After years in its larger brother’s shadow, the KH400 is now becoming sought-after in its own right.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

THERE ARE A few things that seem to sum up Kawasaki two-stroke triples. The buzzsaw whine and off-beat crackle from the silencers, the questionable handling, the some might say slightly deranged look of their pilots. But one of their more unusual features sits under the seat, where Kawasaki, in a rare example of a motorcycle manufacturer acknowledging its product’s weaknesses, put a small box to hold three spare spark plugs for when your current set inevitably fouled.

The triples were born in 1968 with the 500cc H1. Kawasaki had been working on Project Blue Streak, a plan for its new flagship two-stroke, since 1964. This was to provide a complement for its 250 Samurai and 350 Avenger twins, which at that point, were only just heading for production. Kawasaki chose an in-line piston-ported triple design over an enlarged version of the Avenger, partly because Yamaha and Suzuki were already building larger-capacity two-stroke twins and Kawasaki wanted to stand out. The H1 broke cover as a truly modern motorcycling creation, launched with CDI ignition, oil injection, intimidating handling and breathtaking acceleration and top speed. You could buy one in the US for two-thirds the price of a new Triumph Trident or Honda CB750 and it was faster than both, on the road or the drag strip. There was no electric start, but it was easy to kick over.

The H1 or as it was also known, the Mach III, arrived in the summer of 1968, with that fire-breathing engine wrapped in a frame of dubious design, suffering from a poorly configured swinging arm pivot made with indifferent manufacturing tolerances, skinny front forks, a powerful drum brake and a set of shock absorbers from the 250 Samurai. Handling was not top of the agenda. If you look at the frame of a Kawasaki triple with modern eyes you can see the cause of the problems. The steering head is heavily braced, but is not triangulated. The top strut heads backwards at a short, sharp angle, putting all the stress from the steering head in the middle of the top tubes right above the engine instead of further back. The frame would, inevitably, flex.

Despite, or perhaps because of, a reputation for unpredictable, hairy-chested behaviour combined with the all-conquering straight-line performance, the triple survived in the Kawasaki line-up until the early 1980s. The 500 H1 was joined by the even more bonkers ‘World’s fastest motorcycle’ the 750 H2, which was given the unedifying nickname of ‘the Widowmaker’, and they made it to 1975 before being dropped.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

In the meantime, the slightly more civilised S1 250 and S2 350 models, which were a touch smaller and just as exciting, had joined the H models on the production line. An S3 400 was added in 1974. The S3 had a rubber-mounted engine with a trio of slide carbs, a five-speed gearbox and a four-bearing crankshaft, later given two more bearings. Kawasaki had reverted to points ignition for the smaller bikes, there was a new tank which held around three gallons and fuel consumption on the S3 was rather better than the S2 350, which had used 16mpg when tested by one US magazine.

The triples were relaunched in 1976 as the KH (Kawasaki Highway) range, featuring near-identical 250 and 400 models along with a 500 using a heavily detuned and re-geared version of the H1 engine as Kawasaki tried to persuade riders it was a sports tourer. The 500 lasted a single year.

After nearly a decade in production, by 1977 the two-stroke triple was dead in the US, once its biggest market. This was partly down to the engine’s insatiable thirst for increasingly expensive fuel, partly to emissions regulations, but also because Kawasaki was having more success with its two new and rather more respectable four-stroke twins, the Nebraska-built Z400 and the newly launched Z750. These were such huge sellers there was now little interest in the triples and Europe and Japan became the two-strokes’ principal marketplaces.

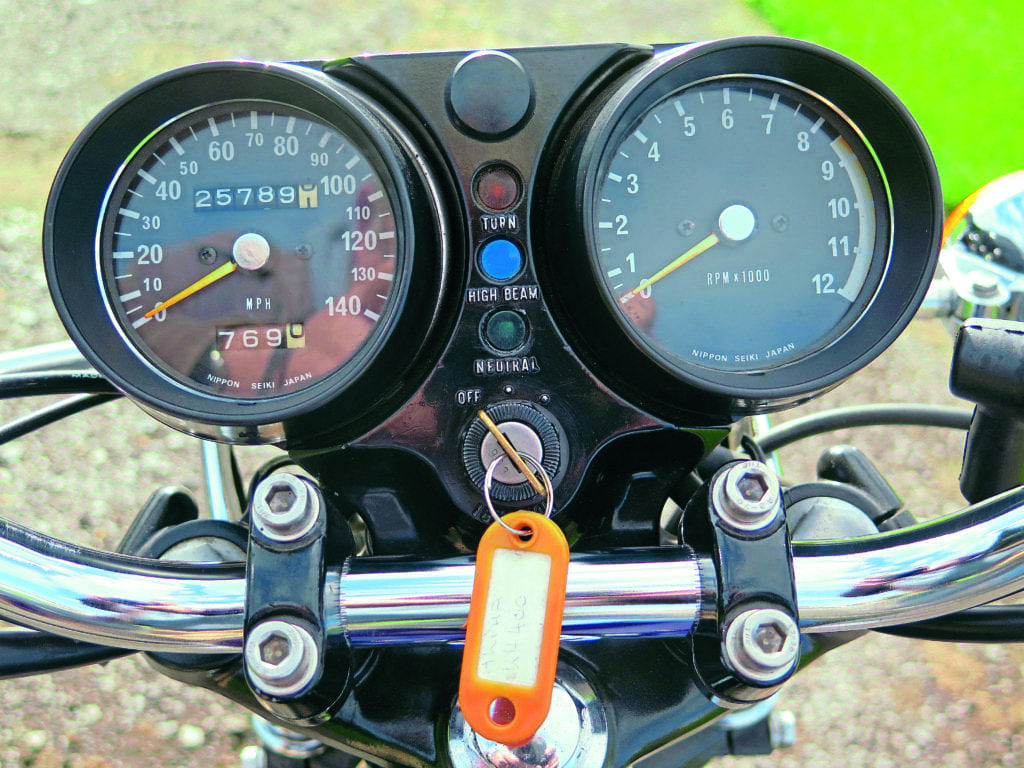

The KH400 was a larger, updated and slightly less-exciting version of the S3 400. The airbox was redesigned, the silencers made more restrictive and the carbs re-jetted, and the engine could run on unleaded petrol for the first time, producing 38bhp. The changes chopped 4bhp from the power output of the S3 and the engine was fitted with CDI ignition, a first for the smaller triples.

For more content, why don’t you like our Facebook page here, or follow us on Instagram for a snippet of our striking pictures!

The gearbox sprocket was made one tooth larger, which reduced acceleration, but by now the KH was competing with the RD400, and Kawasaki had decided that the best way to do this was to create a more civilised ride. Extra gussets were put on the frame and there was a strengthening of the shock-absorber mountings. Softer shocks were fitted, but this smoother ride came at a cost. Road tests of the time declared that the 400 did not handle as well as its predecessor, reporting that it wallowed a little on twisty roads. Two colour options were offered, green or orange.

A nine-inch disc was fitted to the front, but like many a 70s Japanese bike, this stainless item lacked bite in the wet, even on a bike as light as the KH. The reliability of the early CDI units was questionable too.

Up against the Yamaha RD400 and Honda CB400 Four, the by now ageing KH struggled, as these were both faster and handled better. The real seller for Kawasaki was the L-plate legal KH250, beloved of a certain kind of bus-shelter cowboy. The 400 was barely faster than the 250 and had only CDI ignition to justify a higher price. Hardly anyone was going to buy a KH400 when they had passed their test and some dealer discounters would sell you a new KH400 for less than a KH250. The brand loyalists were going to head straight for the Z650 or Z900. This bubble would eventually burst when learners were restricted to 125cc bikes, and one dealer would give you a KH250 if you bought a Z1300 six.

Kawasaki updated the KH400 to A4 spec in an upgrade in 1977 that consisted of a nicer paint job, and the removal of a metal strip from the seat. The bike was available in candy emerald green or candy royal purple with pinstriping.

Kawasaki is believed to have stopped making KH400s that year, but kept the model in the catalogue until 1980 in the UK in the same paint jobs. Some dealers still had models gathering dust in 1982. An A5 model was sold in Germany and Italy, which had further changes to colour schemes, German models were detuned further to 36bhp to fit in with insurance groupings. In Japan, an A6 model was offered in a striking blue finish or with a green paint job; a tribute to racer Kork Ballington. Kawasaki in the UK did the same thing with the KH250 and the later Z250 four-stroke twin.

Despite the long decline in sales, the Kawasaki triple has a dedicated following. As not everybody can afford to buy, to run, or to risk life and limb on a H1 or H2 the KH400 has experienced something of a comeback. Fast and flashy is what’s going on here, and with the current fashion for all things 70s and two-stroke, a motorcycle that was once in the bargain bin has seen its value racing ahead like the pilot of an H2 on an LA freeway.

Upgraded componentry is fairly easy to come by and a well sorted KH can do impressive things. There’s a small but incredibly keen Kawasaki Triples Club that meets ups several times a year. One thing to check for if interested in buying a KH400 is to make sure it really is a KH400. Lots of KH250s ended up with KH400 engines in them. It’s easy to spot from the frame number, but it’s worth looking out for.

KH prices are keeping pace with the S models which are generally a little more expensive. You should be able to find a good KH400 for between £4,000 and £5,000. Imports and shed finds in various states start at £1,500 and while a bike this cheap will be likely to require serious work the simplicity of the design means they aren’t beyond the skills of the average home restorer.