Still Running, Still Riding: The traditional half-litre single is still on sale! Yamaha’s SR road banger has been in production since 1978. That is a very long time indeed, so it must be something special…

Words by Steve Cooper Photos by Stu Ross, Andy Leicester, Marcus Rex

When Shiro Nakamura and his team sat down sometime in the early 1970s to design a new engine it would have been safe to assume they had no idea that their creation would still be alive and well more than four decades on.

In the main, Japanese motorcycles have relatively short production runs; if a model remains true to its original design brief for more than 10 years it’s the exception rather than the rule.

Yet here we are in 2016 and against the odds Yamaha is still selling essentially the same machine – with just a few nods towards emissions requirements and licence restrictions.

And this is no mean achievement when you grasp that what we’re talking about here is an air-cooled, two valve, four-stroke single.

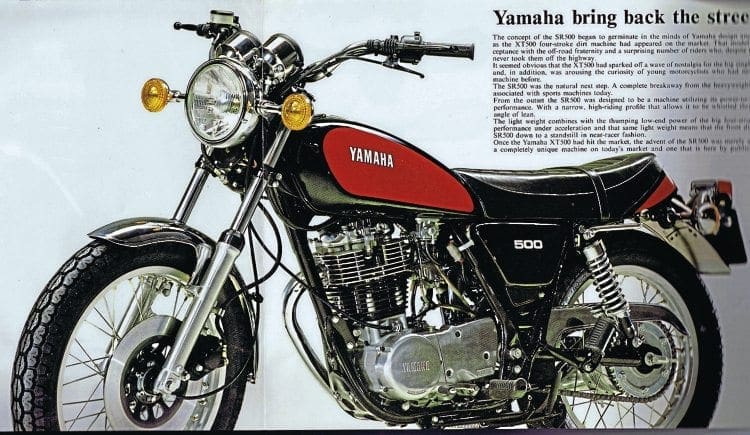

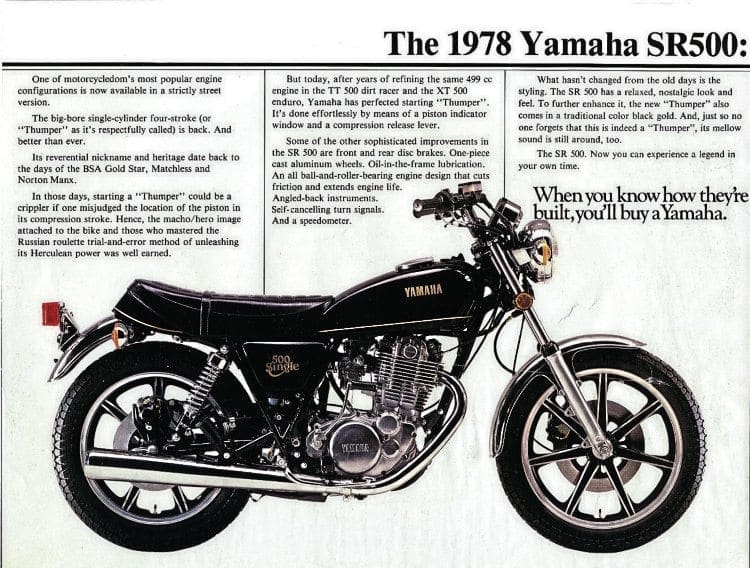

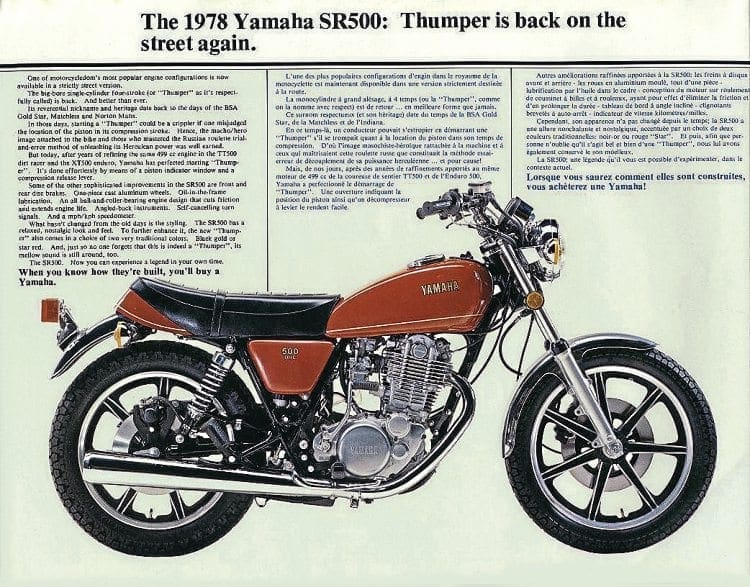

Our subject matter, the Yamaha SR500, began life in 1978, but its origins are a little older and are inextricably linked to the XT500 trail bike.

The two engines share a related if sometimes disparate development history and inevitably the time-honoured chicken and egg scenario cannot be escaped.

The XT motor was developed in response to US dealers demanding a bigger, faster and more environmentally compliant dirt bike.

Having previously distanced themselves from off-road twins, Yamaha was inexorably drawn to the four-stroke single, mostly due to its slim profile.

Countless British half-litre singles had been the weapon of choice for decades in road, race track and dirt applications.

Even when pushed beyond their design capabilities the concept still stood up in competition scenarios, where engines could be frequently rebuilt and cost wasn’t an issue.

Viewed dispassionately, the Japanese mind set asked two questions: Was the 500cc single still a viable concept? If so, could it be made in such a manner that its perceived issues might be overcome? History shows the answer to both was yes.

In 1975 the XT500C was launched to generally rapturous applause and would run with only minor revisions and updates until 1990.

We come into the story three years on from the launch, when Yamaha factory bosses bit the bullet and produced a purely road orientated version in the guise of the SR500.

The dirt-focused XT had been inspired by legions of 500cc, go anywhere, do everything, single lungers and the new off-roader had inescapably provided a road bike. Fowls and their embryos, etc.

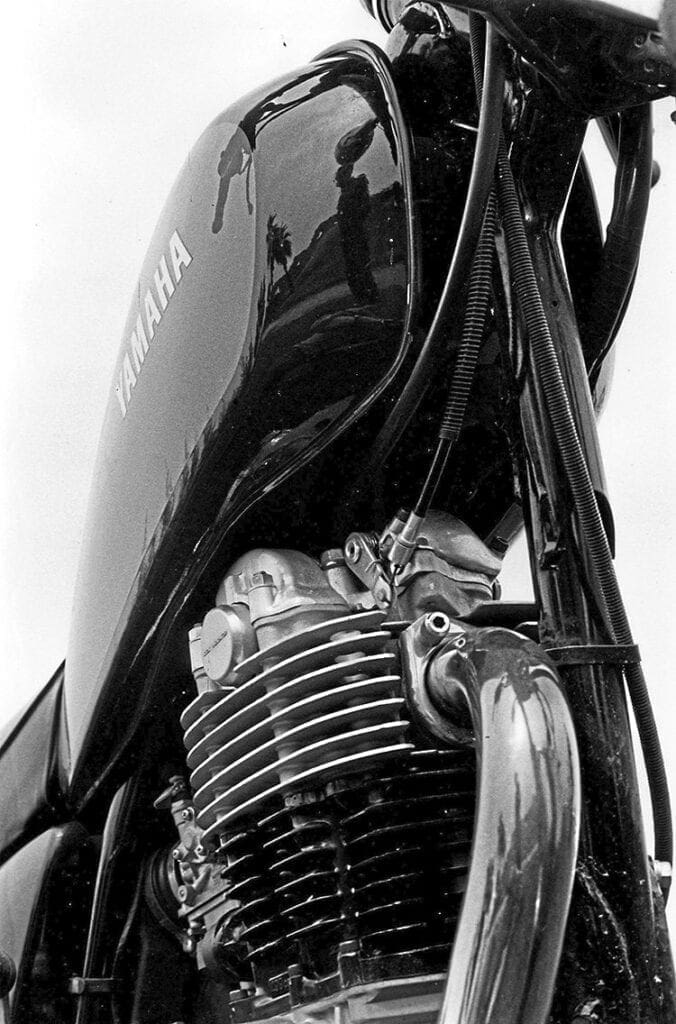

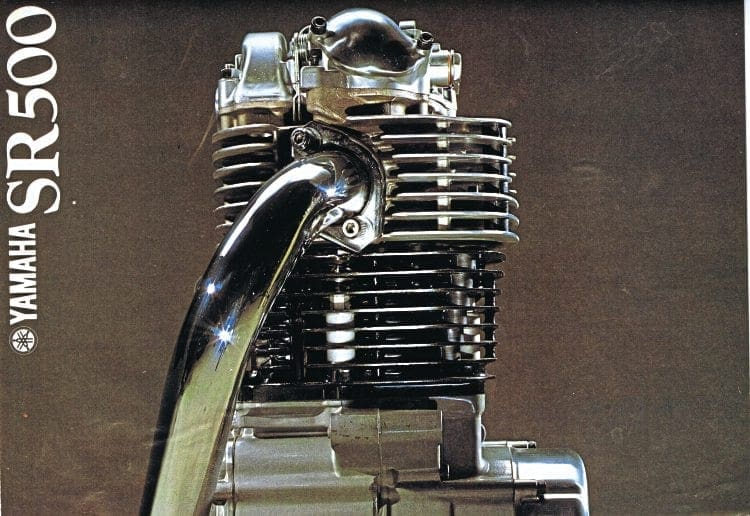

The XT and the SR share a similar basic architecture in that they both run dry sump motors supplied with essential lubrication from an oil containing frame – but beyond this there are marked differences.

Without wishing to sound disparaging, Yamaha’s engineers knew they couldn’t save money by making the same sorts of compromises BSA’s lads were forced to accept in the last tumultuous years of the empire’s death throes.

Crankshafts on the XT and SR are fundamentally different, with the road bike running larger webs.

The pistons also reflect dissimilar end-use applications, with the SR running a longer skirt.

And the inlet side of things is much more road bike focused.

The cylinder heads are different, with the road bike utilising inlet valves 2mm larger than the XT’s at 34mm, aimed at flowing more gas at higher road speeds.

The trail bike was criticised for poor starting (hot or cold) which is as much a facet of big singles as it is of Yamaha’s engines, but the Iwata team offered a potential solution.

The combination of a CDI ignition system allied to 12 Volt electrics went some way to addressing the issues even if it didn’t totally allay car park histrionics.

Additionally, decompressors, TDC indicators and a strict proscribed regime from the owner’s manual only ameliorated the situation.

Even the SR’s successor, the SRX600, was similarly afflicted and it wasn’t until the introduction of an electric foot on the SRX600E that Yamaha finally had a big four-stroke single that could be predictably and reliably fired up time after time.

Thus is the nature of the beast … as they say.

Within the UK the SR500 was and has been marginalised as being something and somehow less than the feisty old British machines it’s perceived as aping.

Yet rose-tinted spectacles also have a nasty habit of twisting perspectives. Yamaha never set out to make a machine that was the equal of a Velocette Thruxton or a BSA Gold Star.

Both of these machines were the zenith of their genre, but at the same time they were also potentially divas prone to hissy fits and angst-ridden pique.

With just 33bhp on tap at 6300rpm the SR was more of an everyday machine designed, engineered and built to deliver the joys of half-litre single ownership without the pain traditionally associated with the experience.

At its launch and subsequently, the SR500 was often damned with faint praise for not being some sort of snorting latter-day rocker’s missile.

However, and this will undoubtedly offend some readers, neither did it suffer the reliability issues associated with the BSA B50, which offered similar performance.

Much development work had gone into the XT and SR engines and the use of forged, one-piece connecting rods, allied to needle roller big ends and low pressure oil pumps, delivered a narrow motor famed for both its reliability and its oil-tightness.

These were the attributes the public had come to expect and this what the factory had to deliver. Obviously, Yamaha was unable to rewrite the laws of physics and therefore the SR500 did vibrate.

It wouldn’t be until the fitment of multiple balance shafts and dummy non-functioning pistons that singles could offer anything less than what’s politely referred to as ‘typical character’.

If the SR500 failed to inspire here in Britain, elsewhere the delights of a modern half-litre single were much better received.

Mainland Europe in general and Germany in particular took the bike to their hearts.

Before the SR500 was dropped from the sales list in 2005 (due to increasingly tight emissions requirements), almost 40,000 of Yamaha’s big road-going singles were sold in Germany alone.

Yamaha had also been quick to release a 400 version for the home market, complying with national licence requirements.

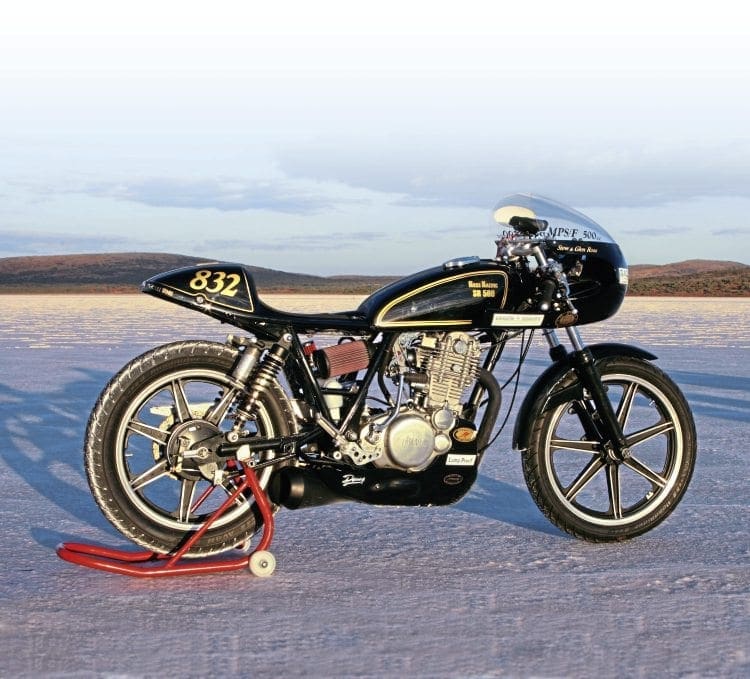

Both bikes have been staunch favourites down under in Australia, and to this day they enjoy huge success as both a road bike and a competition machine.

And of course it was probably preordained that the bike would find huge success back in its own country, where the cult of the SR fostered innumerable specialist parts manufacturers.

At various times it’s been possible to equip an SR with everything from the inevitable alloy tank, clip-ons and rearsets through to high lift cams, big bore and stroke kits, ball-footed tappet adjusters and even external flywheels that would bestow Brit Iron characteristics.

Throw in eye-wateringly expensive eight leading shoe front brakes cast in magnesium and it’s fair to state that Yamaha’s half-litre single has been as well catered for as any 50s’ British equivalent.

Motorcycle manufacturers often have the unerring gift of messing about with perfectly good designs and making them worse.

Amazingly, and against the odds, Yamaha have had the good sense not to do this.

Other than considered revisions and upgrades, the SR400 on offer today looks remarkably like the SR500 of 1978.

Various market trends have dictated fitments such as cast alloy wheels instead of wire spokes, drum brakes in place of discs, colour schemes and graphics, but by and large the SR’s profile remains true to its roots.

In its original form, the bike ran a 19” front and 18” rear wheel, 34mm Mikuni carburettor, disc front brake and drum rear. From 1985-on, the bike ran a competent twin leading front brake in a bid to attract purists who felt the look better suited a 500 single.

A few post ’85 bikes still retained the disc, but these are likely to have been run-out models using the last of the old stocks.

In a bid to improve handling and tyre choice, the front wheel dropped to 18”, but quite why Yamaha saw fit to reduce tank capacity from 14 to 12 litres was never really obvious.

Three years on, the bike got a revised camshaft profile that enhanced low- and medium-speed running and an updated carburettor to assist with both fuelling and starting.

Although rarely if ever sold in the UK, this was one of the models that sold at consistent levels around the world and convinced the factory that there was still substantial mileage in the concept.

In fact this, the 1988 model, remained substantially untouched until 1993 when the ignition system was revised.

Increasing national legislation demanding the use of daytime riding lights was putting unreasonable strain on the electrics; yet again Yamaha was showing commitment to the cause by upping output to match demand.

1999 saw the final SR500s role off the production line, but the 400 was still considered a very viable piece of kit and continued to be made in serious numbers, if primarily but not exclusively, for the Japanese domestic market.

2001 was to see the AC CDI ignition swapped out for a DC system which was said to aid starting and ignition timing.

With ever-tightening emissions legislation the carburettor gained a throttle position sensor, but this was only an interim fix.

From 2010 the SR400 was fitted with fuel injection to become one of a small group of air-cooled motorcycles still able to meet global noise and pollution legislation, which is a pretty cool achievement for a bike launched in 1978 with an engine conceived circa 1972/3.

The big SRs have always provoked a loyal following, but not necessarily from the purists.

It’s really not the sort of bike you’d expect to find at a Stafford concours show.

Many machines sport upgrades and modifications bestowed upon them by owners in order to enhance the experience and/or remove some of the neutering Yamaha was obliged to install.

Top item on the list is normally a free-flowing exhaust to replace the standard factory item, which utilises a rather contorted, capacious and corrosion-prone middle section just behind the gearbox.

The next considered modification is a freer-flowing air filter facilitating better flow dynamics. These two revisions alone can transform the way the engine makes its power.

From here on the sky is almost literally the limit, and well before Yamaha rediscovered or rebranded the concept of individualism owners were personalising their own machines.

The most popular and obvious conversion is by default the café racer, but flat trackers, bobbers and even choppers have been wrought from Iwata’s engineering.

Riding an SR500 is like little else. It’s emphatically one of that handful of first generation Japanese four-stroke big singles, but it’s never, by any stretch of the imagination, compromised.

Any notion that it’s in some way a roadsterised XT are swiftly banished.

Once started (the word ‘technique’ is entirely appropriate) the first impression is one of size, or rather the lack of it.

Yamaha resisted the temptation to play around with the natural attributes bestowed by a large single-pot motor and therefore the bike looks and feels slim.

Looking down, there’s nothing significant protruding beyond the tank.

The seat’s a decent size, the footrests aren’t stupidly too far forward and even the models with higher bars don’t dictate a windsock riding position.

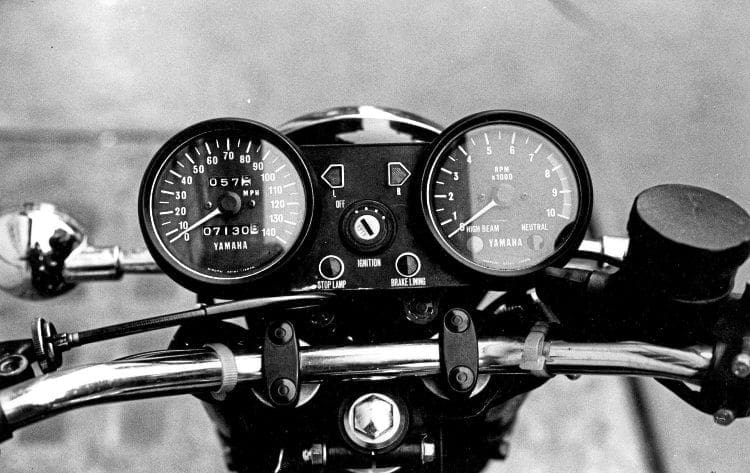

Clocks are purely period Yamaha, ditto controls and lights; it all works logically and is elegantly simple. If ultimate speed is your goal, look elsewhere cos that’s not what the SR is about.

But if you value prize agility and stability this is the machine for you.

Period road tests were surprisingly complimentary about the bike’s handling, as if suggesting this was some superhuman technical achievement, yet Yamaha had been delivering pretty much class leading handling in machines such as their YDS7, YR5, and RD250/350 for years.

It was only the earliest 650 twins that gained a reputation for slightly wayward wobbling.

With a quoted 33bhp on tap the engine was never likely to overpower the chassis and even the OEM suspension was better than just OK back in the day.

Four decades on some decent period-looking shocks, progressive fork springs and, crucially, modern rubber will have the SR flying around radii of all kinds.

In terms of braking, the original models ran a single front disc and sliding, single-piston calliper that was more than up to the job of retarding a light bike. The rear drums are effective and predictable.

The later models were equipped with a twin leading shoe front end, which does what it says on the tin; historically, Yamaha’s TLS units have always punched above their weight.

If you ride it as it demands and don’t think ‘Panther single’ then you’ll be rewarded with a great experience.

However, if you’re expecting huge gobbets of torque at low revs in top gear you’ll be cruelly disappointed; simply put, it isn’t that sort of half-litre single.

Although speed was never the bike’s raison d’être, it does make the best of what’s on offer.

Variously documented as being capable of 86-96mph it’s not the fastest of its ilk, but crucially it can run pretty much any speed that’s dialled into it and can sustain said velocity – gradients and headwinds excepted.

Like any big single an SR500 can, does and will vibrate, but it’s emphatically a Japanese machine and its creators made strenuous efforts to ensure the worst excesses of an 87mm piston traversing an 84mm bore don’t impact unduly on the rider.

Comprehensive rubber mounting of key items means nothing gets too badly buzzed, but the quintessential half-litre single is always there.

The worst of the vibes occur circa 5500rpm, which is perversely where maximum torque is produced.

The standard response is to either ride through it or around it, but even at its worst the bike is never as raw and visceral as Gold Star.

And that may well be the SR500’s Achilles heel. It isn’t a Goldie or a rorty Velo, and if it actually mimicked either it’d be similarly blessed or cursed with their attributes (depending on your point of view).

Yamaha set out to design a 500cc single from first principles, but if you believe they sanitised it then you are missing the point. Both the marketing guys and the boffins at Iwata conceived the rebirth of the first internal combustion engine, period.

The idea that Yamaha were the pioneers of the modern four-stroke single is regularly overlooked, but it was there people who breathed new life into a concept many thought was past its sell by date.

Know that the SR400 is still a current model, alongside stunning singles such as the XTZ660Z adventure bike and the awesome WR450F moto-crosser, and give thanks that someone had the cojones to single-handedly deliver the goods!

Faults and foibles

Generally the SR is a tough old bird and many long-term owners refer to them as being pretty much bulletproof.

The SR’s engine is essentially a reworked XT mill and as such was only Yamaha’s fourth four-stroke. After the disasters that were the TX500 and TX750 they went back to what they knew best. The seminal XS650 had majored on ball and roller bearings and thus was a safe bet to emulate.

A pressed-up crank à la two-strokes makes for a solid bottom end; ditto a cam that runs on ball races rather than direct in the alloy head. Poorly adjusted tappets make a fair impersonation of a death rattle, but are easily rectified.

Worn camchains and/or adjusters make similar distress calls, but take a little more input to sort. Bore, piston or ring wear can be an issue, especially if the bike has been run with a primitive air filter (or none at all).

Normally the rings and pistons will be good for 35-40k miles, if not more. Some SRs have been known to take out cam lobes and/or followers.

Top-end oil-feed kits have been a favourite upgrade over the years, and investment in such undoubtedly delivers more lubrication to the hottest spots of the motor.

The other key improvement that’s possible in this area is to use decent oil from day one or immediately after a rebuild, and then change it and the filter regularly.

The OEM carburettor is said to be something of a compromise between emissions and fuelling a big single.

The low-cost, easy use, simple-fit solution is a replacement Mikuni 34 or 36mm aftermarket carb. Once set up they tend to be reliable in use and consistent in performance.

Most of what’s needed to keep an SR running is available as pattern parts and with Yamaha being prolific in its parts standardisation there’s a better than evens chance that outside of the motor something else will fit.

The Perr group and beyond

The reality is that the SR500 didn’t have any contemporary peers, but it was the catalyst for more than a handful of wannabees.

Honda missed a trick initially and then came back with the XL500 based Ascot or FT500.

Under either guise their take on the SR bombed. It was doubly cursed by not having a kickstarter and being equipped with an electric foot that was flawed in both design and operation.

Yamaha upped the ante on themselves with the SRX600, which was supposed to be an improvement but arguably was an answer to a question few had posed.

At the same time Honda came back in loud and proud with the XBR (later GB) 500 featuring a radial four-valve head.

Built to a higher standard than the Yamaha eRX, the bike was well received but never sold in the same volume as the SR, arguably proving Yamaha had got it right first time.

Within a few years everyone from Kawasaki and Suzuki to Gilera was offering a big four-stroke single in road and/or trail format, suggesting that imitation really is the sincerest form of flattery.

Even the Les Harris Devon factory, normally busy making, Triumphs had blagged some Rotax motors and the Matchless badge in a bid to cash in.

Perhaps the most ironic twist of the SR saga came when the BSA Regal group tooled to produce the BSA Regal SR500 Gold Star.

Using a Yamaha-supplied engine and a British-made frame, the resultant bike was either the worst of comprises, the best Goldie ever or a cynical ploy to trade on an ageing reputation.

Or was it the best single cylinder motorcycle BSA never produced?

Yamaha SR400: another modern classic

Due to home market legislation, Yamaha also produced a 400cc version almost from the off alongside the 500, so it’s politic to include it in any review of the bigger SR.

Given the buoyant state of the classic market, more than a few have found their way here. Essentially using pretty much the same running gear as the 500, the smaller engine was achieved by lopping 17mm from the stroke plus a few internal mods.

Other than a break in production in 2007/2008, Yamaha has fielded an SR400 or 500 since 1978.

With modern motorcycle sales now looking towards an increasingly older demographic, the SR is back on sale in the UK in the guise of the SR400, now fitted with fuel injection to make it Euro whatever compliant.

It may cost north of £5000 and deliver something a little shy of 25bhp, but it offers the tautological concept of modern nostalgia to a clientele that’s not totally won over by Indian-made Royal Enfields.

The cost might make die-hard classic owners wince, but when you factor in just how much it’s likely to cost to restore an original SR500 the numbers actually stack up rather nicely.

With the current craze for bobbers and customising, Yamaha has been canny enough to offer a few SR400s to leading builders just to show what’s possible with a 40-year-old design.

Even if nostalgia’s not what it used to be, Yamaha hasn’t lost sight of the past.

Both its website and the owner’s handbook make capital of the starting technique redolent of back in the day.

Quote … “First you pull the decompression lever (below the clutch lever) and slowly rotate the kickstarter to get the piston in the correct starting position.

That position is indicated in the looking-glass in the cylinder. When the indicator is in front of this glass, it is in the correct position. Then you let go of the decompression lever and let the kickstarter go up fully. Take a deep breath. The bike is ready to start!

Now give a strong kick. No hesitations here: give it all you got, let the kickstarter go down all the way with a lot of speed…. and beware that you don’t touch the throttle at all before the bike starts and runs!

If the bike did not start, or even if you gave only a small push to the kickstarter, then ALWAYS go back to the start of the ritual: get the piston in the correct starting position and only then try to kick it.

Never try to kick it when the piston is off the correct position. If you do this well, the bike will start at the first kick, surprisingly easy! It’s like a magic trick: On-lookers imagine that it needs a lot of force to start it, but when you know the trick it is so easy”

Read more News and Features online at www.classicbikeguide.com and in the May 2020 issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!