Winter wanderer

No great shakes as a superbike, Enfield’s 700 is instead an oddly competent practical classic

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

PHOTOS BY Rowena Hoseason

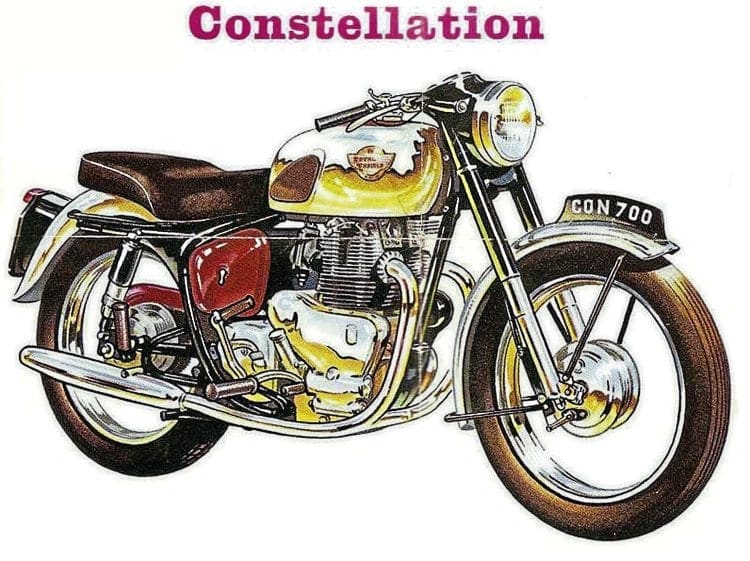

WHEN ROYAL ENFIELD launched the Constellation in 1958, it unequivocally aimed its new 692cc superstar – the biggest parallel twin on the market – at the performance end of that market.

The Connie’s cosmetics were liberally sprinkled with stardust, from the shimmering chrome on the petrol tank and cut-down mudguards, to the sports-style flat bars, siamese pipes and minimal chainguard.

Superficially, the Constellation had come a very long way from its Meteor origins.

Enfield’s mammoths were all built at Bradford on Avon rather than Redditch, and the first of the big beasts was trumpeted in 1953.

But while its capacity sidestepped the competition, who were developing their 500 twins into 600s, (sometimes even daring to go as far as 650cc) the 36bhp, 405lb Meteor was no fire-breathing speed freak.

Instead, it was a throwback to the prewar world of family motorcycling in which big twins (more usually with their cylinders arranged in a V) lumbered in leisurely fashion about the landscape.

Indeed, the Meteor was once wonderfully described by Bob Currie as “a rather woolly animal intended primarily for sidecar haulage.”

When the next incarnation, the 40bhp Super Meteor, was introduced in 1955, it succeeded in travelling at 100mph yet somehow did not explode in a shower of incandescent enthusiasm.

This accomplishment encouraged Enfield to go the whole hog.

To push envelopes. To over-egg the pudding. To take a design which had started out as a clever combination of 350 single and 500 twin technology – with a chassis that had originally been intended for a sprightly 325lb lightweight – beyond its reasonable operating tolerances.

And in 1958 it launched the Constellation, the most powerful production road-burner in Britain, capable of a genuine 115mph on the timing track. For a short while.

“Probably the fastest production roadster motorcycle being made today,” gushed the marketing blurb, “the Constellation is a real enthusiast’s machine.

The specially developed engine has special cams, high compression pistons, machined induction tracts, special valves, valve springs, etc.”

This all added up to over 50bhp, 10% more power than Triumph’s blistering new Bonneville could boast. Trouble was, this was also a monster 40% power increase over the Meteor’s original output – and ‘the engine cannae take the strain, captain’.

Things weren’t much better with the frame and running gear.

Enfield claimed that “magnificent steering and the well-known dual front brake and powerful seven-inch diameter rear brake make the Constellation a machine which can more than hold its own in any company”, but these sweeping statements didn’t hold true on a series of tight turns.

Any Norton featherbed could run rings around a Constellation, while Turner’s twins were quicker off the mark and easier to ride faster.

Then there were the reliability woes, which we chatted about back in the May issue of 2015.

If you buy an early (1958/59) Constellation today and it’s still in its original state of tune then you can successfully employ modern components and technology to cure the 700’s myriad issues – go talk to Allan at Hitchcocks Motorcycles.

Back in the day Enfield did it by gradually detuning the machine in 1960 and ’61, replacing it with the much-improved Interceptor for 1962. The Constellation enjoyed only a short spell as a super-sportster before it was humiliatingly demoted.

Once the Interceptor arrived, the Constellation was reincarnated as a sidecar tug; exactly the type of motorcycle it had been introduced to replace, you’ll recall.

The rev ceiling was dropped by 750rpm and the engine significantly detuned. The final Constellation was “produced specifically for the rider who requires a powerful machine.

The Constellation engine characteristics, with very high torque at relatively low engine speeds together with the standard fitment of sidecar gearing, steering damper, modified clutch and special suspension make the machine ideal for heavy duty sidecar work.”

This is why a Constellation today is generally worth no more than the Meteor or Super Meteor machines which preceded it, and you’ll need to return the 50bhp Connie back to 40bhp format to enjoy something like smooth-running reliability.

However, this doesn’t seem so awful for the classic rider of the 21st century. There are plenty of other options available if you want to roar around at 115mph, after all.

And in its later state of soft-tune, the big old Enfield turns out to be strangely suitable as an all-weather, long-distance classic tourer.

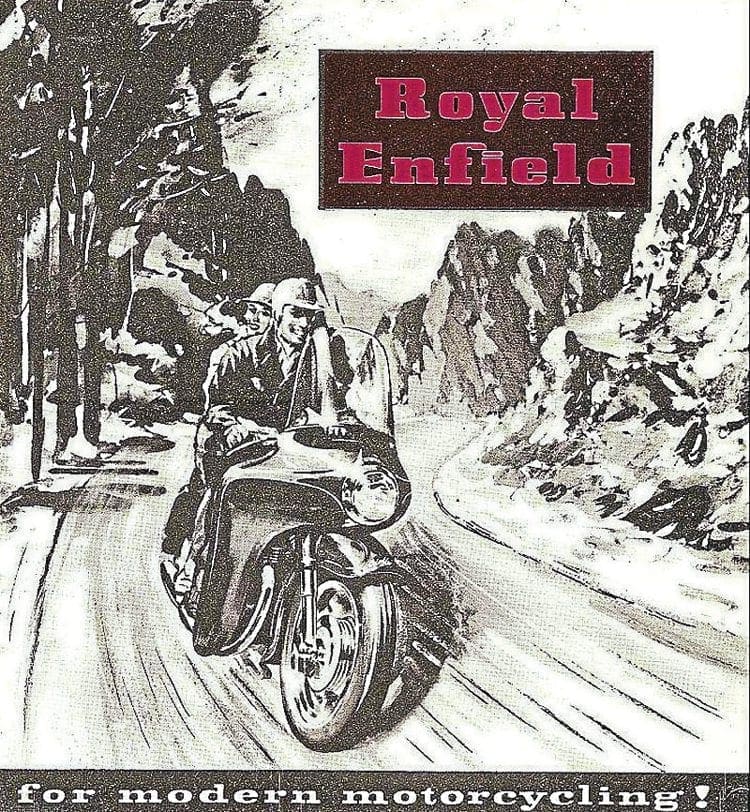

Enfield had much the same idea back in the 1950s, when it introduced its Airflow fairings to most of the firm’s models.

The performance of the 250 Clipper must’ve been somewhat blunted, but the full fairing makes an awful lot of sense on the 700.

From some angles, the design is 50 years ahead of its time. Check out the amalgamated side-panelling and tailpiece and extended front mudguard; the sweeping, sculpted lines of the fairing itself and the integrated instrument panel.

It’s all extremely practical, with smart gold coach-lining replacing the blizzard of chrome bling, and a fully enclosed drive chain.

Enfield also calculated that the Airflow aided top speed and fuel economy.

“This superbly styled fairing and front wheel guard, which are made from fibreglass reinforced polyester resin, give as near 100% weather protection as is possible on a two wheeled machine.

The ‘normally seated’ maximum speed of the machine is increased by 5-8% when Airflow is fitted, with an improvement of 20% in petrol consumption.

For the touring rider or the “road burner” the Airflow takes the sting out of bad weather riding and permits higher average speeds in perfect comfort and with complete weather protection.”

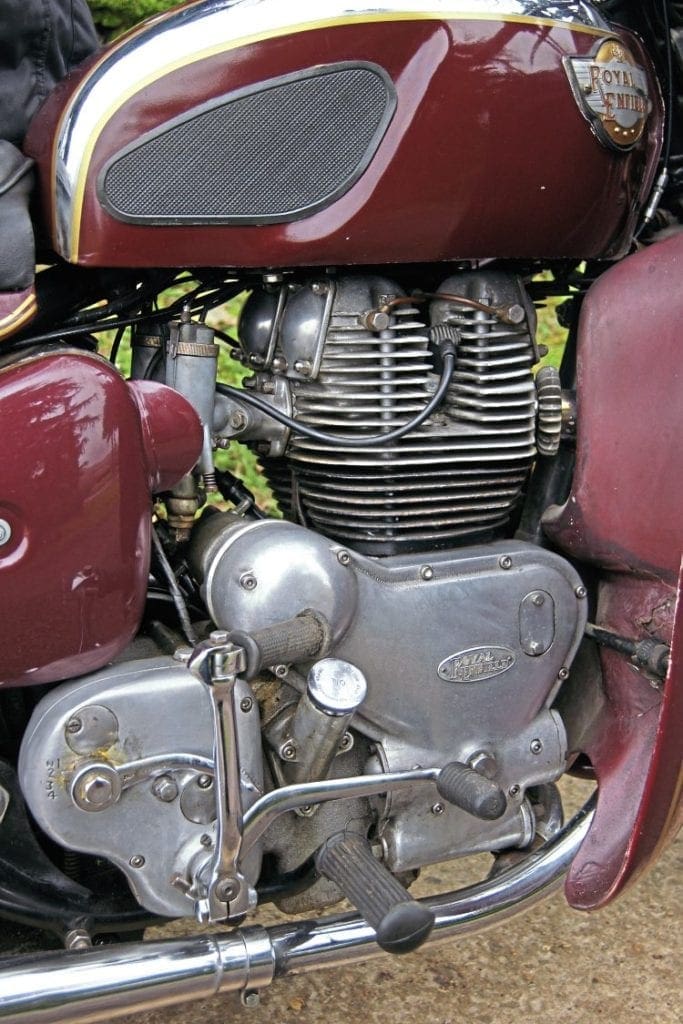

So if shopping for a Connie, what should you look for? Ideally you want an example which has already adopted the 1960-onwards mods. It should wear a pair of Monoblocs and not a TT9 carb.

You want the lighter, lower compression pistons and revised crankcases breathing arrangements.

Swap the scissor-action clutch for a conventional item, and go for silentbloc swinging arm bushes. Enthusiast owners might have added extra gussets to the swinging arm mountings, used the later cylinder head steady, and fitted sturdier engine plates. 12V electrics are ideal, and the front forks can be improved by borrowing bits from Honda’s 750-four.

You’d still be a brave man to set off in determined pursuit of 110-plus mph, but comfortable all-day cruising at 70mph and 50mpg should be pleasantly possible, with the torquey big twin turning over at a relaxed 3800rpm.

Enfield’s gearbox takes some getting used to: there is a definite technique which involves a distinct ‘pause’ while you let the revs fall and locating neutral is an acquired art.

The dual front brakes aren’t straightforward to set up so it’s worth paying a professional to do the job right.

Use oversize shoes and skim them back to increase the active surface area, and make sure they operate in tandem otherwise they’ll be less effective than a standard single stopper – not ideal with a full-faired motorcycle getting on for 450lb when fully fuelled.

Sort yourself out a soft-tune Constellation equipped with Royal Enfield’s Airflow fairing and… the sky’s the limit, surely?

PRICE GUIDE

£4500 to £6500

ALSO CONSIDER

Interceptor Mk2 (if you do want a bling bike which goes as good as it looks). Norton Commando Interstate (another long-legged classic tourer; even comes with a fairing in Interpol form). BMW R80RT (half the price, twice as practical; possibly half as interesting)

SPECIALIST

hitchcocksmotorcycles.com

OWNERS’ CLUB

REOC: royalenfield.org.uk

BUILT: 1958 to 1963 ENGINE: Air-cooled ohv parallel twin BORE / STROKE: 70mm x 90mm CAPACITY: 692cc COMPRESSION: 8.5:1 POWER: 51bhp @ 6250rpm CARBURETTOR: Amal TT9 IGNITION: Lucas K2F magneto CLUTCH: Dry multiplate GEARBOX: Four-speed Albion foot-change PRIMARY DRIVE: Duplex chain FRAME: Tubular steel cradle FRONT SUSPENSION: Hydraulic damped tele forks REAR SUSPENSION: Swinging arm, hydraulic damped twin shocks FRONT BRAKE: 2x 6 inch sls drums REAR BRAKE: 7 inch sls drum FRONT TYRE: 3.25 x 19 REAR TYRE: 3.50 x 19 SEAT HEIGHT: 31 inches WHEELBASE: 54 inches GROUND CLEARANCE: 5.5 inches WEIGHT: 425lb (part-fuelled, no fairing) FUEL CONSUMPTION: 50mpg average TOP SPEED: 115mph

Read more News and Features in the November 2019 issue of CBG –on sale now!