Easy to ride, simple to maintain, economical and reliable. AJS and Matchless singles offer a lot of variety and a little performance, too

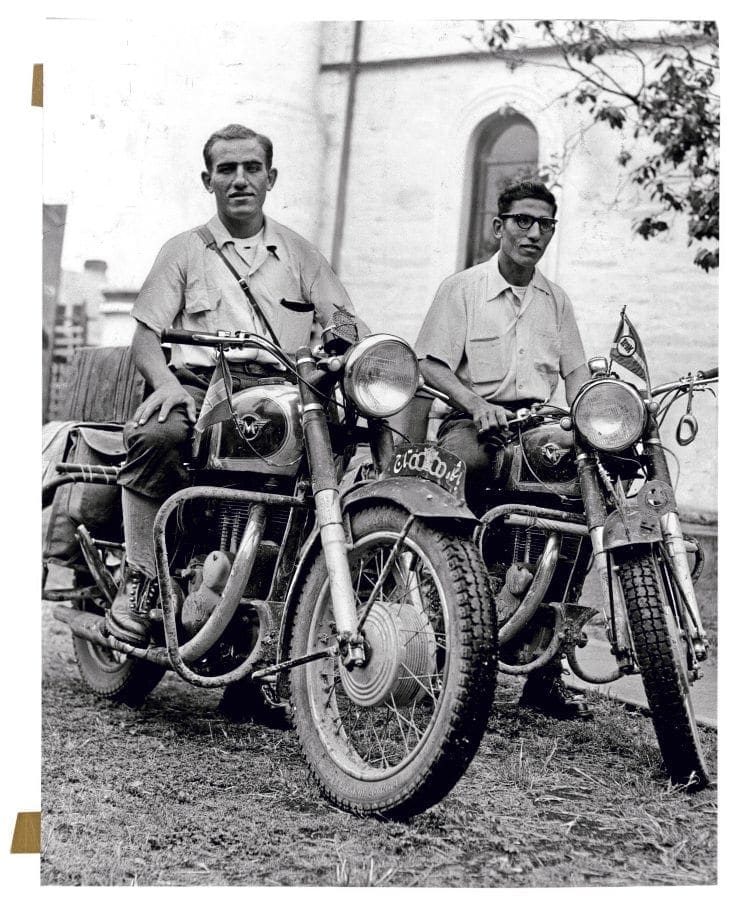

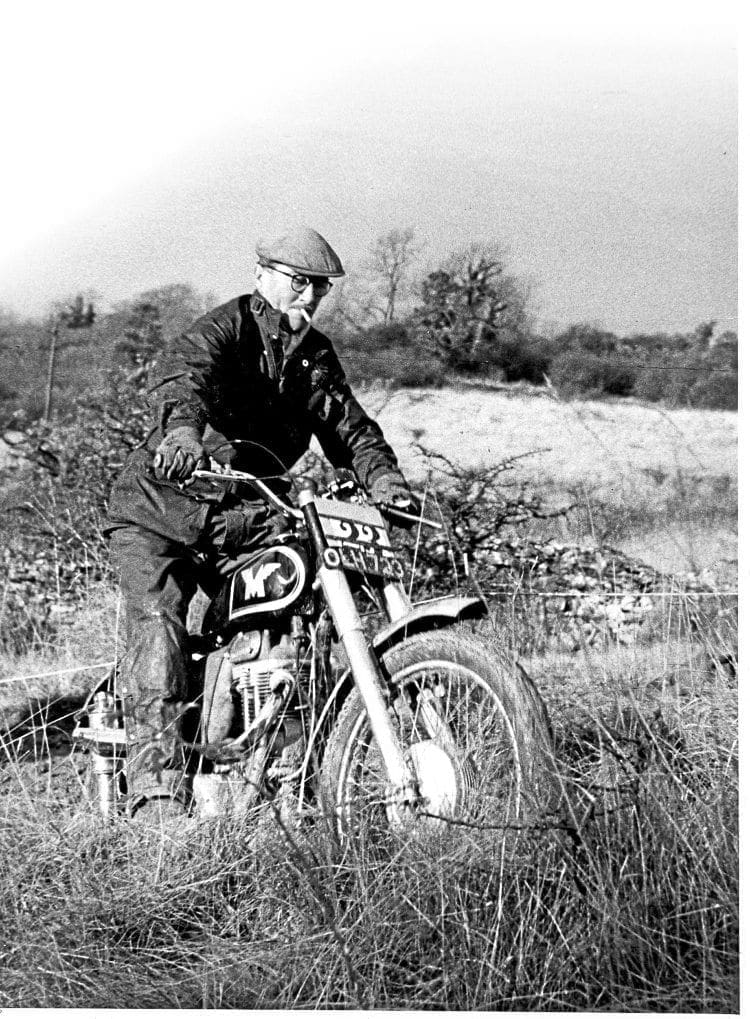

PHOTOS: JANE SKAYMAN/Mortons archive, Martin Peacock, Frank Westworth

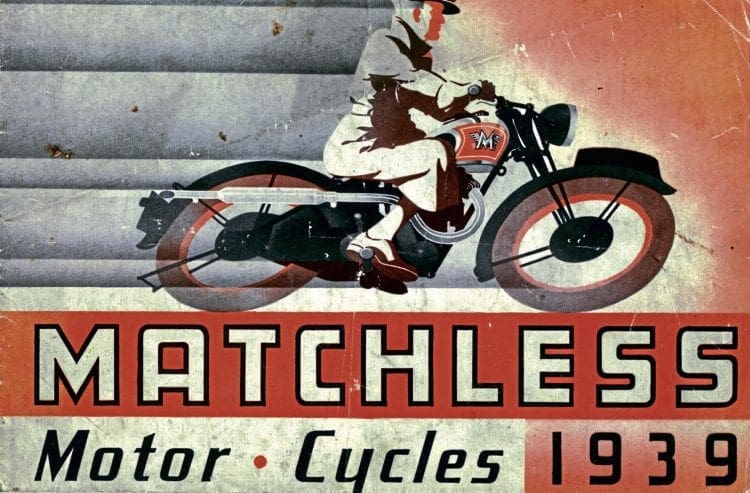

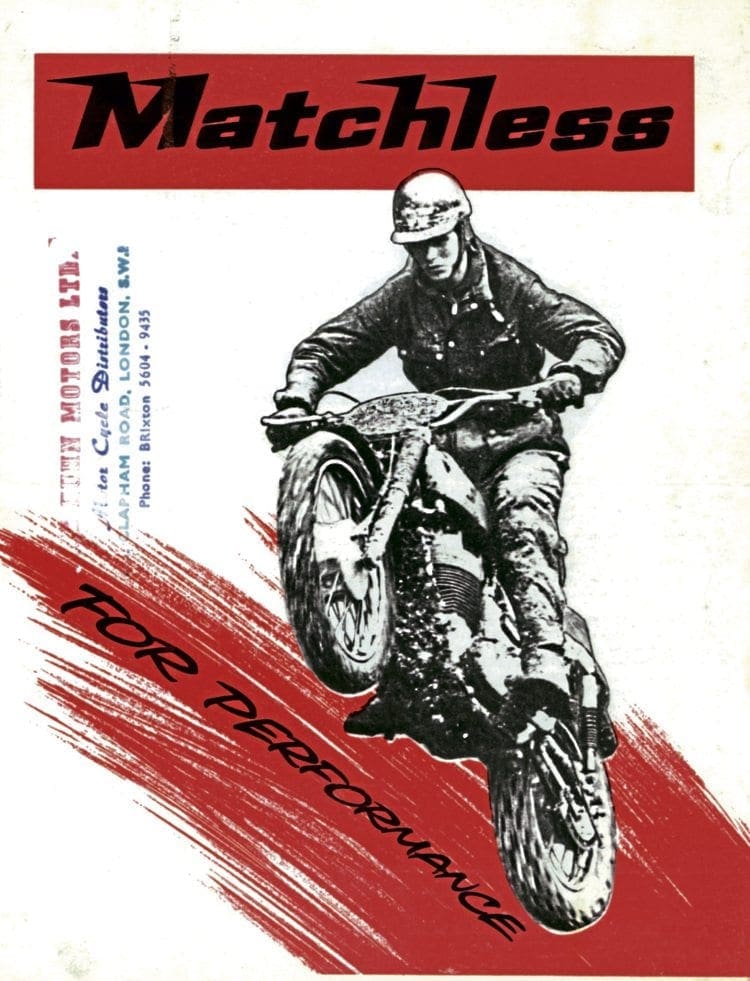

After the end of the Second World War, Matchless and AJS were in a pretty strong position.

Like BSA, and to a lesser extent Norton, their parent company AMC had been supplying bikes to the forces for most of the duration.

That bike, the Matchless G3L (L for ‘Light’) was regarded by many as the best of the despatch riders’ tools, and formed the basis for the first of the civilian models to bark their way from the London factory when hostilities ended.

The AMC single engine had been in production right through the traumas of the war, and almost all that was required for the transition to civilian life was a coat of lustrous black to replace the olive drab, and a lot of polishing for the power train’s covers.

The Engine

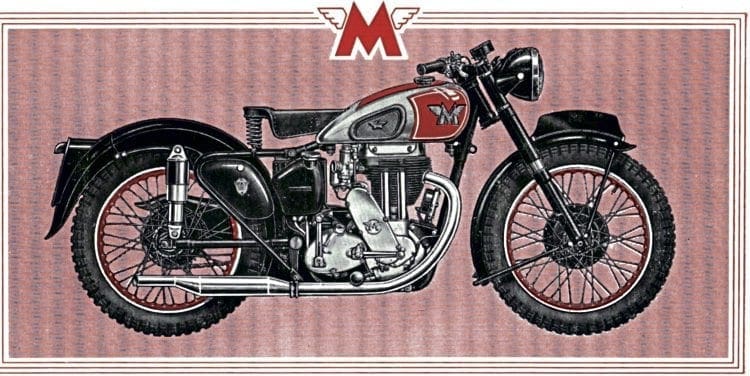

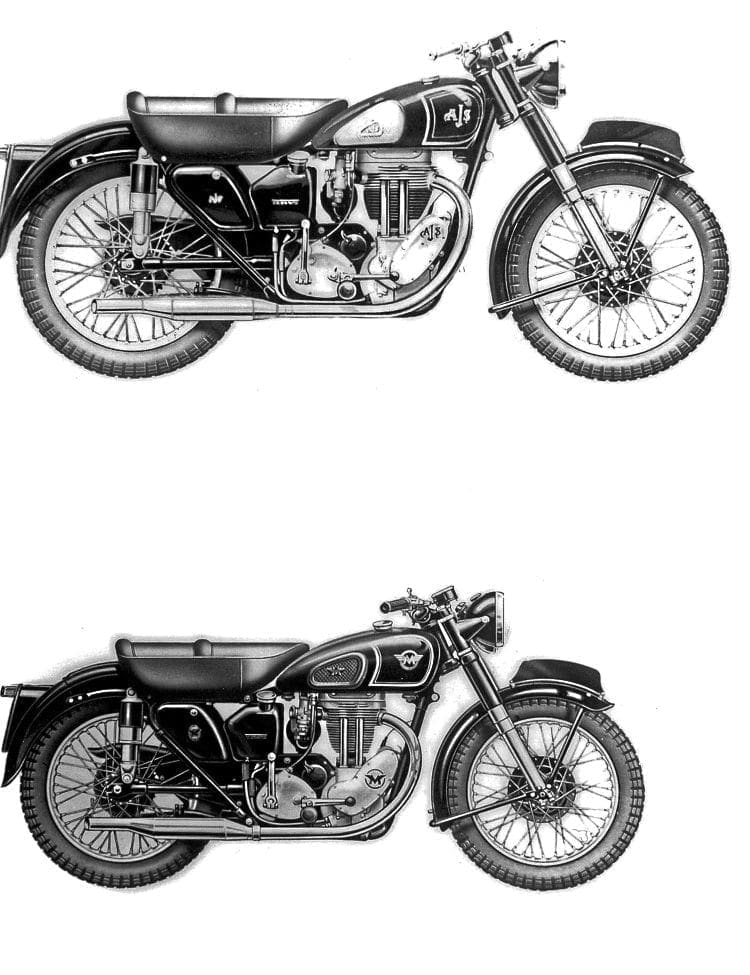

The Matchless and AJS single engine’s design was typical big Brit: long stroke, iron barrel, iron head, heavy flywheels and long pushrods.

This low-revving, mechanically quiet power plant, sweet in both 350 and 500cc formats, is one of the serious charmers from the period, and although it’s conventional in most ways, it does have its quirks.

These include an unusual oil pump plunger that both rotates (it’s driven at 90 degrees from the crankshaft) and reciprocates (the rotating plunger has an eccentric slot, which moves over a fixed pin, thus reciprocating lengthways), and a quaint drive to the dynamo.

Unlike many designs of the immediate postwar period, the AMC engine does not make use of the Lucas magdyno. Instead, drive to the magneto is by chain from either the exhaust (AJS) or inlet cam (Matchless).

You can work out where the mag is mounted on the two marques for yourself! The dynamo, which inhabits a space between engine and gearbox, is driven by a chain running inside the primary chain and sharing the (usually leaky) chaincase with it. This must have made sense to someone, we assume.

The single-strand primary chain, which was only occasionally wrecked by the breakage of a never-adjusted dynamo chain, transmitted power via an excellent Burman clutch to an equally excellent Burman four-speed gearbox, an arrangement that survived until both were replaced by AMC’s own – very similar – design in 1956.

Carburation was, inevitably, by Amal, usually unfiltered and rarely unduly sensitive to either adjustment or wear, although there are those who feel that the Amals can struggle with modern fuels.

Electrics are all familiar Lucas items, although as mentioned before AMC didn’t use the magdyno, preferring to install the SR1 magneto at the front of the cylinder on the AJS and at the rear on the Matchless, until Matchless swapped over to the AJS way in 1952.

The same year saw the change from Burman’s CP or BA gearbox to the B52. The dynamos were Lucas E3 items, and the voltage regulators were whichever version of the MCR2 Lucas were supplying in the build year.

The engine was developed with the urgency familiar to British bike fans, ie. remarkably slowly, and almost all the changes were retro-fittable.

Almost any part from almost any AMC single can be fitted to almost any other.

Hence you can occasionally come across very eccentric combinations of major components, a common one being the 500 single that started out as a 350.

A hint: AJS 500 singles are always engine-numbered with the prefix ‘18’ (350s are ‘16’); Matchless 500s ‘G80’ (350s ‘G3’). The problem with this simple conversion is that unless the fly-wheel assembly was changed at the same time, its balance will be wrong (the 500 has a heavier piston) and what should be a pleasantly smooth and woffly engine can instead vibrate like a late BSA twin.

Major changes over the years include the disappearance of the attractive but functionally flawed tin primary chaincase (actually pressed steel, but tradition refers to them as stannic rather than ferrous in nature) in 1957, and the handsome (but leak-prone) chrome pushrod tubes were cast into the barrel in 1962 (for the 350s) and 1963 (for the 500s).

The tin chaincase’s legendary ability to leak its lube can be viewed as a gentle eccentricity in these days of relatively low classic mileages, but beware – running dry will not only wreck the chains but can also wear the clutch rapidly and can almost destroy the big engine shock absorber which lives on the drive-side crank outboard of the sprocket.

This shock absorber is a pair of spring-loaded cams working against a spring which absorbs some of the shocks (really!) from the engine’s power pulses.

Dry operation can chew up the splines of the crankshaft’s drive-side axle really badly. Then the engine runs mysteriously roughly, and replacement requires a complete dismantling of the crank itself to replace the axle… and great expense.

Alternator electrics with coil ignition replaced the old magneto and dynamo for 1958, which spoiled (some say) the looks by eliminating the handsome magneto chaincase but improved the functionality of the machines.

Oddly, just before they went bump in 1966, and given that sales of heavy singles were hardly buoyant, AMC substantially redesigned their aged but charming banger engine for 1964.

Although visually the changes were less than obvious, in fact the engine’s vital dimensions had been changed, to shorten the stroke, and the quaint rotating plunger oil pump had been replaced by a Norton-type gear device.

Very few of the 1964-on engine components are interchangeable with the earlier design, incidentally.

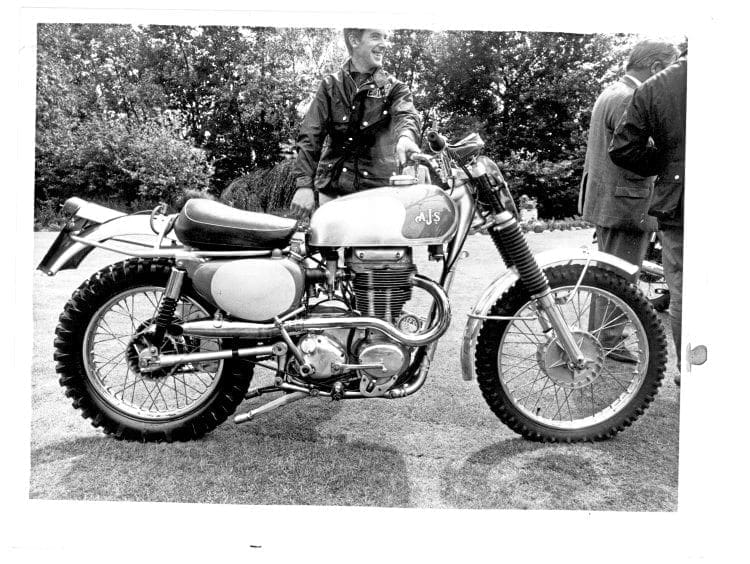

The final Matchless-only big single is worthy of a small mention of its own. Right at the end of their existence, the AMC company produced their final scrambler, the Matchless G85CS. In a final (largely unsuccessful) attempt at stemming the onslaught of European and oriental two-strokes, the Matchless big banger gained a new and very fine chassis indeed. It was apparently based upon a chassis from the Rickman brothers, but worked well for AMC.

The Bicycle

One of the DR riders’ favourite features of the wartime G3L Matchless was its telescopic-forked front end, and the AJS range, along with its Matchless stablemates, entered the brave new peacetime world with this advantage right from the start.

AMC converted the rear end of the rigid frame with which they had launched into the postwar market by simply replacing the triangulated rigid rear chainstays with a subframe to carry the seat and suspension top mounts, along with the addition of a substantial alloy casting to carry the swinging arm pivot, and a selection of tubes to connect the bottom of the alloy casting to the front downtube.

It sounds complicated, and it would probably have worked out cheaper in manufacturing terms to have designed a complete new frame, but cost accountants didn’t run companies in those days.

The early rear spring/damper units were known by the same ‘Teledraulic’ name as the front forks. Unlike most of their opposition, AMC rear suspension was originally built by themselves, and was not bought in from one of the suppliers (Girling, Woodhead-Monroe and Armstrong were suppliers to other motorcycle manufacturers).

The Matchless and AJS swinging arm frame handled well enough, too, with its massive construction making light work of the relatively low power outputs of the time.

The combination of modern roads, modern rubber and limited ground clearance means that even early AMC bicycles can be cranked over until the undercarriage grounds in perfect safety.

Another nice touch is that AMC’s own rear suspension units are as rebuildable as their front forks, and most spares are available.

Although Matchless and AJS twins were only ever available with sprung frames, the singles retained a rigid frame option right through until the appearance of the 1956 line-up, which featured a fairly major across-the-range redesign.

Why the option?

Some experts considered that the rigid frame was better for attachment to a sidecar, while others preferred its simplicity, lighter weight and (slightly) lower cost.

The original sprung back end’s suspension units, which were known latterly as ‘candlesticks’, were superseded in 1951 by the rather more famous ‘jampots’, which were conspicuously fatter than the candlesticks and remained a feature of AJS and Matchless machinery until 1957.

A neat touch of both marques’ machines until 1963 was that they fitted their rear shocks with clevis lower mountings, rather than with the side mountings used by everyone else.

Whether this made a great contribution to their fine handling is open to debate, but it suggested a commitment to engineering excellence that must have helped in the marketing wars if nothing else.

The brakes also underwent incremental improvements from 1946, until by 1956 they were both mounted in handsome full-width alloy drums.

These looked great, and worked adequately by the standards of the day, but dismantling one reveals that the lining area is in fact very small.

Those brakes persisted until 1963, when AMC had something of a brainstorm and introduced redesigned hubs for that year only – usually referred to as the ‘interim hubs’ – and then they followed up for 1964 and the rest of the range’s life by fitting Norton brakes along with forks from the same stable.

And they are the models to ride if you want the best stopping, not least because the Norton Commando’s 2ls brakeplate fits as a direct substitute for the sls original.

The new-for-1963 hubs finally saw the end of the vintage built-up wheel spindle, long a feature of AMC motorcycles. In this design, the wheel spindle comes complete with its bearings.

When replacement is due, the whole assembly needs replacing, rather than just the worn out bearings themselves. Anyone who has rebuilt a push-bike will be familiar with this idea, and its departure was no great loss. Spindles are usually available from spares specialists.

The year-on-year changes to the chassis are too numerous to list here. Significant was the 1957 change from Burman gearboxes (excellent accurate shift, enormous durability, slightly ponderous action) to one of their own design (excellent accurate shift, enormous durability, clean light action), which was fitted across the AJS, Matchless and Norton heavyweight ranges.

Also significant was the redesign of the frame to do away with the curious alloy swinging arm pivot mentioned earlier, although that new-for-’56 frame remained of a basic single-front-downtube type, leaving the final major shift to a duplex cradle until 1960.

Everything else, from toolboxes to mudguards to electrical sundries, underwent the familiar process of steady change, and a dedicated marque history book is the place to discover all of them.

The final change to the heavyweight chassis took place in 1964, when, as mentioned above, the entire ‘Roadholder’ front end from the Norton range was fitted to the AMC frame, along with the Norton rear wheel.

This allowed increased across-the-range standardisation for the company, which was steering well onto the rocks by that time anyway, and produced some strange models: Matchless/AJS singles badged as Nortons (the Norton Model 50 Mk2 and ES2 Mk2, which were AJS Models 16 and 18 respectively), and almost identical twins fitted with Norton engines and badged as everything else (the Norton N15, Matchless G15 and AJS Model 33, in various trims). Some enthusiasts love these latter-day hybrids, others loathe them…

AJS and Matchless heavyweights all offered the traditionally comfortable British ‘sack of spuds’ riding position, handling that improved steadily until the appearance of the final duplex frame, which is very good indeed, and steering and stopping at least on a par with their contemporary competition.

AMC maintained their policy of gradual development of the AJS and Matchless ranges, which has many advantages for the latter-day collector and restorer.

Basically, almost any AJS part can be made to almost fit almost any similar AJS motorcycle, so you should rarely be kept from the road by the unavailability of essential spares. The exactly correct spare may be elusive, but something that fits – and works – will almost certainly be available.

There are still a lot of AMC motorcycles about which run well and look great but which are less than strictly original in their fittings.

Whether this is a good or a bad thing depends upon your own viewpoint, but one of my own reasons for running AMC bikes for two decades was their easily available, almost correct, parts – as well as for their comfort, reliability and fine handling, of course.

Ignoring their obvious modern-day performance limits, AMC singles are fine to ride. They are flexible, mechanically quiet and handsome to look at.

The one to have? Either very early or very late are the ones we’d recommend. The post-64 short-strokers are quick, agile, revvy and rare; the rigid, iron-head 1940s’ versions are the most charming, gentle and – if you like – classic.

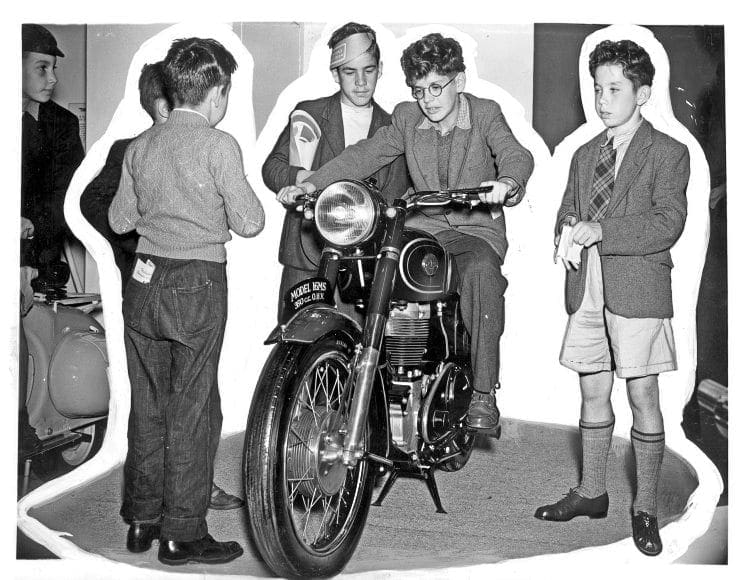

This is a 1957 350

Reliability on today’s roads is generally fairly good, although there were a lot of suspect pattern big-end bearings around for several years, which tarnished the reputation of the 500s, and which still turn up from time to time.

The AJS & Matchless OC is a fine, professional club, and remanufactures most vital spares.

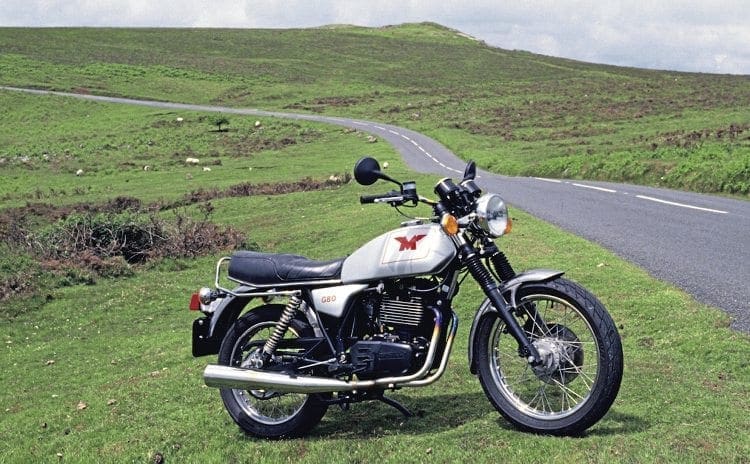

There was an attempt at reviving the old name of Matchless in the late 1980s, by L. F. Harris Ltd. These fine folk, who had been building Triumph Bonnevilles under licence down in Newton Abbot, Devon, built a Rotax-engined 500cc roadster under the ‘Matchless G80’ label.

Although a pleasant enough machine, and welcome in the AJS & Matchless OC, the bike was really too expensive to sell well, and indeed did not.

Such problems as these last singles suffered from were mainly down to poor starting, breaking rear wheel spokes and a sometimes fragile finish. The engine was durable enough, the oil-in-frame bicycle was well-built and fine-steering, while brakes by Brembo and reliable electrics added to an attractive package.

Nomenclature

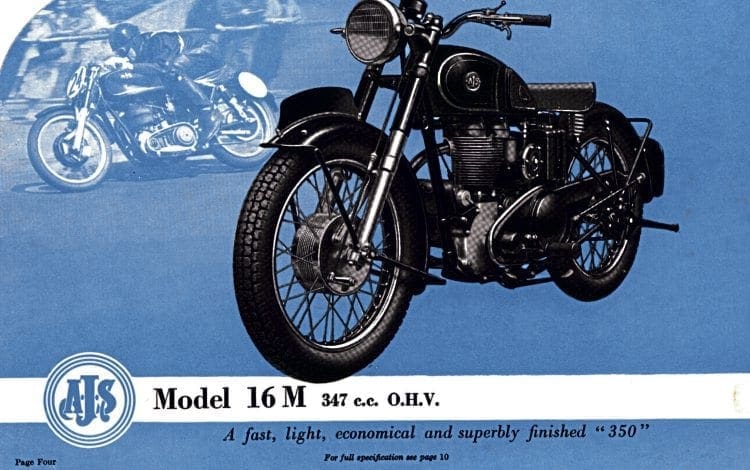

All AJS and Matchless singles can be identified by their engine numbers. Indeed, as we have mentioned already, until the early 1960s when AMC brought a flush of remarkable model names to the market the bikes were best known by their model numbers. So, with the Matchless equivalent in brackets, here is the AJS heavy single range.

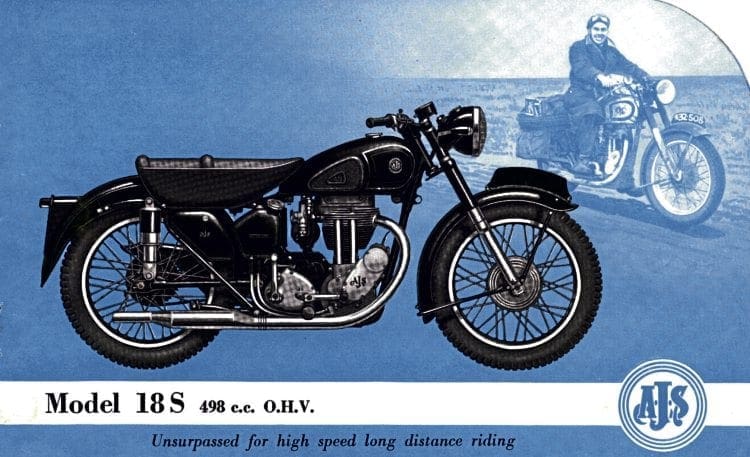

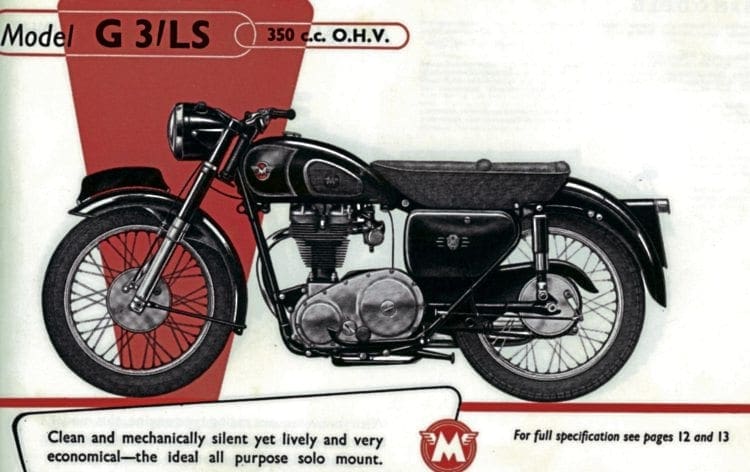

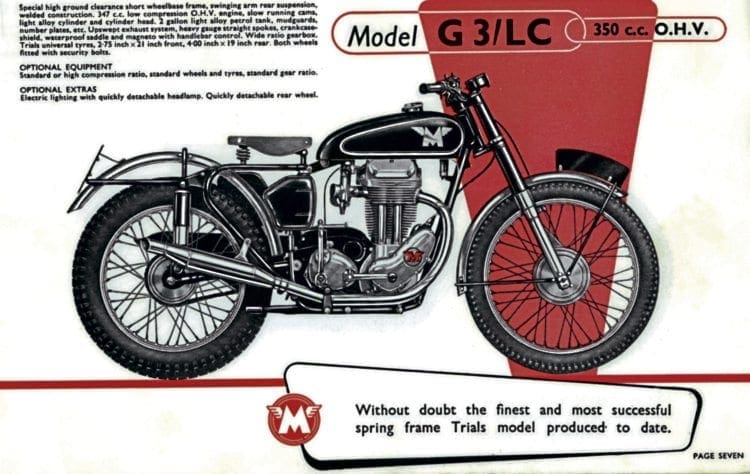

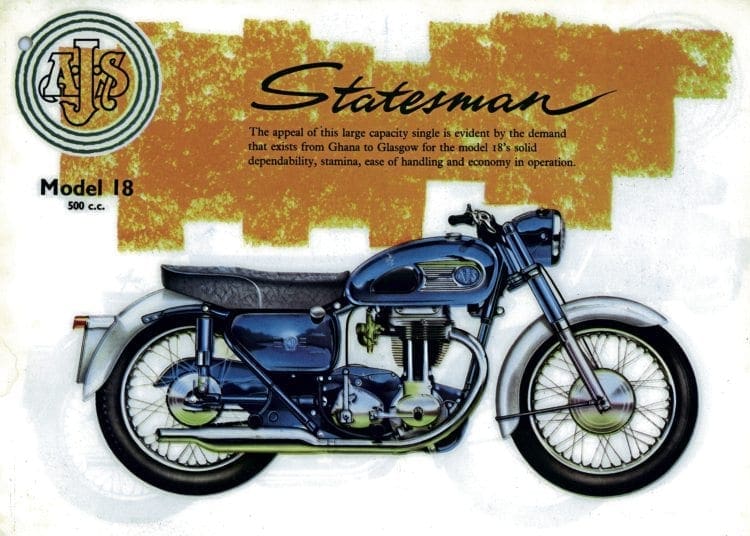

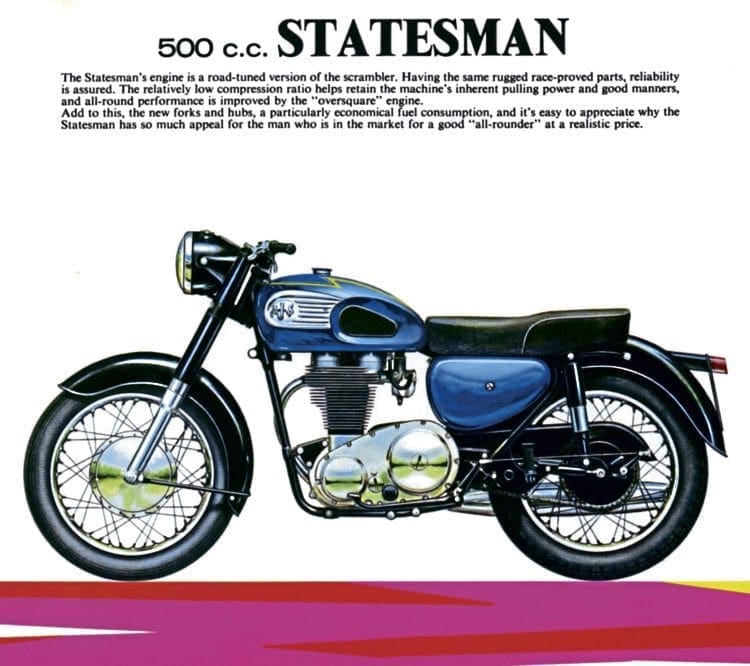

The postwar range began with the 350cc Model 16 (Matchless G3L – L or ‘Light’) and 500cc Model 18 (Matchless G80). When rear springing appeared, the 16 became the 16S (for ‘Sprung’, not ‘Sports’ — do not ever be fooled by this) and the 18 the 18S (Matchless G3LS and G80S).

Competition versions were denoted by the addition of a ‘C’; hence 16C and 18C, followed by the 18CS (Matchless G3CS and G80CS). When rigid roadsters were no longer available, the factory dropped the ‘S’. Thus the 18S went back to being the plain old Model 18. It’s simple really.

There were of course more models than that, but you’re unlikely to find ‘MCS’ or ‘RR’ suffixes (unless you’re very lucky indeed) and only a single single carried the famous AMC ‘CSR’ suffix. If you find one of those – the Matchless G50CSR – tell us at once!

FAULTS & FOIBLES

These genuinely are fairly bomb-proof motorcycles. They were intended – for the most part – to provide years and years of reliable riding to work, and although most enthusiasts are most familiar today with the comp singles, AMC sold a whole lot more road bikes than comp kit.

This is well worth remembering if you’re offered what claims to be an original competition machine. Check with the experts – first stop the AJS & Matchless OC, who hold the factory records.

Early ‘candlestick’ and ‘jampot’ rear suspension is pretty short travel and firm, and the earlier front forks have 1 1⁄8” stanchions rather than the later 1¼” items – all front brakes fitted prior to 1964 can be marginal on modern roads unless carefully set up.

Do not believe the old tale about the tin primary chaincases being impossible to seal. This isn’t true. They were oil-tight when new, and the reason they all leak later is down to ham-fisted assembly.

True up the joint faces on a surface plate, fit all the correct spacers, use modern sealing bands and they won’t leak. Much.

Similarly, the long chrome pushrod tubes will leak if Mr Bodgit has been at them, but they don’t need to.

PEER GROUP

Many manufacturers of the day offered machines with identical intent: simplicity, reliability and comfort for everyday riding. Try a BSA single if you want mainstream, both B31 and B33 are direct equivalents. Royal Enfield built a lot of Bullets in 350 and 500 forms, and they’re recommended.

Norton were part of the AMC stable after 1953, and also offered competing 350 and 500 singles of similarly conventional design; the Model 50 and ES2 being the better known.

However, with their spirit of adventure well to the fore, they also offered a 600cc single in both sidevalve and ohv forms, the Big4 and Model 19, and if you fancy a challenge in the kick-starting department, they come recommended!