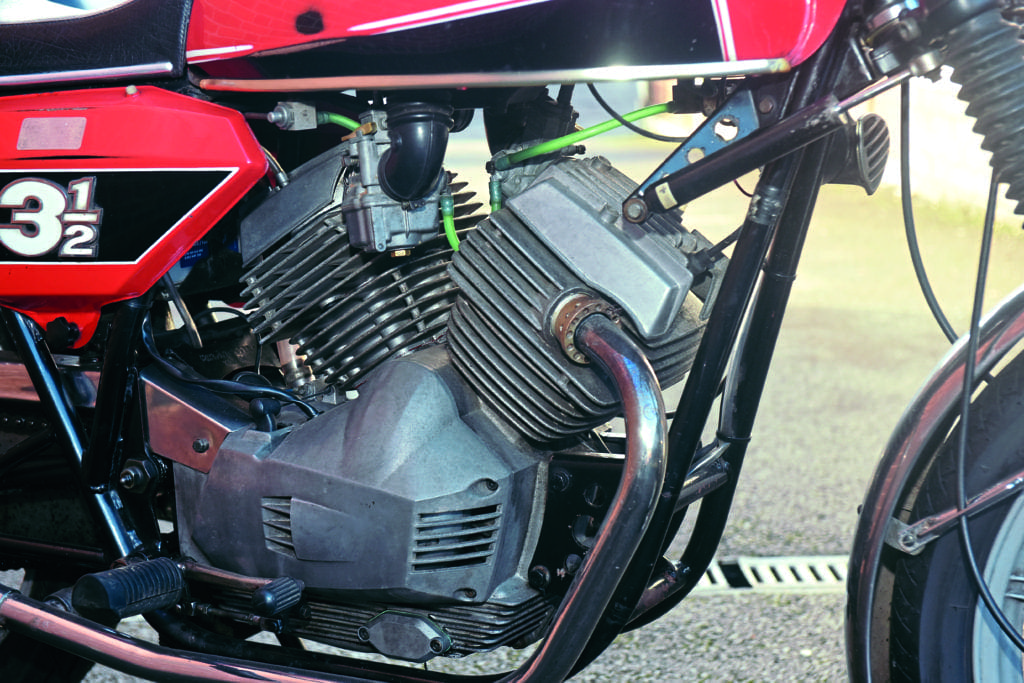

Lambertini dropped the traditional domed piston combustion chamber arrangement used by every other motorcycle manufacturer and fitted the new engine with a heron head – this puts the combustion chamber in the piston, with a flat cylinder head. The pistons were forged, and the inserts machined, while the cylinder heads were interchangeable. The heron head is commonly used in car engines and by very high-performance ones too, including Jaguar, Brabham racers and Alfa Romeo, but rarely in motorcycles; part of the reason for this is the valve operations arrangements require both valves to move up and down at 90 degrees to the piston.

This isn’t really a problem with a car engine where there will be a lot of room to play with, but on a motorcycle, this is more of an issue if you don’t want the engine to be too tall. The Morini engine’s valve gear is superbly put together, compact and simple to adjust. The valves are opened by a pair of pushrods per cylinder, the rear set fractionally shorter than the front, which are operated by a camshaft that runs between the two cylinders and is turned by a short belt – the first time a belt-driven camshaft was used in a motorcycle. Cambelts, which come in three different grades identifiable by marks on the cam pulley, need replacing every 15,000 miles or two to three years.

The flat head had another advantage, in that it was easier to fit once everything had been put together and required no special tools, which was useful as it meant the factory did not need to employ trained assembly staff in complex assembly techniques, unlike the nearby Ducati factory, which in turn made production cheaper. Morini employed several women on their engine production lines too, which in the 1970s Italy was revolutionary. In early development there were concerns the use of the heron head was going to cause combustion problems on the small engine, but with skilled development of the carb inlets and exhaust outlets the engine was largely flawless. Moto Guzzi borrowed the heron head for their V35/50 Twins later in the 1970s.

The engine has a forged one-piece crank – Morini had their own forge – with two car-type conrods using caps and shell bearings sitting alongside each other. The two cylinders are offset by 50mm, allowing the rear cylinder to get more than enough cooling air. The oil pump doesn’t send oil to the valve gear, but instead oil is sent up the pushrod tunnels by crankcase pressure, collects on the inside of the rocker covers and drips onto the valve gear from above, which requires owners to give the Morini a little while to warm up before giving the engine full throttle.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

Morini put the engine into a classically simple frame, which was a sturdy and simple double cradle with just two bends at the front, a large top tube, good bracing and near perfect geometry. Note: earlier frames are slightly different to later ones, with a kink in the down tubes on later frames.

The sport and the strada

The Sport had the higher specification and had clip-on bars, Marzocchi forks and shocks, a steering damper, alloy rims and a double-sided SLS drum front brake. There are stainless-steel mudguards, and the Sport tank has a two-colour paint job.

The ignition switch is mounted under the tank, and the Morini may be the first machine fitted with an electric fuel tap, a large solenoid-operated item with a manual reserve tap fitted on the other side.

The original seat has a groovy hump that is a considerable squeeze for a pillion, there are rearsets, a chromed CEV headlight on Grimeca brackets, and a tail-light, also seen on Ducati and Moto Guzzi models of the period. The Sport was later fitted with a chromed disc on spoked wheels, which could be doubled up as an option, and Grimeca calipers, that were more than capable of hauling the little vee to a halt. Opinions on the efficacy of the drum and disc vary. Some owners find the drum grabby, while others feel the disc isn’t quite up to the job. Often this opinion will be guided by which bike they own.

Later models had powder-coated Grimeca cast wheels. Marzocchi gas shocks with remote reservoirs are a popular aftermarket addition. There is even an electronic rev counter. The Strada was the touring or GT version, and was briefly fitted with Paoili forks before using the Sport’s Marzocchis. It had a more conventional 2LS front brake, later replaced by the single disc. The Strada has a longer and more comfortable seat, basic footpegs and traditional handlebars. For everyday use the Strada can be a better all-round motorcycle than the Sport. The riding position is much more forgiving, the fuel economy is better, and the power delivery is smoother.

Adored by magazine journalists, who would test the 350 Sport against Honda’s CB400 four or Yamaha’s RD400 and find the Japanese rivals wanting, the problem for Morini was their bikes were expensive compared to the competition – a Sport would cost £2-300 more than a Japanese 400. The Sport cost almost as much as a Norton Commando at launch and continued to be expensive. By 1979 it cost only slightly less than a Kawasaki Z650 and more than a Triumph Bonneville.

The flatslide Dell Orto carb on the front cylinder feeds the fuel in on the left, and the exhaust port is on the right, which means the cylinder and cylinder head cooling is not obstructed by an exhaust pipe. The rear cylinder head operates the other way around with the carb on the right, and the exhaust pipe is a short item covered with a heat shield running down the left-hand side, which has a balance pipe linking it with the right. The exhaust pipes are held on with castle nuts and split collets. Both carbs draw their air from a filter box mounted under the tank.

The 350 engine has a six-speed gearbox with a right-foot shift. There is a dry clutch, which was fitted partly because Lambertini decided it was sportier, but also because it was felt the oil filter, which is a wide plastic mesh item that runs across the width of the vertically split crankcases, would not cope as well with the inevitable detritus produced by a wet clutch. The Morini has a left-hand kickstart which is not as awkward to use as it first appears.

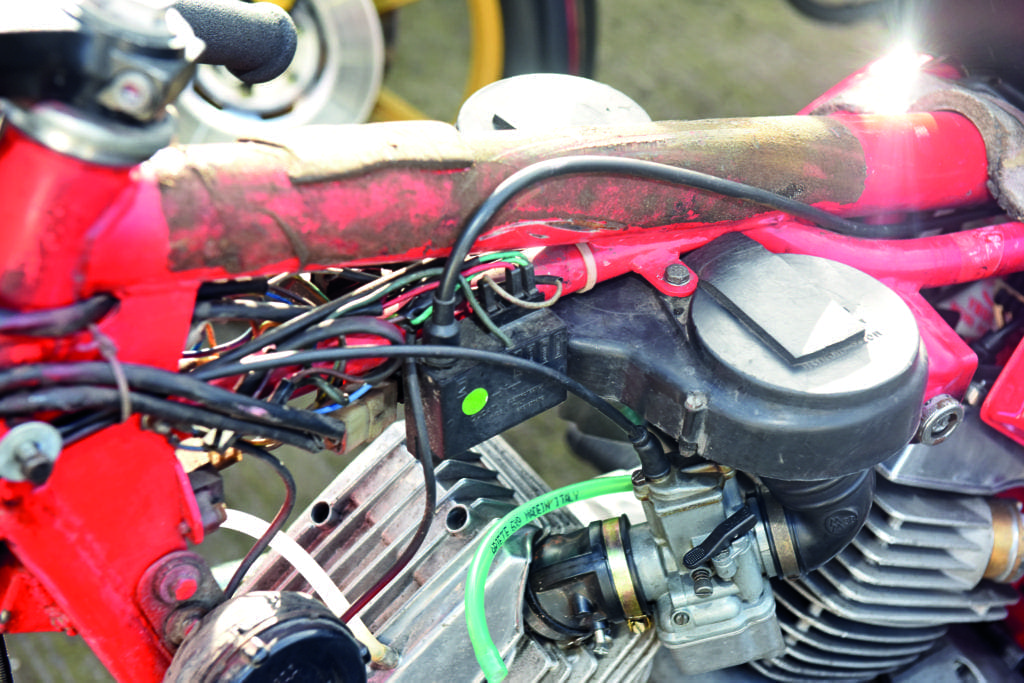

Another innovation was the use of electronic ignition, which is fired not by the battery but by a coil in the generator, so you can kickstart a Morini with a flat battery. Later models were fitted with an electric start, a large item mounted at 90 degrees to the crankshaft, which turns a short chain, which turns three bob weights, which use centrifugal force to engage with a dish on the outside of the right hand mounted generator. It wasn’t a huge success, but fortunately the kickstart is more than capable of flipping over the engine.

Despite the Italians’ much maligned reputation for poor electrics in the 1970s, the electronic ignition system is pretty good and easy to set up, the actuator mounted on the left-hand end of the camshaft. The rest of the electrical system, in particular the circuit board under the right-hand side panel, is a nightmare of electrical spaghetti.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

First shown as a prototype in 1971, but not available in the UK until 1974, the 350 Morini was sold in both Sport and Strada versions with different levels of engine tune. The Sport has a lumpier camshaft, and higher compression pistons. Some machines have had mix and matched Sport camshafts with Strada pistons fitted by owners, allegedly to provide better power delivery but more likely because of a shortage of spares in the 1980s.

By the late 70s the 350 had lost its original primitive switches, though the replacements were not up to comparison with Japanese equivalents. The tank became sleeker, side panels were extended and the seat profile on the Sport was modified for a more angular look, but remained uncomfortable two up. The wire-spoke wheels were replaced with powder-coated Grimeca cast items, brakes were now disc at the front, with a drum retained at the rear. The Strada had a plastic chain guard and painted mudguards.

The K series 350 was almost the last example of the breed, with updated looks. Later models featured 80s graphics, a small nose fairing, belly pan and a square headlight. It also had a left foot gearchange.

The engines also appeared in US custom alternatives offered when Cagiva took over the factory in the late-1980s in a complicated deal that saw them get Morini at the same time as they bought Ducati. The Excalibur and New York customs were built at the Ducati factory and their appearance, it is fair to say, splits opinions. Less controversial are the Kanguro trail bikes, which were successful uses of the engine.

The last Morini 350 was the Dart, a curious machine, almost completely enclosed in white plastic which had the engine fitted into the frame of a Cagiva 125 sports bike. It is a tribute to both the lightness and power delivery of the Morini engine and the quality of the Cagiva frame that the combination works.

Of all the 350s, the Sport is the most attractive. It has giant killing performance and very low running costs. The drum brake Sport is the most desirable one and changes hands for the most money, but the wire wheel version with the optional extra disc, made briefly from 1976/77, is a better ride if you want a machine with the bugs ironed out, brakes to go with the handling and a marginally more comfortable seat. The cast wheel disc model, made from 1978 on, is commonest and best for starting and going, with an uprated alternator. The late 70s/early 80s Strada is the easiest to live with.

Cagiva ended Morini production in the early 1990s, before the brand returned with the hand-built Corsaro 1200 v-twin in 2006. Production has stuttered since then, but it is a tribute to the affection with which the 350 is held that in its latest update to the machine, the 1200 Milano – not the Bologna, curiously – has been designed to mirror the little vee. And the Bialbero Corsa Corta 1187cc V-twin was designed by Franco Lambertini.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!