In this old motorcycle game of ours, fate can sometimes play a decent hand by laying in front of us a certain path, which eventually results in a machine that originally was not quite what we had planned. Take Dave Dawson’s Spitfire Scrambler, for example; it actually began life courtesy of a worn out alternator. Well, OK, not literally, but had it not been for a pal in need of a replacement alternator for his car, Dave would not have received the remains of a BSA engine in exchange for the required electrical component.

Born and bred in the villages on the east side of Lincoln city – which, if development continues, will soon become simply suburbs – he was fortunate to live on a farm and have a father with a keen interest in motorcycles. It was an idyllic situation for a young lad, plenty of old bikes and plenty of space to ride them without today’s curse of litigation, noise pollution, nimbys and over-zealous police out for the easy kill.

The farm, by its very nature, had a plentiful supply of old tractors, lorries and cars too, all of which formed a very thorough grounding in the workings of the internal combustion engine, transmission and the other mechanical systems connected to vehicular forward (and reverse of course) motion. At 15 years old, Dave rebuilt the engine of his sister’s boyfriend’s BSA A7 chopper. Dave says: “I think that’s why I prefer the older vehicles now, they’re mendable.”

A natural bent towards perfection also served him well in his career, as he is currently employed as shop foreman at Holland Brothers, top Jaguar specialists in Lincoln. Indeed, as well as another couple of tasty machines in his workshop which will perhaps grace these pages in future issues, there is a classic Mk 1 Escort Mexico, a superb but presently body-less Morris Eight and an immaculate, scarlet, convertible XJS Jaguar in his drive.

His first road machine was the now much sought after 50cc FS1-E Yamaha, followed by a 250cc Honda on which he passed his test. Several other everyday machines passed through his hands but were of little interest as he soon realised he preferred the older machines. His reward for rescuing his friend from the darkness was the remains of a B31 chopper frame and 500cc Shooting Star engine and gearbox. It had thrown a con-rod sometime in the past and though it had damaged the big-fin barrel, the cases were fortunately intact.

At this time, Dave had no plans to build a Spitfire Scrambler and merely set about rebuilding the engine. The crank was actually in good condition but Dave had it ground to first undersize (-10 thou) on the big ends and –20 thou on the mains, obtaining the required sized bearings from Kidderminster Motorcycles. He found a small fin barrel and set of plus 20 pistons at the Stafford Show jumble for just £10, but preferred the look of the original barrel so took another look at it.

‘The cylinder head was in good condition with nothing required other than a light grinding of the valves, but the rocker cover had a number of cracks where someone previously had obviously gone mad with the socket wrench, over-tightening a number of the bolts.’

It was damaged at the bottom of the skirt, but there was no more metal missing than on the standard 650cc barrel, which has cutaways to accommodate the rod’s movement on the bigger throw, so he simply machined away the metal as per the bigger barrel – problem solved. With new rings, the plus 40 set up works and looks a treat. The cylinder head was in good condition with nothing required other than a light grinding of the valves, but the rocker cover had a number of cracks where someone previously had obviously gone mad with the socket wrench, over-tightening a number of the bolts. A pal had little trouble welding these and the repairs are invisible.

The cam was completely worn out so a re-profiled replacement was picked up locally, but Dave feels that something is not quite right with it. “The marks didn’t line up to start with and though it works well enough, I reckon it should go a bit better at the top end. I shall replace it with a proper Spitfire cam in due course, but I don’t really want to pull it down again at the moment.”

Carburation-wise, it arrived fitted with a Mk 1 Concentric but Dave has replaced that with the correct Monobloc. The magneto was weary but he spotted a new old stock armature on an internet auction site and quickly snapped it up. The dynamo was old, naturally, and he decided to discard the segments from its commutator, but canny Dave got round the problem by buying a brand new armature from Abbey Spares, which had the threaded end section broken off. He machined the end flat, bored and threaded the shaft and the dynamo pinion is now held in place by a through bolt. It works like a brand new one should and the voltage is taken care of by a Podtronic electronic regulator tucked up nicely beneath the seat – six volt lights have never been so good!

The transmission system was again in good order, the clutch and primary arrangement needing no attention beyond a clean. The gearbox, however, had a bush missing. “I could kick myself really,” says Dave. “I took the end cover off to replace a spring but seeing as all the gears selected easily and the shafts spun freely, I didn’t investigate any further. Of course, it was only when I rode it that I realised something was wrong. Fortunately, there was no damage done and with a new bush fitted, all was well again.” The bush, sundry fasteners and odd electrical parts were all sourced from Draganfly Motorcycles.

While all this was going on, Dave was also checking out the various styles of the BSA twin, initially heading toward the stock Shooting Star two tone green job. He says: “I hadn’t given the American spec much thought to start with but the more I looked at the catalogue images, the more I liked them and seeing as I was having to source parts to build it up from scratch anyway, it was as easy to go that way as the other.”

‘Paying close attention to the catalogue diagrams, Dave cut off all the unnecessary brackets and the footrest lugs and in a chance telephone conversation with Cake Street Classics, he discovered that they had just had manufactured a batch of the correct clamp-on, fold-up footrests for the Spitfire Scrambler…’

First up was a frame, which he bought at Newark Autojumble. It came with no documents so Roy Bacon supplied him with a dating certificate which equated to a 1959 model and an age related plate was eventually secured. Paying close attention to the catalogue diagrams, Dave cut off all the unnecessary brackets and the footrest lugs and in a chance telephone conversation with Cake Street Classics, he discovered that they had just had manufactured a batch of the correct clamp-on, fold-up footrests for the Spitfire Scrambler and, to add icing to the cake, they also had an original fuel tank, repaired and replated and simply in need of the required paint job!

The forks were built from parts sourced at various autojumbles and Abbey Spares. As standard, the Spitfire Scrambler was not supplied with lights but as Dave wanted to use his bike without restriction, he fitted a pair of upper fork shrouds with headlamp securing ears and went with a period style lighting kit from Kidderminster Motorcycles. On the subject of electrical components, Dave dismantled the burned out Altette hooter and rewound it himself, Lyn Issaacs – aka Taff the Horn – supplying a new chrome rim and domed nuts.

The standard specification 1959 full width steel drums were used, the front sourced again from Newark Autojumble, the rear already ‘in stock’ as part of a 5.00 x 16in wheel from the B31 chopper set up. “I cut it out of the wheel and reused it. It was a shame there was nothing else salvageable from it,” he says. Dave buffed the brake plates, painted the hubs, and the new CWC chrome rims supplied by Abbey Spares were built up using stock galvanised wire spokes. “It wasn’t too difficult because they’re all straight spokes,” says Dave. A pal checked the drums for ovality and Dave fitted new linings to the shoes made from that material of which the very mention has many people falling into fits of apoplexy, but which has sensible people lamenting its demise, in the retardation stakes.

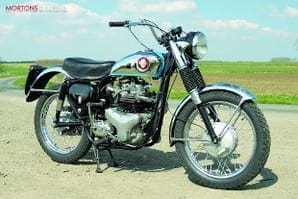

The Scrambler has no toolbox and the required oil tank was another Newark Autojumble find. Dave undertook all the general paintwork, using black cellulose for the frame, oil tank, fork sliders etc. A professional body shop friend was entrusted to paint the fuel tank, Dave choosing a blue he liked rather than aiming for true catalogue perfection – probably red – and a smart job he made too, being set off by the fabulous Spitfire Scrambler decal amidships.

The pattern mudguards and the sweeping, straight through exhausts were courtesy of Burton Bike Bits. Dave made up the stainless steel mudguard stays but was less than happy with the line of the exhausts. He says: “They fitted perfectly and were just as they should have been, no problem there, but as they curved up toward the back together, the lower pipe curved ‘later’ than the top and there was a gap between them. It was purely aesthetics but I didn’t like it, so I shortened the lower pipe at the head stub and now they run perfectly together.” I have to admit I agree with him, they look terrific.

Likewise the saddle, made up by Dave and covered by RK Leighton, is just so right. Dave says: “I found an old seat base at Newark again, which had been damaged and cut at the back end. It was no good really for anything except for what I needed. I got it for next to nothing, bought a Leighton cover, cut the base to size, made up my own foam and that was it, sorted.”

With any classic machine that has an off road appearance, the tyre choice is important and the 19in Dunlop K70 Gold Seals are just chunky enough to give the macho look while maintaining common-sense for everyday road use.

Dave runs his mini Spitfire on Millers excellent Millerol Classic 50 and changes it fairly regularly. One of his own modifications lurks out of sight beneath the engine – he has made up his own sump plug with an integral magnet to catch any potential nasties which may avoid the BSA’s basic filtration system. He also adds octane booster to the basic unleaded on which it runs. “I’m using Wurth at the moment, because a mate’s got a barrow load of the stuff,” says Dave.

So, under the beautiful sunshine of a perfect Easter weekend, it was time to sample his handiwork. Dave has the carburation set slightly rich, so on such a hot day the air lever can be wound fully open from cold and with the manual advance and retard lever set almost half way and the fuel tap open, I gently pressed the kick start lever to get an initial feel for what I was up against – and to my utter surprise, the engine burbled into life. To say I was flabbergasted is an understatement, it was honestly a press, not a kick. I looked up to see Dave grinning and could immediately see the importance of that magneto armature puchase, these sparks are good!

Now, those exhausts, just fantastic! There is a kind of baffle in the end of each pipe to satisfy the MoT man, but I don’t think the neighbours would rate it too highly if you were on the early morning shift. However, we weren’t, and with a blip of the throttle it was a toe up into bottom gear and a steady, considerate tootle through the village and out into flat open B roads of Bomber County.

Dave’s about the same size as yours truly so the BSA felt ergonomically perfect, footrests and bars working for a comfortable riding position, though one or two potholes emphasised that Dave’s choice of seat foam could perhaps have been a little more dense.

“Watch the front brake, it’s crap,” were Dave’s last words as I set off, but to be honest I don’t know against what he was comparing it, because I thought it was fine and had the forks dipping to the point of almost locking the wheel. Perhaps the constant stop-starts for snapper Langton had warmed it up more than usual, in which case perhaps we did it some good.

The BSA swinging arm frame set up, in my humble opinion, is to perhaps all but the hardest racer types, as good a frame as anything of the period, including the Featherbed, and Dave’s set up is as good as it gets with no wallowing and sticking to a line despite the best efforts of Lincolnshire’s back roads to unsettle it.

With plenty of clutch work on a hot day, I was waiting to see how long it would be before it complained but to its credit, there was never an inkling of slip, which naturally made life much easier when accelerating back and forth for the camera.

It is said that in general the 500cc twins, from whichever factory, are the ‘sweetest’, and as the Americans allegedly forced us to increase capacity more and more, this sweetness was lost. Well, as a former Shooting Star owner, I heartily back up this statement, and Dave’s little Spitfire brought back many memories, though I seem to think that when opened up mine went a little better at the top – perhaps he’s right about that cam, a 357 Spitfire profile I’m sure would let it breath deeper – it never sounded half as good as this one though. At a steady 60 or so mph, there was no buzzing or vibration, and I could have quite happily ridden straight past Dave’s home and off into the sunset.

He’s considering seeking out a 650cc engine to make it right but I don’t know whether that would improve anything other than maybe top speed. You could always build another Dave, I’d leave this Little Spitfire just as it is.