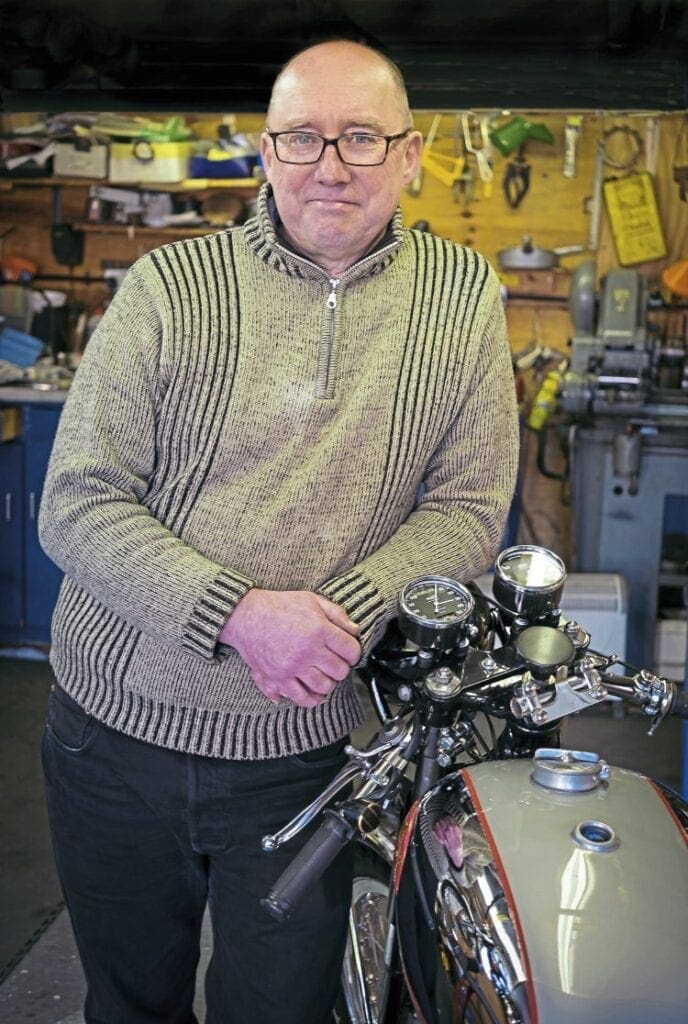

A conversation between Robert Davies from CBG and restorer Peter Collins provides much food for thought for potential rebuilders….

PHOTOS BY Rob and Peter and Robin Horton

BSA’S CLUBMAN GOLD STAR DBD34 (a whole £270 in 1956) was the last, and many say the best, of the Gold Star range. But like a thoroughbred horse, it was highly strung, and could be a pig to get going – so you got two animals for the same price. Oh, come to think of it, the tickover was an unruly creature too.

It is also true to say that BSA had gone as far as it could to get as much power out of this engine, and could see the writing was on the wall as far as big singles were concerned.

Sales were going down and being lost to smoother twins, and as the bike was hand produced, the profit margin was also getting small for the numbers purchased.

Still, testosterone-filled youths who had the readies available were still eager to get their hands on the beast, and it’s the same 50 years later – although those youths are older now.

CBG. So Peter, what got you started with this particular Gold Star rebuild? Are you a masochist, knowing as we do all the problems associated with getting an authentic bike at the right price?

Peter Collins. It’s true, there are a lot of fakes around, and you can be seriously stung if you don’t do your homework.

But I think if you have the desire to achieve something special, and have the patience and resources to carry the task from start to finish, the bike can give a lot of satisfaction.

As we all know, the 500cc Gold Star is probably one of the most prestigious bikes of all time.

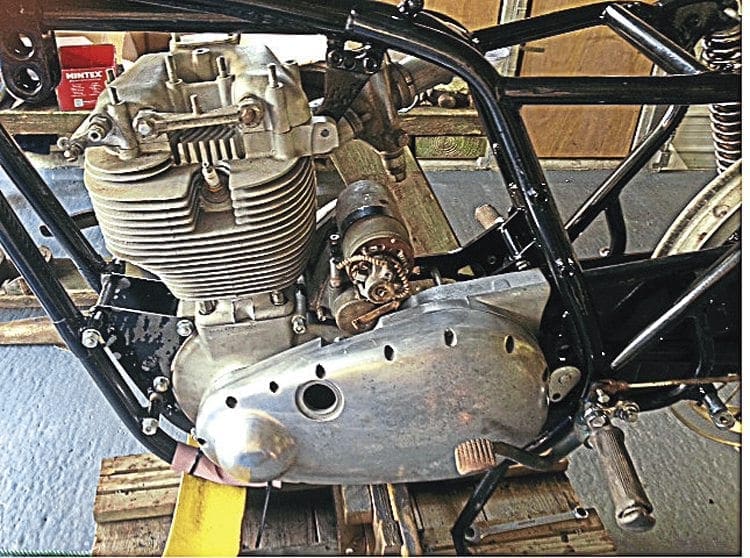

As for provenance, I knew the seller of the bike. I say ‘bike’, but it was in essence two boxes of bits; pretty much a complete bike, but a collection of 60-year-old bits nevertheless.

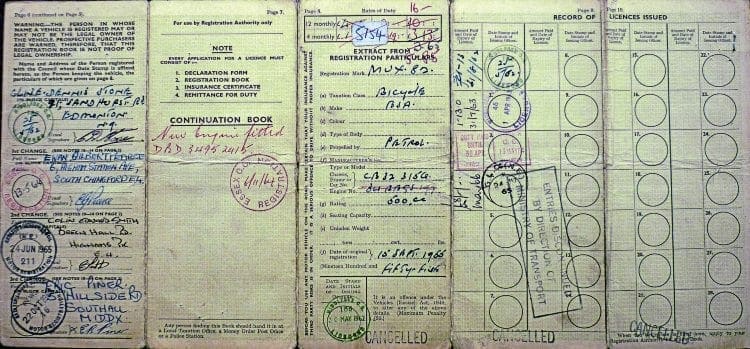

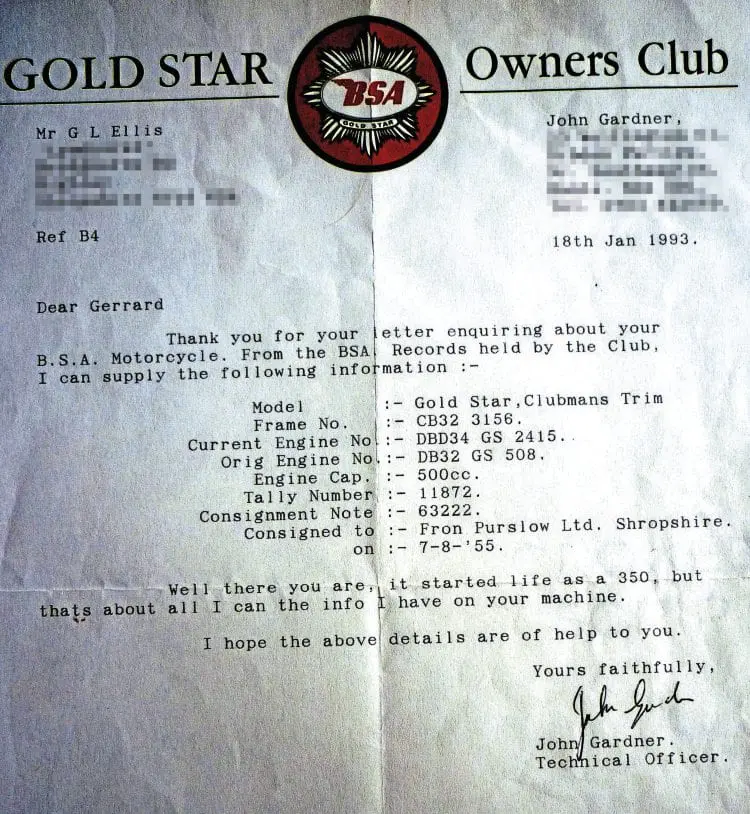

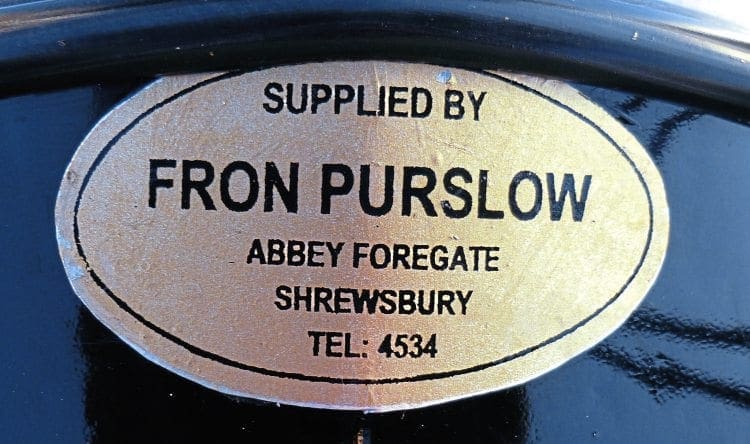

And I knew that it had been in that state for 20 years. The bike was originally a 350, registered CB32 3156.

The engine must have been damaged back in the Sixties because the crankcase date stamps were different, and then later, in 1964, exactly a decade from new, the engine was changed from the original 350 to the present 500cc.

We have to remember that these particular machines were expensive even in their day, being built to order, individually tested, and were often either ridden hard, or raced in events like those at the Isle of Man TT, where in the 1950s they were very successful.

As for my reasons, I was interested in bike rebuilds years ago, before going seriously into classic car restoration, especially the E-Type Jaguar, of which I built several.

But as the years went by, the price of those particular cars went astronomically high, so like a few others, I returned to the fold of motorcycles because they were more affordable. My two boxes of Goldie bits came to £7500 (in 2014).

CBG. So where did you start?

Peter. My first tip is do your research. Get all the printed material available, talk to your experts and join the Gold Star Owners’ club, whose members are always most willing to give their time and expertise.

The next task was to take the bits out of the boxes and do an assembly to check how things fitted together, and to see what – if anything – was missing.

My second piece of advice is to take nothing for granted, and get every part checked out, either by using your own expertise or that of someone more knowledgeable. So I approached one of the most well known experts, Phil Pearson, regarding the crank, conrod and piston, all of which needed replacing.

The crank took six weeks to produce and cost £800, while the new piston was £200, and the crank was balanced along with the piston for smooth running.

The barrel was bored out to 40 thou, and the same company fitted new valve guides and valves. The rebore was undertaken on the same day that I picked up the crank and piston.

One odd thing about the Gold Star is the fitting of the cylinder head gasket, and you need to be careful to have the genuine article. First, the head is bolted down onto the barrel, and the gap between the two is measured very carefully.

If I recall correctly, the gap on my engine was 37 thou. The head is then taken off, the gasket applied and layers are taken away until it is exactly five thou above that reading – so in this case the gasket need to be 42 thou thick.

This is just one of the small details that needs to be done properly if you are ever going to get any real satisfaction from the engine, and keep oil from coming out of the pushrod tube.

Another improvement from Phil was a metal plate fitted to keep oil from escaping from the primary chaincase.

The old method was to use a sort of boss with a scrolling section that was designed to push oil back into the chaincase, but that didn’t work too well.

And if you are spending thousands on the rebuild, why spoil a ship for a ha’p’orth of tar – as they say.

Meanwhile, I was stripping the magneto and dynamo, and getting the frame off to be shotblasted and powder coated (Redditch Shotblasting).

Black Cat, of Dudley, took the original hubs and laced Italian Borrani alloy rims on with stainless steel spokes.

The hub was an original 190, painted of course, but I had to put it on the lathe to take it back to a true circle before fitting new shoes.

Some restorers have polished their front hubs back to an alloy shine, but originally, as I say, they were painted. Black Cat also did a lot of the aluminium polishing on the engine casings.

CBG. And the suspension?

Peter. Again the suspension, front and rear, was stripped and rebuilt using new seals.

CBG. Goldie gearboxes came in a wide range didn’t they? Were there any problems with that?

Peter. There were two gearboxes with the bike, the racing RRT2, and an RR. I decided to go with the former, but that required stripping too.

By the way, the RR stood for Ultra Close ratio, while the T stood for Torrington needle roller bearings –and there were two of them to take the strain from the engine.

When I had it apart, I saw that the mainshaft was in a poor state, so Chris Williams, of Netherton, replaced that – more money. A lot of British bikes had a keyway system to fit cogs to shafts, and it was the keyway that had gone. It’s not a great mechanical system, but that was the way it was done.

As for bearings, I got most of them from Pat Arnold, of Stourport, who also supplied seals, gaskets and stickers for the toolbox and oil tank.

The rear hub sprocket teeth were worn, so in the end I turned away the old teeth on my lathe and tightly fitted a new sprocket that was keyed in by small grub screws.

CBG. I see what you mean about connections. What about electroplating?

Peter. By this time I had a nice box of nuts, bolts, spindles and other parts that required replating, and I recommend that if you ever do this, you either take an inventory of all the parts, or to be even quicker, just take a photo of everything.

That way, if the chrome platers you decide to use lose a part – heaven forbid, they wouldn’t do that, would they? – then you have the proof that you took it in.

The steel tank had some dents in it, so before that could be chromed and painted, I had to get a specialist to take the dents out.

And before I could get the tank painted, I had to find another genuine article to make detailed drawings of where the paintwork and the coachlines came to. All very time consuming but absorbing nevertheless.

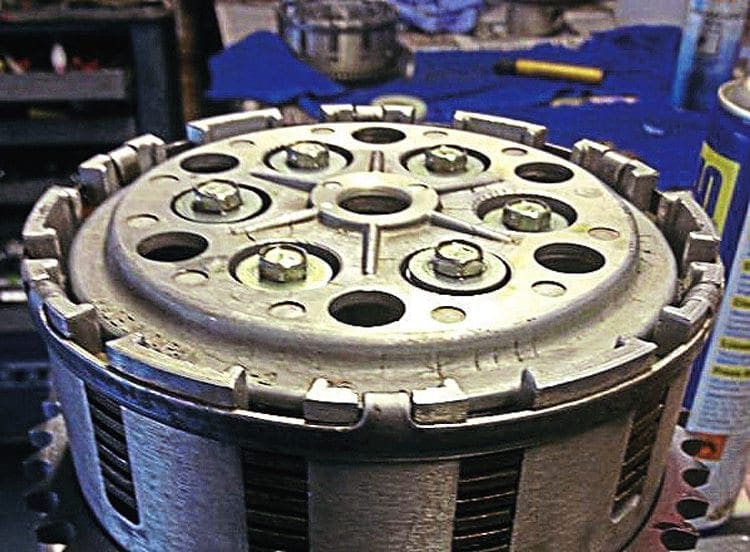

CBG. Now I don’t wish to upset Gold Star owners, but I believe it’s true to say that the clutch of the Goldie had a bit of a reputation for not being that good?

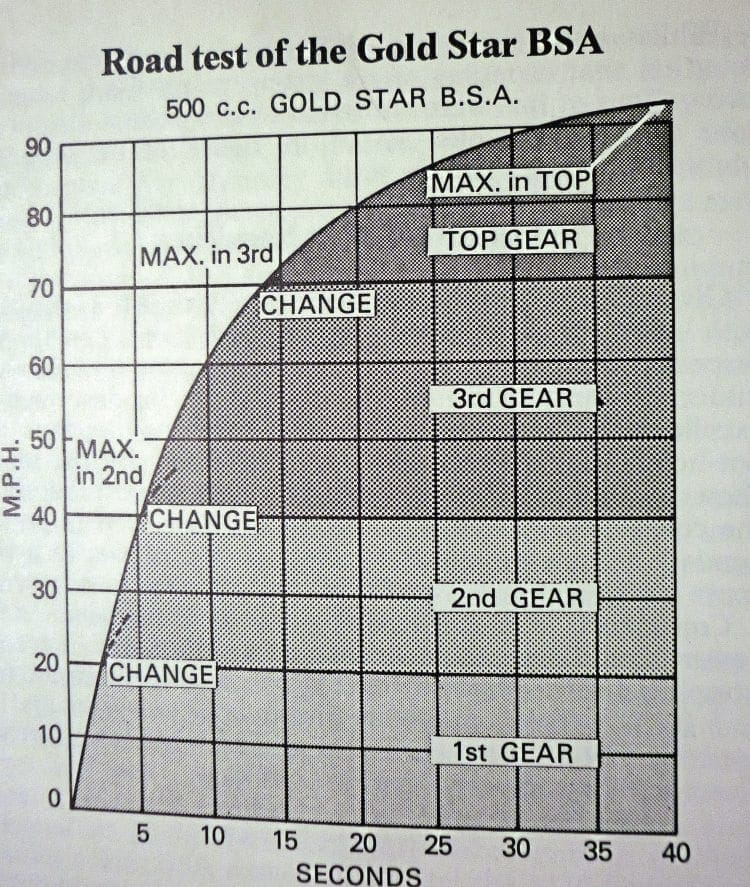

Peter. It’s true that with a high first gear, there was always a lot of clutch slipping required to get going.

I saw that Phil Pearson had used a Suzuki GS550 clutch on his Gold Star, so I decided to do something similar with my own.

I already had a Suzuki clutch, so I bored out the inner clutch basket on the lathe, and adapted the Triumph clutch basket by turning the side walls down so that it could then be bolted onto the inner Suzuki clutch.

CBG. How far did you go in the goal of originality? There are a lot of so-called experts out there that love to pick faults with any rebuild. And what about the electrical system?

Peter. My goal was to keep the bike as original as possible, but there is no way out of using new parts, such as the piston and crank in this case.

As for authenticity for instance, the original GP 1½in Amal carburettor is polished on many machines, but the original was painted a sort of pale sandy green colour, so in all instances I have tried to be as true to the original design as is reasonable.

You can, of course, fit modern electronic ignition to old bikes, but that was a step too far for me, even though this does make a vast improvement to reliability.

As for the electrical system, it’s not that complicated, so I sorted all the new wiring and fitments from Autosparks online and that was that.

The 60-year-old clocks, speedo and rev counter, driven by cables, took a little more tender care.

Fortunately, an old mate of mine, Kevin Bishop, is a dab hand with these, being trained in the ancient art by his father before him.

He took them apart, remade the faces to exact specification, and cleaned them before reassembly. I have to admit that the rev counter is not from a Goldie, but from a Royal Enfield, so again the face had to be made to match the BSA standard item.

CBG. And then came the great day for starting the engine.

Peter. Always a time of excitement and due trepidation. So I went through the starting procedure, and – nothing happened – it just wouldn’t fire up, and there is only so much kick-starting you can do before you have had enough.

So I rang Phil Pearson, who asked if I had utilised the valve lifter, and I had to admit that I hadn’t yet fitted it; I didn’t think that it was required to get the engine going, and this is where expert advice is always necessary. Apparently, the valve lifter takes away some of the compression so that one kick will get the engine turning over fast enough get a useful spark.

Poor spark and no start. Another adviser suggested that I swap the 21-tooth engine sprocket for a slightly smaller 19 tooth.

This also allows for a faster engine turnover. Starting a Goldie was never fun from cold, but was sometimes even worse when hot, due to the heat in the magneto, but that’s just one of the ‘fun’ things about a classic bike.

CBG. So Peter, in conclusion, how long did the restoration take, what are the benefits of owning a classic machine, and how much did it cost?

Peter. Mmm, well; it took about 10 months to get the bike from its bits in a pair of boxes stage into a glamorous and rideable state; and about £6500.

The advantages of a pre-1960s bike are that there is no MoT and no road tax. And as an investment, it’s better than money in the bank – at the moment – and of course there is the immense satisfaction of having it as what I like to call my Garage Princess.

CBG. Really good reasons. And finally; what is it like to ride?

Peter. Horrible! You get that great feeling of riding a piece of British history, but the riding position is – how shall I put it – an acquired taste, and the low down clip-ons kill your wrists.

Having said that, once the carburettor and ignition are working in harmony, it is pretty fabulous on a glorious afternoon to go for a ride and show it off at the local bikers’ hangout.

Of course, if you wish to do some serious posing, it’s best to have the starting procedure right before you have to perform on it in front of dozens of judgmental eyes.

Star turns

So, how did BSA motorcycles operate its Star rating? The Gold Star Book by Bruce Main-Smith reveals that in 1927, the vertical single, the gentlemanly Sloper – not the catchiest of names for a bike – turned out 18bhp and sold well (80,000 is the number quoted).

So BSA wisely decided to make a hotter version that churned out a more respectable 24bhp at 5200 revs.

This bike was dubbed the Red Star Sloper – the name’s getting better at least – and from then on, whenever a more tuned version of a bike was introduced, a Star rating was added.

A true evolution followed with the Blue Stars and Silver Stars until the 1937 season when an Empire Star was hotted up and, in the capable hands of the late Wal Handley, and running on methanol, it achieved 107.57mph at Brooklands.

Mr Handley was presented with the traditional gold star pin to celebrate the feat, and BSA promptly renamed its most sporting single as the Gold Star. A legend was born.

Read more News and Features online at www.classicbikeguide.com and in the latest issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!