Not all American twin-cylinder bikes are Harleys made for cruising. This little-known marque was a collaboration with Laverda to bring the US a sporty edge.

Words by Oli Hulme Photos by James Archibald

For reasons that are hard to fathom, American motorcycle manufacturers seem to struggle making motorcycles that are not big V-twins, with established companies resorting to foreign firms to provide small and medium-capacity bikes. Most famously, Harley-Davidson bought Aermacchi, while Indians had a small sidevalve single made by Blackpool’s Brockhouse to sell as an Indian, tried a Vincent engine, and imported rebadged Royal Enfields. In the Clymer years, Indians came with engines from Velocette and Royal Enfield and Italjet frames, and there were Taiwanese-made two-stroke Indian tiddlers.

One of the more unusual efforts to slap on the Stars and Stripes was American Eagle Motorcycles – a great name for a motorcycle company, even if it didn’t actually make any motorcycles. It was established in 1967 by former Honda and Suzuki concessionaire Jack McCormack, the man who came up with the slogan “you meet the nicest people on a Honda”. McCormack started American Eagle when Suzuki took its importation operation off him and moved it in-house in the USA. He sued them, won, and used the substantial pay-out to set up the new company.

There was never any American Eagle motorcycle factory. He started out with a big ad budget and small racing team while selling off-road bikes in a classic example of ‘Badge Engineering’. These were made in the UK, by Sprite Engineering in Oldbury, in the West Midlands, which did similar deals with Belgian and Australian companies. Sprite machines originally used engines developed from Villiers designs, but the American Eagle-badged bikes used Sachs and Husqvarna-based engines. McCormack also brought in bikes built by Italjet, and badged up Kawasaki off-roaders and road bikes, including a version of the Kawasaki A7 twin. Many of these bikes had American Eagle badges cast into the engine casings.

Then he decided he needed a big road bike to grab the buyer’s attention and chose as his flagship a rebadged Laverda twin. McCormack said it was he who persuaded Laverda to take it out to 750cc and the bike was being produced exclusively for American Eagle, a claim parroted in the US motorcycle press. American Eagle also sold a 150 version of a Laverda off-roader.

McCormack enlisted the help of Evel Knievel to promote American Eagle, and the daredevil stunt rider used a 750cc-engined Super Sport-derived model in late 1969 and early 1970 instead of his previous Triumphs. The Knievel American Eagles were the first to use the stunt rider’s ‘Stars and bars’ Confederate battle flag-style colour scheme that became his signature look.

While using the heavyweight Laverda to perform jumps, he crashed several times. Two Knievel American Eagles now sit in a museum in Topeka, Kansas.

When the Honda 750 and BSA-Triumph Triples arrived in US showrooms, American Eagle’s 750 sports bike exclusivity evaporated and the Honda, in particular, was $200 cheaper. American Eagle went bust in 1970. Italjet, Kawasaki and Laverda were able to survive the unpaid bills. Sprite took a much bigger hit and very nearly went out of busines, but it survived, making bikes and components into the late 1970s. These days, Sprite makes motorhomes and caravans.

An all-new Italian twin for the US

The Laverda motorcycle company was set up in 1947 by Francesco Laverda, who worked with engineer Luciano Zen to create a range of high-quality lightweights to fill the need in postwar Italy for personal transport. The resulting machines successfully took part in many endurance events. Although the early focus was on small bikes, in the early 1960s Francesco’s son, Massimo, wanted to launch a new large-capacity machine. After some heated discussion, in 1965 Francesco allowed his son, then still aged in his early 20s, to go ahead with the concept, with the help of Luciano Zen, to create a 650cc twin.

While 650cc doesn’t sound big by today’s standards, in 1966 it was a superbike. The 650 appeared at the Earls Court Show in 1966. It isn’t clear whether, when Jack McCormack asked for a 750, Laverda had already decided to make the engine bigger, but whatever the truth, Zen quickly made the changes needed. The new American Eagle Super Sports and GT had a 750 engine, which hit the US market first. Many pundits felt the engine was, on the face of it, a beefed-up version of the ohc Honda twin fitted to the C77 and CB77 twins. What it wasn’t, though, was a copy. Not entirely accurate legend has it that Zen simply increased the dimensions of everything on the Honda’s engines and precision-engineered the resulting design, yet Zen’s design was far more sophisticated than the Honda. Honda had used a 180-degree crank on the CB77 and a 360-degree crank on the earlier C77. Zen plumped for the 360 design, like the British parallel twins, so the pistons moved up and down together. There were roller bearings on the crankshaft, double-caged roller bearings on the big ends, and ball and roller bearings all over the gearbox and a triplex primary drive chain. There were lots of supporting webs in the crankcase, which was horizontally split, Japanese style, and the pistons were made for Laverda by Mondial. In the one-piece cylinder head were four roller bearings holding the camshafts and a duplex cam chain. The oil pump could handle three litres of lubricant a minute. The engine was hung off a tubular spine frame that used the engine as a stressed member. Two robust tubes ran from the top of steering head to the rear of the seat, two more tubes ran up from the swingarm pivot, looped up alongside the two upper tubes and then curved down to the bottom of the steering head.

Laverda staked a claim to the reliability of its equipment by not fitting a kick-start.

American Eagle offerings

American Eagle badged up two versions as the Super Sport and the GT. Once it went on sale in Europe, Laverda dubbed the bike the 750S. The GT used the Laverda tank, while the Super Sport had a slimmer fibreglass offering that followed the lines of smaller American Eagle machines.

Unlike other American Eagle models, there were no branded casings, with Laverda’s name proudly cut into the alloy. During the early production run, equipment came from German, Italian and British manufacturers. The American Eagle models had a 230mm Grimeca drum brake at the front, a 200mm one at the back, CEV lights and Smiths instruments, which used a curious and effective rubber band mounting arrangement. Ceriani provided the forks and shocks. There was a belt-driven Bosch generator, a chain-driven Bosch electric start, and a Bosch 24ah battery, bringing German quality to Italian flair. The headlamp was of Laverda’s own design. There were levers from Smiths and the carbs were 30mm pumpers from Dell’Orto.

The American Eagle Super Sport claimed to have about 8bhp more than the GT or Laverda version. How this was achieved is unclear, so perhaps it was just publicist hype.

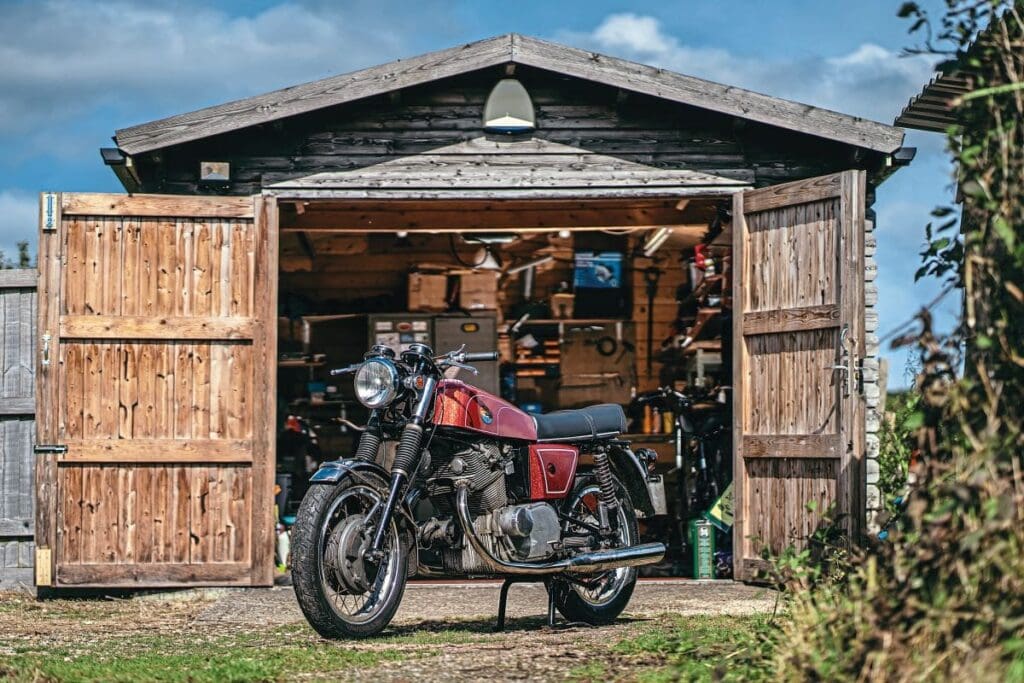

It was the look of the Super Sport that marked it out as an American Eagle. There was a skinny glass fibre petrol tank in red metalflake and American Eagle side panels with white pinstripes. There were high, braced bars and a prominent starter button.

Laverda’s link with American Eagle did not last long, and when McCormack’s company went bust in 1970, Laverdas were reintroduced to the US market with their own name on the tank. The 750SF with Laverda’s own brakes arrived in 1970, becoming the backbone of Laverda’s range and establishing the company as one of the great manufacturers of motorcycles of quality. American Eagle foundered in 1970, and Laverdas became Laverda all over the world.

Riding an Eagle

If you use a single word to describe the American Eagle Super Sport, ‘beefy’ would be good. Heavy as a four, yet almost as slender as a British twin, it has serious presence. The thundering Laverda engine and shiny metalflake fibreglass bodywork are an impressive combination. Max, the owner, sold his BSA M20 and used the money to buy it from a Laverda collector who hadn’t had it running, and they had got it from another Laverda collector who hadn’t had it running, so it has all the quirks of a motorcycle that hasn’t been out, much, for quite a few decades. For reasons best known to a previous owner, the wide, braced bars have been replaced with a narrow and low set from a much smaller machine, and the enormous starter button has been relocated from the right-hand handlebar to the middle of the yoke, meaning you can’t operate the steering damper. It’s not immediately apparent why this was done, but it means the bike can be started by pressing the button with the left hand while keeping a hand on the throttle with the right. As mentioned, Laverda’s confidence in its Bosch starter was such that it didn’t fit a kick-start. The low and narrow bars over the weighty front end make steering quite heavy at low speeds, too. I gave it half choke on the bar-mounted, British-style lever and the engine was off and running. It seemed only kind to let the oil circulate a little, so I let the choke off, looked at the currently flickering generator light, and revved it to about 1000rpm to get it to go out. I pulled in the clutch and it slipped into gear.

According to the original publicity, Laverda did something clever with the gearshift mechanism, involving a steel sheath over an aluminium selector drum, which helped reduce the clunkiness common to big twins of the period – and it does seem to have worked. This bike is markedly easier on the right foot than most. The later SF750s had a reputation for a heavy clutch action, requiring extended clutch arms to make life easier. Either this isn’t the case with the American Eagle or I’m used to heavy clutches. From first into second, the Super Sport rapidly gathers momentum, the previously low-speed, heavy steering becoming nicely positive while the low-barred riding position gives the rider a head-first and aggressive stance. The touring height footrests mean the rider isn’t cramped as one might be with a more café racer-type stance. Handling and performance became better the harder it rode. The Ceriani forks and oil-damped shocks are firm but not uncomfortable. You steer it, rather than chuck it about. I clamped my knees into the tank old-style, as this is much more old-style sports bike, rather than letting-it-all-hang-out territory.

Knowing the fuel level was low, I was gentle with it for the first few miles. Then, after splashing some E5 into the tiny tank, being extra-careful not to spill any on the metalflake paint job for fear of watching it dissolve, I headed back at a more enervating pace. Without the fear that I was about to coast to a halt, I gave it few handfuls and found a sweet spot somewhere between 4000-5000rpm. Below that and the old Dell’Orto carbs seemed to labour a bit; above 6000 is an appreciable buzz that would have become wearing on a long run.

Brake operation is unusual, as it seems to be two-stage, with half-braking for progressive slowing, while a big handful stops it on a sixpence. The front brake on the American Eagle is not the legendary item of the later Laverda SF and SFC, but a Grimeca offering like that fitted to many other period Italian bikes.

It handles sweetly, growls along nicely, and gives you a sense of aggressive well-being. All you could want from a motorcycle, really.

No matter what badge there is on the tank, the 750 is a robust machine and can be very reliable. Keeping the battery charged and up to snuff on a bike with no kick-start is a must; if it has been standing for a while, you will need to clean the carbs, but the square slide Dell’Ortos are well catered for by Eurocarbs in the UK, and updated round slide Dell’Ortos are available too – at a price. Unlike a lot of early 1970s Italian bikes, the Laverda can survive inclement conditions reasonably well, as long as it gets regular post-ride wipe downs, though some ancillary parts might be hard to find.

Max found the rear brake shoes had fallen apart and had some made.

The major issue on a Super Sport is the bodywork. On the GT, the petrol tank is the steel Laverda original, but on the Super Sport, the glass fibre tank, along with the side panels, are some of the few actual American parts. This will not like even low ethanol petrol, and E10 is likely to eat through it in short order, so it will need lining with a good ethanol-proof liner. Finding replacements is likely impossible. The seat foam on Max’s bike had crumbled, so Max had new foam cut, and the battered original cover had the rear badge panel cut out and expertly stitched into a new cover.

Buying an Eagle

In the 1970s, American Eagle Laverda machines often met the fate of many a failed attempt to encourage US motorcyclists to part with their money – relegated to the backs of garages and sheds, languishing for many years, a few packed into containers by British importers in the 1980s and 1990s, when they were snapped up by UK racers looking for a big twin to campaign. It is estimated that just 150 were made of both types. Their rarity and the recently-recalled Knievel connection has seen the Super Sport significantly rise in value, particularly in the US. A concours condition Super Sport now stands at upwards of $14,000, and even a poor example will set an American buyer back $6000.

Specification

1969 American Eagle 750 Super Sport

ENGINE: SOHC parallel twin BORE AND STROKE: 80 x 74mm POWER: 68bhp CAPACITY: 744cc COMPRESSION RATIO: 9.6:1 CArburettors: 2x Dell Orto VHB 30mm ELECTRICS: 12v Bosch belt-driven generator SUSPENSION: 35mm Ceriani telescopic forks, twin Ceriani oil-damped shocks BRAKES: 9in (230mm) TLS drum front; 8in (200mm) TLS drum rear TYRES: 3.50 x 18in front; 4.00 x 18in rear WHEELBASE: 1500mm (59.2in) WEIGHT: 229kg (498lb) Top speed: 115mph

Owners’ Club

International Laverda Owners’ Club

www.iloc.co.uk