Panther owners are an eclectic bunch. Take the owners' club stand at the Bristol Show for example. Next door, the Vincent OC, all precision, conformity and spit ’n’ polish. On the Panther stand, a double adult combo, two rare and immaculate pre-war Model 95s, and the ‘Panbeam’ – an intriguing amalgamation of Panther engine, Sunbeam frame, BSA bits and AMC pieces finished to a standard that would have merited ‘Best Paint’ at any custom show. I met Simon Gisborne among them to hear his story.

“My father was an aero engineer – at Douglas in Bristol, and at Fraser Nash & Parnell, in Yate, working on turrets for Lancaster and Sunderland. My great-great grandfather worked for Brunel, first track-laying, then building Paddington Station and Crystal Palace. I was working on the family car, grinding-in valves etc at an early age, then fiddling with old motorcycles as I got older. I trained as an electrical engineer, but I realised it wasn’t for me. I went to teacher training college where one of the tutors was a silversmith, something that really interested me, so I developed two parallel careers, one as a tutor and one as a goldsmith. It’s engineering in miniature. There’s not much metal in a gemstone setting; it’s about holding the stone securely but unobtrusively.

I had a Panther outfit when I first started work. One winter, there was thick snow and I offered an apprentice a lift, so he hopped on the back and we set off. Immediately the outfit spun in a complete circle – he screamed and I hung on to the bars hoping it would correct itself, but it just kept spinning and I found I could control it. We went all the way down the road like that, spinning round, and in the end he was laughing at the exhilaration of it all. I had other bikes, Velocette, AJS, Francis-Barnett and Suzuki. I even had a Rudge 350 with a four-valve head – it was a time when old bikes were cheap and easy to come by. I actually bought a Golden Flash just for the sidecar for the AJS. I had some great times with the Panther and they stuck in my mind – and I like the look of that engine – it’s sculpture on wheels.”

I had a Panther outfit when I first started work. One winter, there was thick snow and I offered an apprentice a lift, so he hopped on the back and we set off. Immediately the outfit spun in a complete circle – he screamed and I hung on to the bars hoping it would correct itself, but it just kept spinning and I found I could control it. We went all the way down the road like that, spinning round, and in the end he was laughing at the exhilaration of it all. I had other bikes, Velocette, AJS, Francis-Barnett and Suzuki. I even had a Rudge 350 with a four-valve head – it was a time when old bikes were cheap and easy to come by. I actually bought a Golden Flash just for the sidecar for the AJS. I had some great times with the Panther and they stuck in my mind – and I like the look of that engine – it’s sculpture on wheels.”

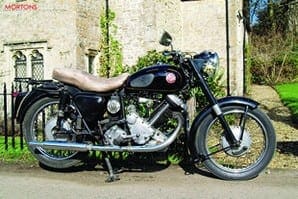

So, around 15 years ago, Simon decided to get another Panther. Conversations with a Velocette owning neighbour, well up on the classic scene, convinced him that the bike would have to be a runner, not a basket case, and as money was limited, he set himself a ceiling price of £1500. This time he wanted a solo and he wanted á suspension. Soon the neighbour was at his door, clutching a copy of Old Bike Mart, in which there was a 1956 600cc Panther Model 100 for sale. It was shabby, but was a runner and £1400. It was in Halifax – 240 miles away. It was in an underground garage with six other machines. They were smart; the Panther wasn’t. The seller had rescued it from a scrapyard intending to restore it, but lost interest. Standing outdoors for years had done it no favours but nothing was rotten and everything seemed present. The only thing not right was the seat, but even that looked robust in a comfy sort of way. What the heck, the tyres had air in them and the engine ran – and it was £100 inside the budget. Simon had found his bike!

Things seldom go quite that smoothly and, as Simon soon discovered, bikes are not in scrapyards for no reason. The hotter the engine became, the noisier it became, so Simon lifted the head and barrel to see what was what.

Things seldom go quite that smoothly and, as Simon soon discovered, bikes are not in scrapyards for no reason. The hotter the engine became, the noisier it became, so Simon lifted the head and barrel to see what was what.

The culprit was a worn big-end bearing. The rollers (two rows, running uncaged between two flanges on the crankpin) had worn on their outside edges, allowing the con-rod to twist enough for the front and rear edges to hit the inside edges of the flywheels. Fortunately, he had joined the owners' club and they supplied a new bearing which the neighbour had fitted.

More worrying was the cylinder head; the fins were badly corroded and the external threads on the exhaust stubs had all but rusted away. It was virtually useless and the repair cost didn’t bear thinking about. Fortunately, a club contact had not one, but three brand new heads.

With original budget out the window, Simon invested in a new stainless pushrod tube, a pair of stainless U-bolts that hold the crankcase, cylinder and head together, and a set of piston rings. Panthers are notoriously heavy on oil and this one was smoking. Normally new rings should have made some improvement, but the engine still smoked. Clearly, the bore was as worn as the big end.

With original budget out the window, Simon invested in a new stainless pushrod tube, a pair of stainless U-bolts that hold the crankcase, cylinder and head together, and a set of piston rings. Panthers are notoriously heavy on oil and this one was smoking. Normally new rings should have made some improvement, but the engine still smoked. Clearly, the bore was as worn as the big end.

Now, original Hepolite split-skirt pistons are still available, but they were made in the days when high oil consumption was an acceptable adjunct to running a Panther. The engines were, after all, slow running, heavy sloggers, happiest when hauling an over-loaded sidecar over the Pennines – which is what they were designed for.

In the early 1930s, the over-riding concern was reducing fuel consumption. There was no doubt that the engine was up to the task, and if it burned a pint or two of oil in the process, so what. However, times change and Simon was aware that a piston from a Volvo or a Rover, with a modern, three-piece oil control ring, had high oil consumption licked. The problem was, nobody could remember which engine. Simon took his cylinder and old piston to Price Bros, an engineering company in Avonmouth, Bristol, and they matched a Volvo piston and bored the cylinder to suit. The engine went back together without a hitch and now oil consumption is no more, but Simon is still none the wiser as to which piston to use.

That left one little niggle. On the open road the Panther loped along happily at any speed up to 65mph, but around town throttle response was poor. Simon deduced the culprit was a worn carburettor, which was more of a problem ten years ago, before Amal carbs were back in production. However, for the neighbour this was no problem – years ago he had been a grass-tracker – and from the depths of his shed he produced a good-as-new Monobloc of exactly the right size. The only thing to change were the needle and jets because his bikes had run on dope, while the Panther has to make do with low octane unleaded.

That left one little niggle. On the open road the Panther loped along happily at any speed up to 65mph, but around town throttle response was poor. Simon deduced the culprit was a worn carburettor, which was more of a problem ten years ago, before Amal carbs were back in production. However, for the neighbour this was no problem – years ago he had been a grass-tracker – and from the depths of his shed he produced a good-as-new Monobloc of exactly the right size. The only thing to change were the needle and jets because his bikes had run on dope, while the Panther has to make do with low octane unleaded.

By chance, his 1956 Model 100 represents what many regard as the pinnacle of development of the heavyweight single. Introduced in 1954, the combination of P&M’s own oil-damped telescopic forks and a swinging arm frame with Armstrong shock absorbers, made for a stable and comfortable ride. New for 1956 were the standardised 19in wheels incorporating eight inch brakes, a serious improvement over earlier machines and easily a match for any contemporary single leading shoe brake. Incidentally, like Ural today, Panther-produced sidecars fitted the same wheel and brake, so if a spare was carried it could serve any of the three.

In marked contrast, the engine remained unchanged since the introduction of enclosed valve gear in 1938. The second edition of Pitman’s Book of the Panther, published in 1958, carries a cut-away illustration of the 1935 engine with the note that ‘subsequent engines are fundamentally similar’. The only obvious difference is the substitution of a Lucas Magdyno, at the rear of the crankcase, in place of the original separate magneto and frame mounted dynamo. To condemn the engine as archaic is to ignore the unique appeal of the Panther; if P & M had added an additional cylinder, placed them upright in a cradle frame it wouldn’t have been a Panther as we know it.

In marked contrast, the engine remained unchanged since the introduction of enclosed valve gear in 1938. The second edition of Pitman’s Book of the Panther, published in 1958, carries a cut-away illustration of the 1935 engine with the note that ‘subsequent engines are fundamentally similar’. The only obvious difference is the substitution of a Lucas Magdyno, at the rear of the crankcase, in place of the original separate magneto and frame mounted dynamo. To condemn the engine as archaic is to ignore the unique appeal of the Panther; if P & M had added an additional cylinder, placed them upright in a cradle frame it wouldn’t have been a Panther as we know it.

Simon uses the Panther for daily transport in good weather and has been known to cover some serious miles when the weather has not been so good. Like the time he went to the Owners' Club National Rally in Yorkshire. He reached Stafford before the rain set in and a misfire developed, reducing his top speed to 45mph – but he kept going because sometimes these things fix themselves. The weather was still bad for the return trip, and, on uphill stretches of the motorway it was all he could do to coax 25mph out of the bike. Nine hours to get home, soaked and ready to drop.

The magneto was in dire need of attention. His local shop, Weymouth Motor Cycles in Frome, Somerset, a traditional establishment with an oil-stained wooden floor and a proprietor named Nobby Clark overhauled it and it’s been sparking happily ever since. They also fitted a new armature in the dynamo. In all other respects the electrics were sound, so Simon chose to stick with the original six volt system, just plugging a halogen bulb into the headlight as a concession to modernity.

Then there was the time he was on a run up the Severn Valley when he felt something odd with the steering. He pulled in to discover that the nut had come off the rear wheel spindle. Pre mobile phones, when breaking-down in the middle of nowhere meant a long walk. Simon chose to walk back the way he had come, on the slim chance that he might find the nut, but instead he found a cottage, with a phone. When a breakdown truck arrived, the driver looked at the bike, delved into his toolbox and pulled out a nut that matched the spindle. How’s that for luck?

Then there was the time he was on a run up the Severn Valley when he felt something odd with the steering. He pulled in to discover that the nut had come off the rear wheel spindle. Pre mobile phones, when breaking-down in the middle of nowhere meant a long walk. Simon chose to walk back the way he had come, on the slim chance that he might find the nut, but instead he found a cottage, with a phone. When a breakdown truck arrived, the driver looked at the bike, delved into his toolbox and pulled out a nut that matched the spindle. How’s that for luck?

When asked what he likes most about his Panther, he says: “Here’s something you don’t find on other bikes. On the back of the timing case, just above a number, is a letter. On my bike it’s a letter ‘W’ and according to the factory records that means that a chap named J. Wilkinson built this engine. How’s that for a personal link with the past? I shan’t restore it, I think it’s more important to preserve it in its original condition. Repair it when necessary, obviously, but keep it on the road.” ![]()