I am prejudiced. I have a deep affection for the majority of motorcycles, but don’t like BSA C10s, the Norman Nippy, Clubman’s Goldies and AJS and Matchless so-called lightweight singles; I have a prejudice against them, every one. Love the traditional Plumstead singles and had a heavyweight Matchless G80S that went all over the place in a dignified and relaxed way. But my view of the lightweights was dictated by a ride on one for an early edition of Classic Bike Guide, when an unremarkable journey across hilly Shropshire was made instantly exciting and memorable by a front brake cable nipple pulling out as I braked for a tee junction. Limping slowly home to the proud owner with only engine and rear wheel braking was not an experience to list amongst My Best Rides and I was very glad to hand the damned thing back!

So I don’t much like AMC lightweights, and remember the 250 AJS that a fellow RAC-ACU Training Scheme instructor thought was the bee’s knees – pardon that expression, but it was long ago, before dogs had whatever bits are supposed to be appealing now. I was riding my brother’s Matchless G3L at the time, a lovely heavyweight bike that I’d buy tomorrow if I knew where it is (offer subject to suitable finance being available, of course) and there was just no comparison. He’d bought it from the training scheme as they updated, and as it was run by the Sunbeam Club it had been returned to the Plumstead factory at intervals for a full service and overhaul, courtesy of the connections of Ralph Venables, legendary trials organiser and historian and not one to cross words with. I remember it coming back from its periodic factory looking-over when I was a pupil on the same scheme, and how the instructors all wanted to ride it. Frankly, such a nice bike was wasted on a succession of unsympathetic learners.

Then I went to Kettering, the Fair City of, to ride a couple of Associated Motor Cycles’ finest courtesy of Ernie Merryweather’s Northants Classic Bikes. One of them was the muscular 1966 AJS 31CSR the AJS and Matchless OC were offering as a raffle prize and the other was supposed to be a particularly fine example of AJS’s 500 twin, the Model 20. But that had been sold by the time Classic Bike Guide arrived. But the chance was missed and the affable Mr Merryweather wheeled out one of those lightweights things instead, a 1966 250cc Matchless G2CSR. Were those dark clouds on the horizon or was it just the mood set by my prejudice?

Then I went to Kettering, the Fair City of, to ride a couple of Associated Motor Cycles’ finest courtesy of Ernie Merryweather’s Northants Classic Bikes. One of them was the muscular 1966 AJS 31CSR the AJS and Matchless OC were offering as a raffle prize and the other was supposed to be a particularly fine example of AJS’s 500 twin, the Model 20. But that had been sold by the time Classic Bike Guide arrived. But the chance was missed and the affable Mr Merryweather wheeled out one of those lightweights things instead, a 1966 250cc Matchless G2CSR. Were those dark clouds on the horizon or was it just the mood set by my prejudice?

But hold on a minute. 1966 was the last year of production for the lightweights at the Associated Motor Cycles factory, and by that time AMC had given over space at its James factory in Birmingham to stock the Suzukis it was importing. Honda had made huge inroads into the commuter market with its unburstable little 50cc Cub and followed that up with 125, 250 and even 305cc twins that would outpace many traditional British bikes with a much bigger capacity. The world of motorcycles was changing very rapidly and it would be interesting to put this very neat little British single into historic context and try to assess how it measured up against the invading hordes from the Far East. This was a very well detailed example of a major manufacturer’s response to that threat, with sporty styling and a power unit uprated by a series of modifications to improve both performance and reliability.

The lightweight models were launched in 1958 for the 1959 season and in 1962 came the sporting CSR version, starting at engine number 12128, and fitted with steel instead of cast iron flywheels with a large diameter crank pin “…to allow use of the high compression piston…” as the Service and Overhaul Manual puts it. That was actually a change from 7.8 to 8.0 to 1 in 1964 and finally to an impressive 9.5 to 1 from 1965, when an uprated oil pump allowed an oil flow directly to the cam followers. If you have ambitions to modify your own power unit and it has an engine number below 12828, you’re facing a complicated job, as new crankcases are required to make the changes. Logic suggests that few owners would have gone to such expense when the bikes were relatively new, and there was a realistic chance of part exchanging the bike for something else. Not that they were very big sellers, if the advance from engine number 12128 to 12828 in six is any indication; that’s less than 120 a year, or less than three a week. So they’re rare and a good example even more so.

The lightweight models were launched in 1958 for the 1959 season and in 1962 came the sporting CSR version, starting at engine number 12128, and fitted with steel instead of cast iron flywheels with a large diameter crank pin “…to allow use of the high compression piston…” as the Service and Overhaul Manual puts it. That was actually a change from 7.8 to 8.0 to 1 in 1964 and finally to an impressive 9.5 to 1 from 1965, when an uprated oil pump allowed an oil flow directly to the cam followers. If you have ambitions to modify your own power unit and it has an engine number below 12828, you’re facing a complicated job, as new crankcases are required to make the changes. Logic suggests that few owners would have gone to such expense when the bikes were relatively new, and there was a realistic chance of part exchanging the bike for something else. Not that they were very big sellers, if the advance from engine number 12128 to 12828 in six is any indication; that’s less than 120 a year, or less than three a week. So they’re rare and a good example even more so.

It’s significant that the power unit is easily mistaken for one offering unit construction, with gearbox and engine sharing one large casting enclosure, a style the opposition were adopting at the time. The record suggests that the idea worked well for some, Triumph’s service manager John Nelson explaining that the unit models were much more reliable than their forebears, which had come with separate box and engine. Up in Birmingham, Associated Motor Cycles’ subsidiary Norton had launched the unit construction 250cc Jubilee in 1958, to be followed by 350 and 400cc versions. But in Plumstead they seemed loath to follow the new fashion, and the Lightweights actually had a separate barrel-shaped gearbox that sat inside the alloy shell that also contained the oil tank. Quite why they wanted to hide such a shapely thing as an oil tank, which could add to the bike’s looks and provide more efficient cooling when mounted externally is beyond my understanding. Then you read the specification in a little more detail and realise that the tank held only two and a half pints, which meant a modest amount of lubricant doing the double task of oiling and cooling, with little in the way of an effective heat sink. Oh dear. And the separate gearbox had a capacity of three pints, which my maths tells me is 20 per cent more than the power unit enjoys. Oh dear again. And the recommended oil change interval for the lightweight singles is 3000 miles, while for the more traditional heavyweights it’s 5000 miles. I think I’ll stop the technical appraisal right now, before my confessed prejudice becomes too obvious.

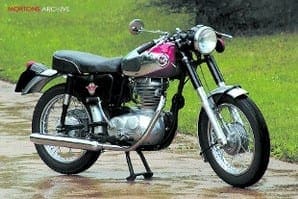

Let’s just look at this admittedly handsome little bike, compact in size but not such a tiddler that anyone more that 15 years old would feel embarrassed to be photographed on it. Its looks have a very masculine appeal and with a little imagination you can see that it would appeal to a British traditionalist if it was parked in a line-up with typical Eastern alternatives of 1966. That does not include the contemporary CZ and Jawa, where the influence of Communist solidarity with the rest of the Eastern Bloc took their worthy offerings out of the front row of appeal and parked them right up in the back of the car park.

Let’s just look at this admittedly handsome little bike, compact in size but not such a tiddler that anyone more that 15 years old would feel embarrassed to be photographed on it. Its looks have a very masculine appeal and with a little imagination you can see that it would appeal to a British traditionalist if it was parked in a line-up with typical Eastern alternatives of 1966. That does not include the contemporary CZ and Jawa, where the influence of Communist solidarity with the rest of the Eastern Bloc took their worthy offerings out of the front row of appeal and parked them right up in the back of the car park.

The smallest Matchless in that fine old company’s 1966 range came with chrome mudguards and handlebars mildly dropped to enhance a hint of sporting pretensions. Never mind the hi-tech upright stuff rivals were offering, this was a sporting 250 in the Good Olde British tradition, ideal for a raucous cruise down the North Circular Road to that bastion of tradition, the Ace Café. You could park it up there with little risk of bits being nicked, simply because it was considered a mild little thing, while serious people like Gold Star owners were at risk of coming out of the café to find their pride and joy minus its Amal GP carb. Your 250 Matchless rider would sip his coffee and walk out to find his shiny new bike untouched by the greasy hands and spanners of the local naughty boys.

Like me at Kettering, he’d turn the Wipac switch to I for Ignition after tickling the Amal carb, and with a bit of weight behind it the first kick would produce a response from the oversquare 70 x 65mm single. It did in Kettering and if prolonged efforts at the Ace didn’t get results, the owner could switch to E for Emergency and hope that would work.

Like me at Kettering, he’d turn the Wipac switch to I for Ignition after tickling the Amal carb, and with a bit of weight behind it the first kick would produce a response from the oversquare 70 x 65mm single. It did in Kettering and if prolonged efforts at the Ace didn’t get results, the owner could switch to E for Emergency and hope that would work.

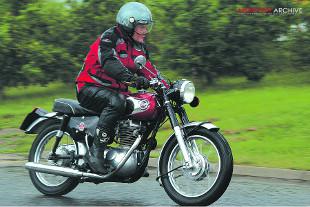

Let’s leave that unfortunate owner in the Ace Café car and lorry park, wondering where he could phone either the RAC or his mum. In those harsh, pre mobile phone days, life could be a real bitch. Quickly back to Kettering, and a particularly fine example of the G2CSR line, its motor thrapping in response to the throttle and anxious to be out on the road. Silently into first gear, feed in the light clutch and off towards the countryside we went, the 250 pulling strongly in third at a strictly legal 30mph, but not happy at that pace in top. It’s what you should expect from a sporty single with a high compression ratio, born in the days before sophisticated aids like engine management systems made singles flexible, so the little motor spun happily along in strict compliance with the law of the land. This was Northamptonshire, you understand, land of speed camera lenses.

It being well past lunch time, I stopped at Roy’s Café for a bacon sarny, attracted by the Union flag proudly displayed to make a background for this British motorcycle. Mind you, I suspect I was chewing Danish bacon as I admired the bike and then cast an eye to the sky. Oh Lordy Lord, that black cloud was obviously part of a major Rain Rally on the way to Kettering, and it seemed this would not be one of those glorious sunny afternoons wending down winding country lanes without a care in the world. And just to complete the gloom, I realised that I’d left my overtrousers at home.

It being well past lunch time, I stopped at Roy’s Café for a bacon sarny, attracted by the Union flag proudly displayed to make a background for this British motorcycle. Mind you, I suspect I was chewing Danish bacon as I admired the bike and then cast an eye to the sky. Oh Lordy Lord, that black cloud was obviously part of a major Rain Rally on the way to Kettering, and it seemed this would not be one of those glorious sunny afternoons wending down winding country lanes without a care in the world. And just to complete the gloom, I realised that I’d left my overtrousers at home.

Off I went into rural Northamptonshire, the willing Matchless picking its way through urban traffic with little effort and proving to be very flickable around roundabouts and equipped with decent brakes. The front one didn’t look like it had been borrowed from a racing model, but was just a tidy full-width hub with a seven-inch single leading shoe drum brake that worked as well as it looked. The gearbox was sweet, up and down with little physical effort and no missed gears to make the unfamiliar rider blush. And it was easy and stable to ride for the modest distance I covered, even if the mixture of tubular steel chassis and channel engine cradle is hardly based on the successful AJS and Matchless competition models’ designs. I suspect it’s typical of many modestly powered British motorcycles, that had adequate road holding for the available performance and would only be found wanting in absolute extremis. But was victory in the 250cc class of the Thruxton 500 Mile Production race a marathon of extremis, or just proof that riders like Peter Williams could take almost any unlikely motorcycle and make it sing?

I was beginning to like this little Matchless of modest performance, until those damned black clouds arrived, preceded by what started as a shower. The shower grew to rain and the rain to a full throttle downpour that had cars stopping at the roadside until the intensity of the vertical wet reduced. Common sense took over from bravado; I parked the G2 and took shelter in photographer Jim Davies’ car, hoping the extreme wet would relax a little; when a loud rattling on the roof confirmed that it was actually hail falling, a strategic decision was taken to stay in the dry. I thought of my Toucano Urbano overtrousers back home, as waterproof as any I’ve ever owned, but no good on the shelf when I was in damp and distant Northamptonshire.

When the downpour eventually eased the light was beginning to wane, so exciting action shots of the Matchless riding around the outside of cars (I wish!) were out of the question. It started first kick again, unaffected by the pouring rain and thumped back to Northants Classic Bikes to be dried out and cleaned, ready for its new owner to take it home. Because it was in fact sold, to a club member who fell for its good looks and wanted it to share space with his 650 twin. I’ll admit I was beginning to quite like the winsome little thing, with performance a little better than more popular models like BSA’s C15 but no match for Eastern invaders like Honda’s CB72 or Suzuki’s six-speed twin.

When the downpour eventually eased the light was beginning to wane, so exciting action shots of the Matchless riding around the outside of cars (I wish!) were out of the question. It started first kick again, unaffected by the pouring rain and thumped back to Northants Classic Bikes to be dried out and cleaned, ready for its new owner to take it home. Because it was in fact sold, to a club member who fell for its good looks and wanted it to share space with his 650 twin. I’ll admit I was beginning to quite like the winsome little thing, with performance a little better than more popular models like BSA’s C15 but no match for Eastern invaders like Honda’s CB72 or Suzuki’s six-speed twin.

Within a year of this G2 leaving the factory, Associated Motor Cycles had folded and the rescue of the factory had seen the range trimmed drastically, with the 250s amongst the first to be sacrificed on the alter of survival in a harsh world. Even as rarities in this classic conscious world they don’t attract a lot of support and are destined to forever play second fiddle to their more highly regarded heavyweight and old fashioned brothers. It’s rather cruel to suggest that AMC lightweights are living proof that you can’t fool all the people all the time, but that seems to be the lesson time has taught us.

I’m not as prejudiced as I was a year ago, but if you offered me a 1966 250 Ducati or Matchless, I’m afraid my patriotism still couldn’t be stretched that far. ![]()