Some years ago, while on the Ponthir British Club’s annual Brecon Run, I spotted a very smart Royal Enfield Constellation. This one was handsome but it also carried an Ontario number plate. That’s not a suburb of Cardiff, you know, it’s a province of Canada, home of many big British bikes of the 1960s. I assumed it was the original plate, the Prodigal Son back home at last.

Fast forward a dozen years. The phone rings and a voice says: “My name’s David Williams, you’ll not remember, but we met on a Ponthir Club run. I was on my Constellation. I’ve just restored it in Clubman’s trim, like in the 1960 catalogue, and wondered if it would suit Classic Bike Guide?” Silly question.

With respect to today’s Royal Enfield and their 500cc singles, a 700cc Redditch built twin is a totally different piece of kit.

David’s instructions emphasised that photographer Wilkinson and I should follow our sat navs to find his place. Now, I’m an old fart who can read a map and take directions, but doesn’t have a little talking box to take me to my destination via deep fords, impassable field roads and ferries that cater only for foot passengers.

David’s instructions emphasised that photographer Wilkinson and I should follow our sat navs to find his place. Now, I’m an old fart who can read a map and take directions, but doesn’t have a little talking box to take me to my destination via deep fords, impassable field roads and ferries that cater only for foot passengers.

OK, so I’m out of date but I can show you a country lane sign warning HGVs that the Severn ferry ahead is for foot passengers only and the narrow stonewalled lane where a Volvo monster followed instructions to a local factory. A 40 footer and a right-angled turn into another lane didn’t work, and on reversing, over went a length of ancient stonework. What works on a Business Park might not in the sticks.

I printed some maps, swallowed an Optimistic Pill and headed for South Wales.

It took one stop to ask where this road was and five minutes later I was outside David’s house. Minutes later Wilko the Sat Nav Supremo pulled up in second place. I couldn’t find my mobile for the 7.30am departure either, so it was victory for traditional methods. Which rather suits a tale about a 1960 bike.

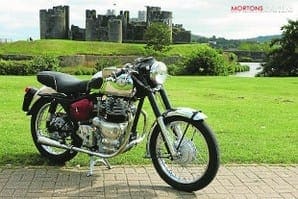

It looked pretty sleek and purposeful, very different from the Constellation I remembered. On closer examination it was only slightly altered, though the latest rebuild had given it a cosmetic lift with little details looking much smarter. The standard Connie handlebars had been refitted upside down and its footrests were moved back to the pillion mounting points to complete the Clubman’s look. The rear sets showed Rose joints on the linkages, which suggested a proper standard of components used. If you’d seen the bodge I made converting an ohc OK Supreme 250 to sprint trim in my youth, you’d be happy to applaud a decent job.

It wears a modified dual seat because David wanted it for strictly solo use and a racing style seat was too uncomfortable. The reversed handlebars don’t give an extreme riding position, just the facility to adopt a sporting crouch; anyway, a bike with a headlamp just doesn’t look half good if you try to go for the whole café racer style. That nacelle deserves close inspection, a fine one-piece example of the foundry-man’s skill in alloy, and better quality than the steel pressings from Triumph. I know Triumph did it first and they certainly built handsome motorcycles, but what Enfield did was more of a quality item.

It wears a modified dual seat because David wanted it for strictly solo use and a racing style seat was too uncomfortable. The reversed handlebars don’t give an extreme riding position, just the facility to adopt a sporting crouch; anyway, a bike with a headlamp just doesn’t look half good if you try to go for the whole café racer style. That nacelle deserves close inspection, a fine one-piece example of the foundry-man’s skill in alloy, and better quality than the steel pressings from Triumph. I know Triumph did it first and they certainly built handsome motorcycles, but what Enfield did was more of a quality item.

David found the bike when he was working in Canada and got chatting to another Royal Enfield enthusiast. The man knew of a yard full of Enfields, across the border in Ohio, and reckoned there was a Connie for sale; you can guess where the next weekend found them.

“The yard had about 30 Royal Enfields, standing in the open,” David remembers. “I bought this one, and the chap found the side panels and other bits that had been stripped off it.” It was a sorry looking wreck, and out of respect for CBG readers’ sensitivity, I declined the loan of a picture of the bike as bought; it would make strong men weep. However, with all the bits gathered, it was a complete 700cc Constellation, ripe for restoration by somebody brave enough. David Williams is, and he brought the bike back to full health.

On returning to Wales, David followed up the bike’s history through the REOC, who have some of the factory records. Amazingly, this bike was despatched in 1960 to a dealer in Caerphilly, not a day’s march from where it lives now. How it got to Ohio is unclear, but it’s been to the USA, had a tough 30 or so years there, only to be rescued, restored and brought back to its spiritual home.

On returning to Wales, David followed up the bike’s history through the REOC, who have some of the factory records. Amazingly, this bike was despatched in 1960 to a dealer in Caerphilly, not a day’s march from where it lives now. How it got to Ohio is unclear, but it’s been to the USA, had a tough 30 or so years there, only to be rescued, restored and brought back to its spiritual home.

When I checked with Roger Boss, whose rise from production tester to sales manager we covered in CBG many moons ago, he remembered Morgan’s of Caerphilly in his time as the company rep covering that area. “The first time I called they had a bike giving them trouble. Don’t remember which model it was, but I re-timed it and cured the problem. They were impressed that a rep could actually get his hands dirty and sort a bike out,” he recalled.

So what about that Ontario registration plate I’d seen all those years ago? “It was just a plate I had left over from a previous registration,” David explained. “I put it on for that Ponthir Club run because I hadn’t got the registration details sorted out here, and I thought that any copper who stopped me and saw that would think about all the paperwork and not bother.” Today, it’s strictly legal. Well… maybe that megaphone silencer wouldn’t stand close examination with a noise meter, but when kicked into life, it did make a deep noise. Pavarotti on wheels.

“The front brake needs watching, it’s a bit snatchy at low speeds, but fine once you’re getting a move on, and the gearbox is the bike’s weak point,” David warned. I could understand that, and a frustrating ride on a beautiful 750cc Interceptor spoiled by the erratic availability of Albion’s four ratios came to mind, but I could also remember a fantastic Interceptor Metisse which apparently had its sluggish gearbox cured by a replacement spring in the selector mechanism. The outstanding memory of them both was the flexibility and power of that motor.

The air lever was used once in our day, when David started it from cold. The control most unusual to younger eyes will be the ignition advance and retard: “Back it off a bit to start it, then put it on full advance for riding,” was David’s advice. In these days of engine management systems, such a manual control is an anachronism, but it dates the Constellation back to the days when men were men and expected to exercise full control over all functions…

The air lever was used once in our day, when David started it from cold. The control most unusual to younger eyes will be the ignition advance and retard: “Back it off a bit to start it, then put it on full advance for riding,” was David’s advice. In these days of engine management systems, such a manual control is an anachronism, but it dates the Constellation back to the days when men were men and expected to exercise full control over all functions…

Easy to control, this big Enfield proved to be at first acquaintance, pulling easily along at little more than tickover in Cardiff’s crowded suburbs, with the Albion box swapping gears easily and reliably at low speeds. With a little throttle tweak the promise of a deep throated roar began to emerge and turn the heads of those who knew something about bikes. David was quite right about the twin six-inch single leading shoe drum brakes at the front, which had the forks dipping if applied quickly in traffic, but out on the open road, the bike stopped impressively with no discomfort. The obvious solution with such a stopping system is to keep town riding to a minimum and get out and about in the country at a decent rate of travel; the Institute of Advanced Motorcyclists call it 'making progress'.

The comfort of the riding position was a pleasant surprise, even if the footrests are further back than most riders would choose; when we chatted about them, David did admit he’s considering small plates to move them forward a tad. Maybe a tad and a half. The simple matter of unbolting the handlebars, turning them upside down and mounting all the same gubbins back in place would have made a lot of sense in the days when the bike could be used to ride to a speed event, like a sprint or a club road race, to compete and then ride home – assuming you hadn’t had too much red mist obscuring your judgement and not thrown the bike down the road with consequent damage to transport home or self. I can remember PA appeals at Brands Hatch, asking if anyone had room for a bike and rider back to somewhere beyond the reach of public transport system.

The comfort of the riding position was a pleasant surprise, even if the footrests are further back than most riders would choose; when we chatted about them, David did admit he’s considering small plates to move them forward a tad. Maybe a tad and a half. The simple matter of unbolting the handlebars, turning them upside down and mounting all the same gubbins back in place would have made a lot of sense in the days when the bike could be used to ride to a speed event, like a sprint or a club road race, to compete and then ride home – assuming you hadn’t had too much red mist obscuring your judgement and not thrown the bike down the road with consequent damage to transport home or self. I can remember PA appeals at Brands Hatch, asking if anyone had room for a bike and rider back to somewhere beyond the reach of public transport system.

Only when we stopped did I realise that my arms ached slightly, with my upper body weight resting on them during city riding. David pointed out that to combat the effects of storage in the garden shed, he’d sprayed cylinder heads, hubs, carburettor bodies, gearbox shell and crankcases with either high temperature or petrol resistant paint. Did a reet good job, too. The matter of crankcase breathing has been addressed with a 10mm tube tapped into each rear tappet inspection cover, exiting in the general direction of the rear of the bike.

Right, let’s get out of suburbia and explore the bike’s open road performance, which means riding at legal(ish) speeds and trying not to get the innocent owner one of those greetings cards from the constabulary, with a bill for £60 and a sprinkle of points on his licence. A brief spell on the A470 was no joy at all, with two crowded lanes and little chance to give the bike its head; just once I gave it a fair bit of stick and the speedo needle whizzed past the 70mph mark with the bike accelerating strongly in top.

The nicest bit of the open road experience was the smoothness of the engine; much sweeter than Triumph’s T140, Norton’s Atlas or BSA’s Rocket Gold Star at that sort of pace. Handling is hardly tested on smooth modern highways, but as we explored some of the lesser highways the bumps began to emerge and the front end danced mildly over the ups and downs of the surface. The rear end still depends on the original Armstrong dampers, dismantled, checked and rebuilt, and they rode the rougher tarmac very well. There was one section where I was thraping the bike backwards and forwards for the camera’s benefit and to turn around meant riding down a narrow, winding hill with a worn surface on one side. I deliberately chose that bumpy section as 700ccs of Enfield’s finest pulled strongly towards the legal limit and it gave just the slightest twitch or two, but nothing to worry even this unfamiliar rider. I was impressed.

The nicest bit of the open road experience was the smoothness of the engine; much sweeter than Triumph’s T140, Norton’s Atlas or BSA’s Rocket Gold Star at that sort of pace. Handling is hardly tested on smooth modern highways, but as we explored some of the lesser highways the bumps began to emerge and the front end danced mildly over the ups and downs of the surface. The rear end still depends on the original Armstrong dampers, dismantled, checked and rebuilt, and they rode the rougher tarmac very well. There was one section where I was thraping the bike backwards and forwards for the camera’s benefit and to turn around meant riding down a narrow, winding hill with a worn surface on one side. I deliberately chose that bumpy section as 700ccs of Enfield’s finest pulled strongly towards the legal limit and it gave just the slightest twitch or two, but nothing to worry even this unfamiliar rider. I was impressed.

The Albion gearbox had been fine when demands upon its operating system had been at a low level but when exercising the bike a little more enthusiastically, winding it up and treading the gears through fairly quickly, twice the change from second to third found the gearbox in a neutral between third and top, and progress was delayed while I cautiously pressed down for top and then dropped a cog into third and set about building the forward impetus again. If you were out to 'make progress' with your mates on Nortons, BSAs, Triumphs or AMC-ware, it would be embarrassing. In racing, particularly a Thruxton marathon, it could be a disaster, but on the road you adapt, don’t ask too much of the change mechanism, and the world seems a harmonious place again.

There wasn’t a drop of oil under the bike whenever we parked, nor at the end of the day. Forget that nonsense about Oily Enfields, they just need to be put together carefully.

Why a 700?

Why a 700?

In the early 1950s, Triumph and BSA were enjoying strong sales with their 650cc 6T Thunderbird and A10 Golden Flash. In 1953 Royal Enfield offered the 700cc Meteor, an amalgam of 350cc Bullet dimensions at 70mm bore x 90mm stroke and the 500 Twin’s crankcase castings. Instant big bike and in 1952 the prototype was running around the Midlands disguised as a 500 and putting the wind up testers like the Ariel men out on Selly Oak’s genuine half litre. When one man struggled to stay with what he thought was a 500 Enfield with sidecar attached, they must have been worried about what was brewing down the road in Redditch.

The Super Meteor carried factory ace Jack Stocker to a Gold Medal in the 1953 International Six Days, just to prove how adaptable the big bike was. In 1957 the factory was working on an uprated version, the Constellation, launched for the 1958 season with its nodular iron crankshaft dynamically balanced. Big ends were shell bearings and the clutch was beefed up to cope with a claimed output of 51bhp at 6250rpm. Please note, bhp means British Horse Power, those big shire ones with the muscle to pull a castle over, and not to be confused with claims from lesser sources. I shouldn’t quote the poor innocent who wrote to a weekly claiming that his 250cc Ducati could do 120mph, because he’d seen it on his speedo. The Constellation was quick without silly claims. ![]()