Ariel’s top of the range tourer is still more than capable of going the distance. If you look after its engine, that is

PHOTOS BY Rowena Hoseason

WHEN BUYING A typical Brit bike – a big single or one of the many variations on the parallel twin theme – a canny consumer can normally get away with taking a small risk on a non-runner.

You know the type: a bike which has been stored in a shed since its restoration a couple of decades ago; the kind of classic which initially clocked up minimal mileage for its MoT and Sunday runs, and hasn’t turned a wheel in five years.

Those motorcycles can often be bought for affordable sums and, if the gods of fortune smile upon you, can be recommissioned with fresh fluids, a magneto rebuild or new electronic ignition kit and new boots.

If your luck runs out and mechanical mayhem ensues, then an extensive selection of spare parts and expertise is widely available to get you back on the road reasonably easily.

Ariel’s Square Four, in any of its incarnations, is not a typical Brit.

When buying, your best bet is to find a machine which has been used regularly until recently by an enthusiast owner, so you can convince yourself that the four-cylinder engine – the thing which makes the Square so special – has been reconditioned to a suitable standard.

Alternatively, you should include the cost of a full engine overhaul into your own budget.

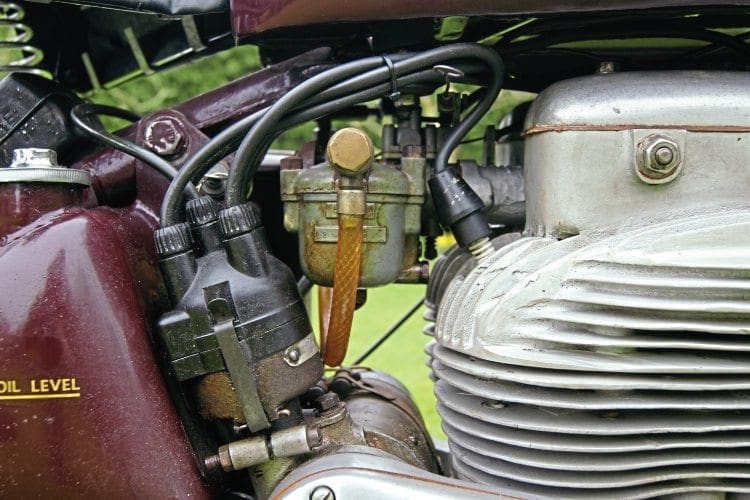

The worst may not happen (think ‘possible’ if not inevitable), but even the final models suffered from poor oiling, usually compromised by a blocked sludge trap, and overheating rear cylinders which can subsequently have a tendency to tighten up.

Damage to cranks, cases, conrods and even cylinders can ensue, necessitating extensive emergency surgery…

Assuming that everything goes swimmingly, what might you expect from your litre-class supersports machine? Well, you can stop that line of thinking straight away.

The Square was good for 92mph, flat out. The post-war 997cc tourers were no more rapid than many 650 twins of their time.

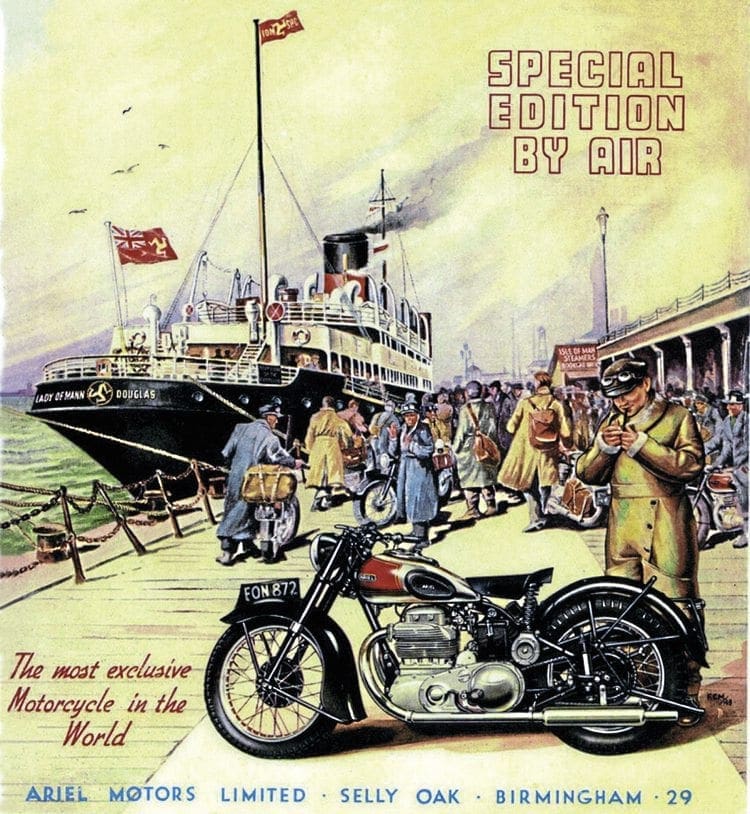

As befits a refined gentleman’s conveyance, a Square is all about effortless mid-range torque for relaxed long- distance riding. It’ll pull smoothly in top from as low as 12mph, so there’s no need to practise your rapid cog-swapping through the four-speed Burman box.

Nor is the chassis suitable for close-combat cornering. It’s comfortable and softly sprung, not especially well damped nor set up to hold a tight line.

Back in the early 1950s, test riders found the Square’s ‘combination of zestful performance and roly-poly handling diverting and, on the whole, congenial.’ MotorCycling reported ‘acceleration which gives 0 to 92mph in under half a minute’!

Yes, those were the days when speeds were measured in half-minutes. More importantly for the refined traveller, the ‘Squariel combines the docility of a sidevalve with the out-and-out performance that can be equalled by very few vehicles.’

The Square Four started as a twinkle in Edward Turner’s eye back in the 1920s when he worked at BSA.

After moving to Ariel, and enlisting the aid of engineer Bert Hopwood, Turner’s idea was made into metal in 1931 in the shape of the first 4F 500cc Square Four.

This remarkably compact powerplant was slotted into a twin downtube chassis similar to that used by Ariel’s 500 singles, using girder forks and a rigid back end.

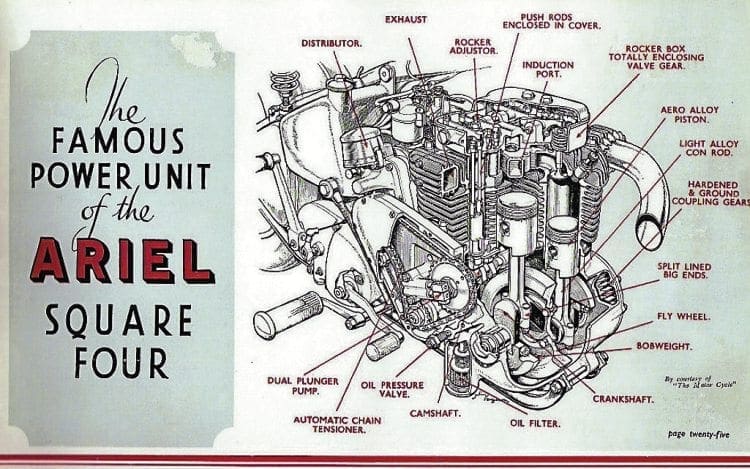

The original OHC engine is a bit like two parallel twins which shared a common crankcase with the two crankshafts geared together at the middle by mighty pinions, and a common cylinder block and head.

The overhead camgear was chain driven up the right-hand side of the engine. Early bikes used a hand-change, four-speed Burman gearbox.

Turner hoped to ‘provide a four-cylinder engine small enough for use in a solo motorcycle, yet producing ample power for really high performance without undue compression, racing cams or a big-choke carburettor.

I was aiming at the ultimate reliability with the minimum of attention’. However, ‘really high performance’ wasn’t quite on the cards. Instead the Square became a heavy tourer, famed for its long legs and relaxed ride.

When Turner moved on from Ariel, Val Page continued the Square’s developments and it grew to 600cc with a little more power, intended for use as a sidecar tug.

It was very smooth but somewhat sedate, and the engine was not easy to tune for ‘peppier’ performance. By the late 1930s the 997cc Square was introduced with an OHV pushrod, all-iron engine, alongside a similarly-engineered 600cc version.

The front end still used girder forks but the rear utilised Frank Anstey’s sprung rear suspension system as an optional extra.

The 997cc Square reappeared immediately after the war with oil-damped telescopic front forks instead of girders, but keeping that all-iron engine which had already demonstrated its tendency to overheat.

The Square was a massive machine for the time, weighing in at around 215kg, although the low saddle height of just 28 inches and good weight distribution made all that mass manageable.

A major redesign was needed for the Square to be suitable for the next decade, so for 1949 the new model 4G Mk1 was launched with an all-alloy engine running a 6:1 compression.

Although the bottom end was much the same as before, the cylinder head, valvegear, crankcases, rockerboxes, exhaust manifold and such were all overhauled.

These modifications helped the Square’s cooling and reduced its weight to under 200kg, as well as giving acceleration something of a boost.

Braking was provided by single leading shoe, seven-inch drum brakes at each end, and an eight-inch brake arrived in 1951. Fuel consumption wasn’t spectacular for the time, at between 40 and 50mpg.

The twin-pipe 4G Mk1 Square could exceed 90mph, and its gentle power delivery provided ideal propulsion for the fully-laden outfit, giving smooth, seamless acceleration from low revs – 35bhp went an awful long way in those days!

It helped that the 4G produced its peak power at just 5500rpm with that broad spread of tractable torque.

Another update in 1953 created the Mk2 4G, which featured the model’s fabulous four-pipe exhaust system.

Although Ariel built prototypes of a Mk3 with Earles forks in 1954, and experimented with swinging arm suspension, these weren’t put into production so the Mk2 ended the line when it was discontinued in 1959.

Riding a Square remains a singular experience. The power characteristics of the four-cylinder engine are nothing like those of Japanese fours and – to unfamiliar ears – its normal clatter sounds terminal even when the motor’s in perfect health.

Nor does a Square handle like a British twin. If the rear suspension has been well maintained then the steering is steady and predictable and more than capable of sustaining high speeds around fast sweepers.

But soggy forks, worn Anstey links and marginal brakes are an unforgettable (not in a good way) combination.

The final Mk2 is the most favoured incarnation for its increased oil capacity, full-width (but still not brilliant) brake, and splendid styling.

Whichever version you choose, and unless you never intend to turn a wheel, you’ll soon be totting up loyalty points with Ariel spares specialist Draganfly.

Happily, the excellent owners’ club has invested in manufacturing some essential spares, like high-quality conrods made to modern tolerances.

The AOMCC obviously feel much the same as historian Jeff Clew, who once commented that ‘it is very pleasing to know that Britain had a very practical four-cylinder model on the road so long ago, with its cylinders arranged in a form that is still quite unique today.’

PRICE GUIDE

£8000 to £25,000

(post-war models)

FAULTS & FOIBLES

Regular oil changes and sludge-trap cleaning essential. Top end oil leaks and blowing gaskets may indicate distorted heads. Original tinware very hard to replace. New conrods must be replaced in sets of four; must not be mixed with original items

ALSO CONSIDER

Hesketh V1000 (similar ethos and prices, also require dedicated enthusiast owners). Norton Classic (likewise smoothly unusual; budget for an engine rebuild)

SPECIALIST INFO

Draganfly Motorcycles

draganfly.co.uk

OWNERS’ CLUB

Ariel Owners’ MCC

arielownersmcc.co.uk

BUILT: 1936 to 1959 ENGINE: Air-cooled ohv four BORE / STROKE: 65mm x 75mm CAPACITY: 997cc COMPRESSION: 6:1 POWER: 34bhp @ 5400rpm TRANSMISSION: 4-speed Burman, positive stop CARBURETTOR: Solex FRAME: Tubular brazed FRONT SUSPENSION: Hydraulically damped tele forks REAR SUSPENSION: Anstey link plunger ELECTRICS: Lucas magdyno, 70W BRAKES: 7-inch drums FRONT TYRE: 3.25 x 19 REAR TYRE: 4.00 x 18 WHEELBASE: 56 inches GROUND CLEARANCE: 5 inches SADDLE HEIGHT: 28 inches WEIGHT: 475lb fuelled PRICE NEW: £195 in 1949 BRAKING: 32ft from 30mph ACCELERATION: 16s quarter mile TOP SPEED: 92mph All data for 4G two-pipe model