In a large shed at Kitts Green, a few miles from Birmingham city centre, Dennis Poore assembled a team to try and save the British motorcycle industry.

WORDS BY Tim Britton PHOTOS BY Bob Clarke

BY THE TIME this prototype four-cylinder Trident- based machine superbike sneaked out of the experimental department at Kitts Green the British motorcycle industry had had it.

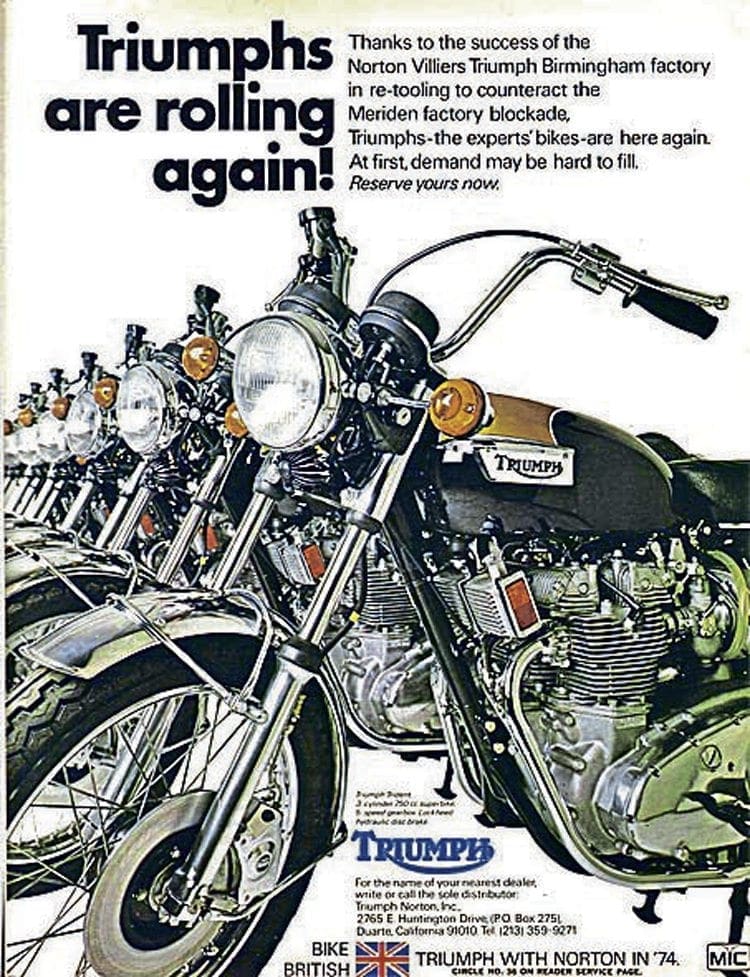

Yes, in 1974 the all-encompassing motorcycle industry in the UK was down to a handful of people grouped together by Manganese Bronze top lad Dennis Poore.

Running under the mantle Norton Villiers Triumph, or NVT, Poore was attempting to salvage something out of the chaos and produce a viable company with its eye on the future.

That this was to be Norton based – and what happened when Triumph found this out – has been the subject of much writing over the past 40-odd years and is not within the remit of this piece.

The inescapable fact is by the mid-60s investment in the industry was woefully inadequate, designs were outdated and the end was coming.

There were those who realised this and tried to do something about it; the BSA/Triumph triple project was one such stopgap idea.

It fitted the bill, but almost on the eve of its launch Honda brought out the CB750/4, which bristled with exotica such as four cylinders, an overhead cam, disc brakes and much more. Next to it the Trident looked basic.

In reality the triple from BSA/Triumph should have been on the drawing board by the end of the 1950s, launched mid-60s and its successor ready for the 70s.

Instead, with Poore well aware of the fickle market, he slipped the casual comment into discussion with his experimental team over their projects that what was needed was a four.

When the Kitts Green team – headed by Doug Hele and including Jack Shemans, Les Williams, Arthur Jakeman, John Barton and Ron and Alan Barratt – thought about it they felt that an engine could be ‘mocked up from triple parts’ as a design exercise.

When Poore paid his next visit to Kitts Green and mentioned the four idea again he was apparently gobsmacked to find Hele’s team had created one.

Make no mistake about it, even the team involved in this one-off project referred to it as either a lash-up or bodge-job, but that glosses over there being the sort of lash-up and bodge-job completed by unskilled and technically unqualified amateurs in a dimly lit shed and the sort of lash-up and bodge-job created by skilled craftsmen with years of experience and ability to call on.

So, creating a four-cylinder Triumph engine is not just a simple matter of taking two triple engines, knocking a cylinder off each and welding the lot together then slipping the result into a frame with some fancy engine plates.

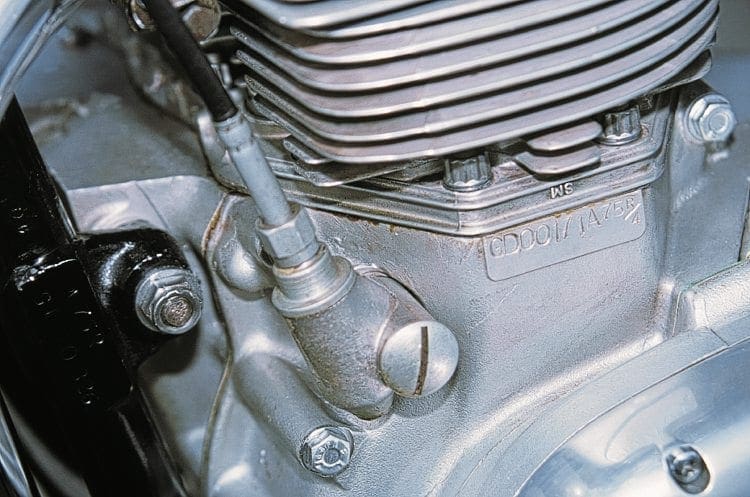

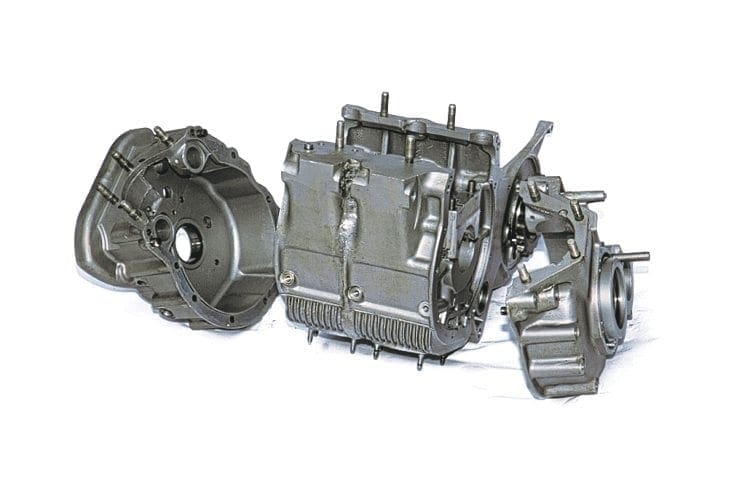

The Triumph triple engine crankcase casting is typical of the British industry in that it’s constructed of three sections split vertically and bolted together, with the timing side and primary drive bolted on to either side.

In order to widen the engine for another crank journal and a wider barrel, two centre sections were modified to achieve the correct size.

One problem was that the crankcase had a number of oilways which couldn’t be sealed properly.

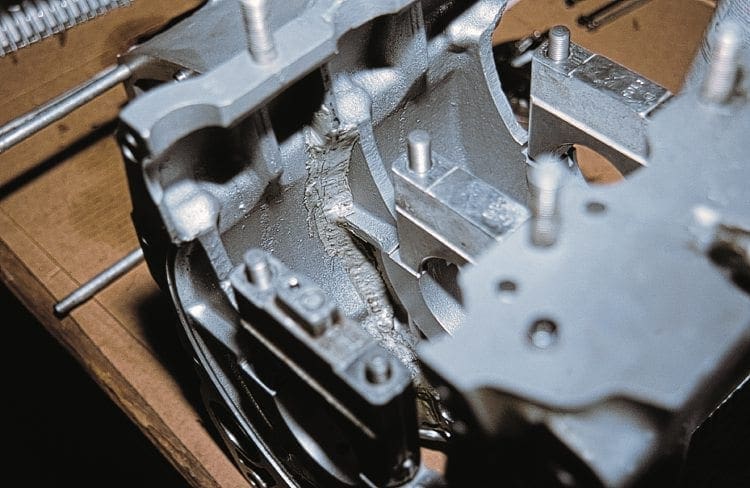

This is where Devcon F comes in, at the time this epoxy resin-based casting material was popular among people involved in just such an exercise as Hele’s team.

When this unique motorcycle was refurbished for the National Motorcycle Museum 14 years ago CBG was lucky enough to be invited along to the initial inspection of the components as it was pulled apart.

Also present on that day were several members of the original team, including Jack Shemans. As the motor was pulled apart Jack told us how the epoxy material was forced into the oil galleries to seal them.

Mandrels were made to the exact size required and coated with Devcon F; they were then forced into the oilways, which sealed any openings. The material was still in place and sound nearly 30 years on.

Extending the crankshaft was equally involved, with male and female tapers, datum rods to line things up and so, realising they’d only get one shot at doing it right, they rehearsed the procedure in the same way that GP mechanics practice tasks until they’re perfect at it.

Some bits went into a fridge, other bits went into an oven, the whole lot was pressed together and when cool it spun freely in the cases, much to the relief of all concerned.

Initially, camshaft design caused no end of head scratching, and early thoughts centred around welding a pair up were dismissed as impracticable.

Luckily, the Birmingham area had a lot of talented people connected to the engineering and motorcycle world then, probably still does now, so word was sent out to Ray Hyde – Norman’s dad – and a talented machinist.

“Ray, machine us a set of cams, will you, mate”? and back came a pair of four lobe cams a few days later.

After all this, Jack Shemans reckoned that persuading a set of barrels to take another piston and cam follower set was easy peasy… maybe easy peasy for him!

Creating a cylinder head was relatively simple, and it was two heads really, but the rockerboxes took a bit more thought. Shemans cut up four of them to get the required layout, sealed the ends with cardboard and Devcon F, which he held into place until it set. The cardboard is still there…

After seeing the motor on the bench, Poore sanctioned it to be fitted to a chassis to try it out.

A spare frame was on hand, originally destined for an ohc project, and it was altered to widen it on the timing side.

This kept the chain line correct, but the engine overhung the rails by a good way, making it look lopsided from the top.

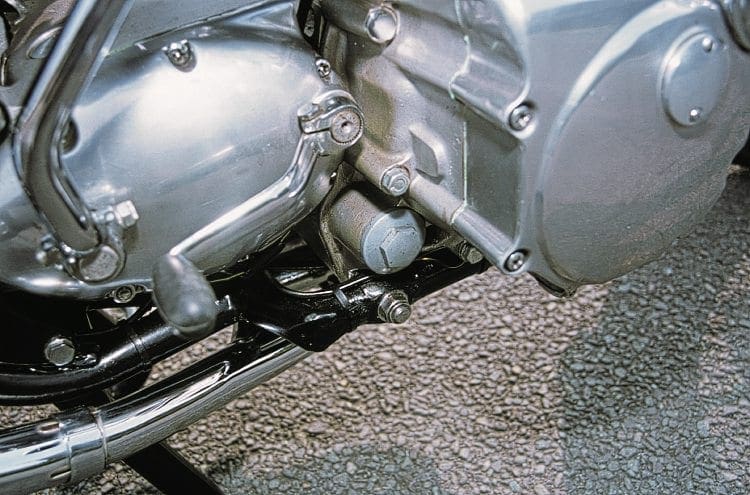

In fact the overhang prevents traditional footrests and foot controls being fitted, so more rearset rests had to be used.

It was also tight around the foot area for those of us with size 11 boots. In this respect alone it is clear why this particular machine couldn’t have saved the industry, but it is equally clear that it could have led to something which might have.

For the rest of the running gear a raid on the Rocket 3 and Trident parts bins produced a remarkably good-looking machine, considering its construction method.

Though quite a number of NVT people had ridden the Quadrent in its day, no one could recall it ever having been officially developed, and the whole team was anxious that it should be understood that this was never intended to be a production bike but merely an evaluation exercise. As such it provided valuable feedback.

Nor was it ever intended to be ridden by outsiders, though MotorCycle’s Midlands editor Bob Currie was probably ranked as part of the industry and did take the Quadrent for a spin before it was lost to view.

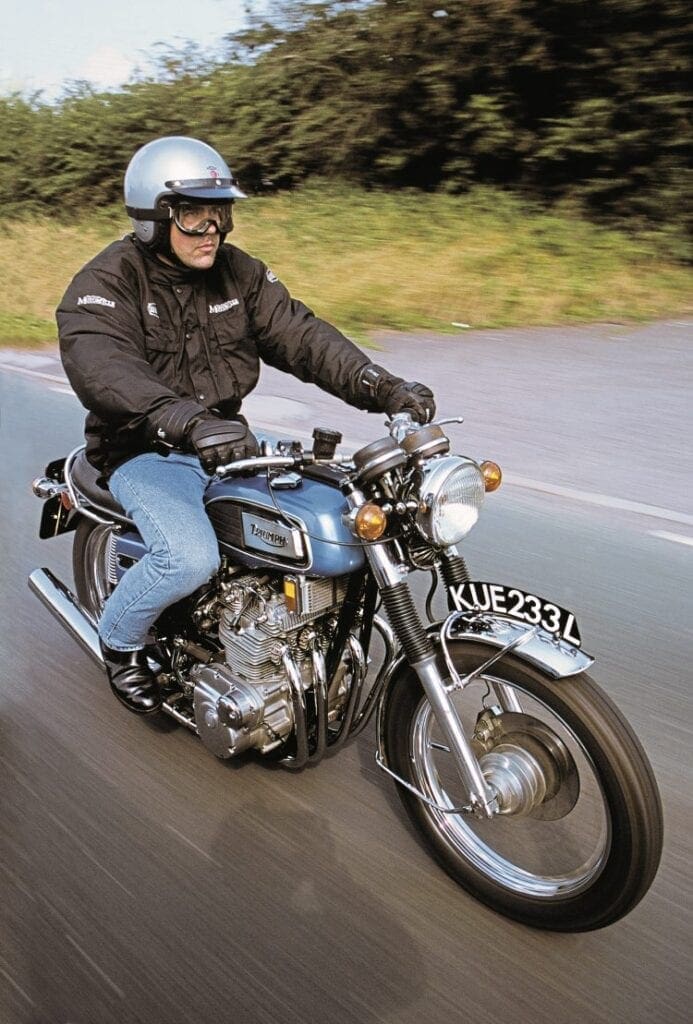

Once the Quadrent was resurrected from static display in the National Motorcycle Museum to become a working machine, I got the chance to be the second journalist to ride it.

Like Bob Currie before me, I was well aware this was not even really a production test bike. The TR3OC-led team implored me to keep an eye on the oil light: “If it comes on, stop, immediately.

“We’ll pay the fine if you’re somewhere you shouldn’t stop.” Thankfully this help wasn’t needed and the Quadrent behaved itself – once I got the hang of the clutch, anyway.

Rumbling my way around the roads near the museum in Bickenhill the potential of this project was clear.

Despite it being a lowly pushrod motor compared to the oppositions’ ohc, there was performance a-plenty, the suspension worked well and there was clearly stopping power enough for the heavyweight machine. If only there’d been a budget at Kitts Green…

PRICE GUIDE

Quadrent – no chance, Trident £6000-£9000

FAULTS & FOIBLES

As a development bike there are a number of interesting areas… it’s bloomin’ wide, bloomin’ heavy and bloomin’ impressive. Oil galleries are made up from epoxy casting material. Clutch is interesting.

ALSO CONSIDER

Fancy a four? You might want to look at the CB750 Honda, equally classic, equally quaint now and much more available. Or how about an Ariel Square Four if you need to remain British? Or buy a Trident…

Specialist info

triplesrule.com

Carl Rosner

carlrosner.co.uk

LP Williams

triumph-spares.co.uk

OWNERS’ CLUB

tr3oc.com

BUY IT NOW

You’ll only be able to buy a four-cylinder Quadrent in a parallel universe, but in this reality there’s plenty of decent three-cylinder Tridents on offer. This 1974 five-speed T150V has just been repatriated and recommissioned, comes with NOVA docs ready for registration, from Totnes Classic Motorcycles for £6495

MANUFACTURED: 1974 ENGINE: Air-cooled ohv in-line four BORE / STROKE: 67mm x 70mm CAPACITY: 987cc POWER: Not available PRIMARY DRIVE: Triplex primary chain, diaphragm clutch ELECTRICS: Points and condenser, Lucas alternator 12V system FRAME: Modified Rocket 3 all-welded cradle FRONT SUSPENSION: Telescopic oil-damped forks REAR SUSPENSION: Girling sealed units controlling a swinging arm FRONT BRAKES: 10in disc REAR BRAKE: 7in drum FRONT TYRE: 4.10in x 19in REAR TYRE: 4.10in x 19in WHEELBASE: 60in WEIGHT: 530lb (approx.) TOP SPEED: 125mph (est)

Read more News and Features online at www.classicbikeguide.com and in the latest issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!