For many Moto Guzzi enthusiasts, a pilgrimage to Mandello del Lario fulfils a lifetime ambition. Frank Melling presents a whistlestop tour

WORDS BY Frank Melling PHOTOS BY Carol Melling

IN AN ATTEMPT to be objective, I should say that the Moto Guzzi museum – at Mandello del Lario, on the banks of Lake Como in northern Italy – has relatively few motorcycles on display for a world-class museum.

It’s housed in an old building, dating from the 1920s, and the displays are plain and utilitarian.

Also, in purely objective terms, visitor facilities are poor.

Admission is free of charge.

There are no audio guides or booklets to lend a helping hand.

This is a museum fit only for the dedicated Moto Guzzi acolyte. Voyeurs, bystanders and tourists need to seek their historical thrills elsewhere.

However, I find it nigh-on impossible to be objective about the Moto Guzzi museum.

Despite all its faults – or maybe even because of its foibles – this is a shrine not only to motorcycling but to human endeavour.

Nowhere in the world will you see human creativity more clearly and overtly manifested than in this rather dowdy display of motorcycles and motorcycle engineering.

You know that something special is about to happen when you enter Mandello del Lario.

Squeezed tight up against the mountains on one side and the water on the other, the town proudly proclaims that it is ‘Citta dei Motori’.

Drive further along the narrow road and there on the left is a small, somewhat grubby, car park.

It bears the plaque ‘Piazza Carlo Guzzi’, for Mandello del Lario is Moto Guzzi and Moto Guzzi is Mandello del Lario, with each enjoying their mutually symbiotic relationship.

The Moto Guzzi factory was built in 1921 – and looks as if it was.

The Piaggio Group, which now own the Moto Guzzi brand, is starting to rebuild the site as Guzzi production ramps up, but the iron-framed windows, carrying more than 90 years of paint, bear testimony that this is an authentically historic building.

The entry to the museum is anti-climactic in the extreme.

There is no huge artwork proclaiming what the visitor is about to see; no theme park welcome by gleaming-toothed hostesses and no offers to dine in an ‘authentic’ 1930s Italian restaurant.

Instead, one ascends a set of worn stairs and, quite suddenly, you are thrust into the presence of greatness…

THE MOTO GUZZI museum is open most weekday afternoons with extended hours during July, but is closed some public holidays so check in advance. Join Mr Melling for a guided tour at youtube.com/watch?v=6nsfR9TFvb4

GP & NORMALE

CARLO GUZZI’S FIRST motorcycle from 1919 represents the fanfare of trumpets which launches the show.

It wasn’t a modified bicycle with a proprietary engine bought in from Switzerland or England.

Guzzi said that there was a better way of making a motorcycle than just adding an engine to a bicycle.

The better way was a forward-facing, single-cylinder engine which could be air-cooled because it was in the correct place to catch the airflow.

The engine had an overhead cam and four valves so that it breathed well.

There was an outside flywheel, which came to be called the ‘Bacon Slicer’, so that the crankshaft was stiff and the motor had low vibration.

The primary drive was by gear, rather than chain, with a three-speed, unit- construction gearbox, and automatic lubrication at a time when riders were expected to pump oil to the engine manually. Guzzi did not so much improve motorcycle design as rip it to shreds and start from new.

These same ideas were to dominate Guzzi’s thinking for the next 50 years.

Carlo Guzzi was only able to develop his superior hand axes because his partner was Giorgio Parodi.

Guzzi and Parodi had been colleagues in the Italian Servizio Aeronautica during the First World War and the Parodi family fortune, made from shipping and armaments, bankrolled the whole project.

Guzzi was an aircraft mechanic and Parodi a pilot. Their close friend Giovanni Ravelli was killed in 1919, so Guzzi and Parodi determined to keep his memory alive by using the legendary soaring eagle on every motorcycle they made.

In fact, the first ‘Guzzi’ is actually called a GP – to recognise the Guzzi/Parodi link – but the young Giorgio’s family were so concerned about the adverse publicity if things went wrong with the new venture that they had the Parodi element of the name dropped, and so Moto Guzzi was born.

Mr Parodi Snr deemed the GP too complex and expensive to make to be profitable, and so in 1921 the much simpler Moto Guzzi Normale went on sale.

The Normale Norge which followed was one of Italy’s first motorcycles to reach the Arctic circle.

THREE CYLINDER ‘TRE’

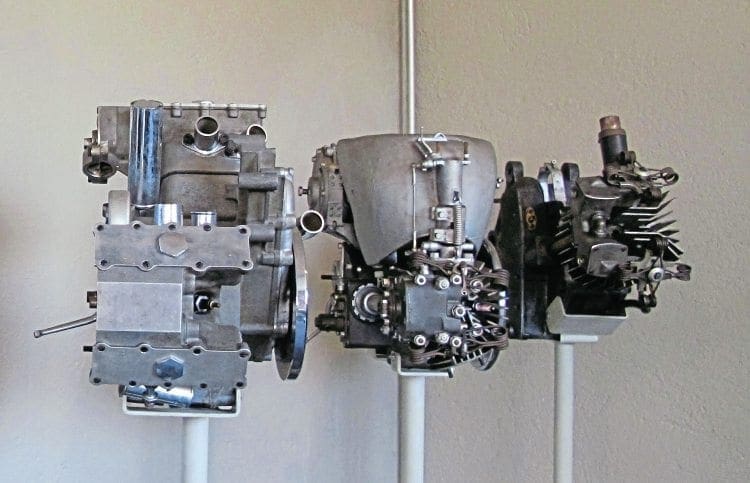

GUZZI WASN’T ADDICTED to single-cylinder racing. Towards the end of the gallery, there is a magnificent display of supercharged singles and V-twins, and the utterly sublime, three-cylinder Tre.

In an act of incredible generosity, my hosts allowed me to cross the barrier and touch the Tre, and to do so was a quasi-religious experience.

The three inclined water-cooled cylinders would be state of the art for 2015 – as would be the neat supercharger tucked away above the engine.

The 500cc engine produced 65bhp at only 8000rpm, so it is reasonable to think of 120bhp plus for a 1000cc engine – or about what a current sports touring machine is making.

The difference is that the Guzzi dates from 1940!

Along with a science-fiction-sophisticated engine, the Tre featured a spine frame containing the engine’s oil. Neat, compact, and barely any wider than a 500cc single, the Tre was destined for stardom … except for the FIM’s ban on superchargers. I simply stood in awe next to

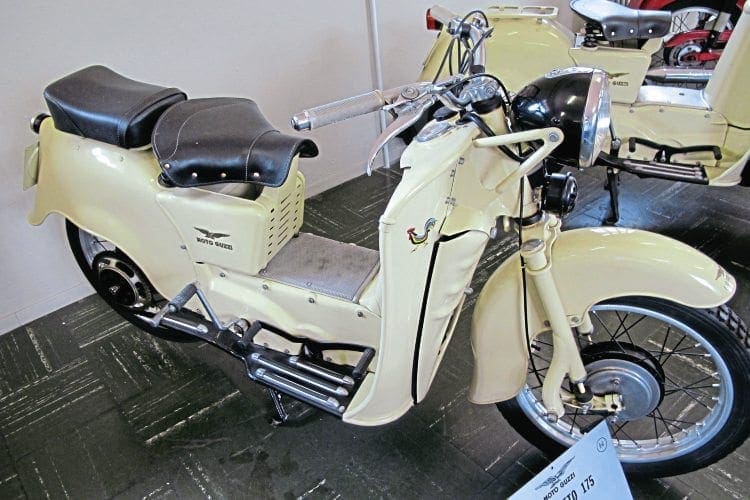

GALLETTO

GUZZI’S INTERPRETATION OF a truly practical scooter was first produced in 1950, in direct response to a post-war Italy starved of personal transport.

The Galletto 160, carrying the nickname ‘The Priest’s Scooter’, was a 160cc, 6hp machine, which enabled the local priests (there were an awful lot of the clergy in Italy) to get around their parishes quickly, economically and safely, even on poorly made roads.

With an alloy cylinder and barrel and, naturally, a horizontal engine, the Galletto was safe, easy to ride and a real workhorse – and it made Guzzi a huge amount of money.

V7 ROADBIKES

THE MUSEUM INCLUDES a huge display of Guzzis derived from the V7 military, ATV engine; they are fascinating. Dr John Wittner’s Daytona race bikes are magnificent, as is the regal Moto Guzzi California Police bike.

Don’t overlook these in your haste to see the exotic racing machinery

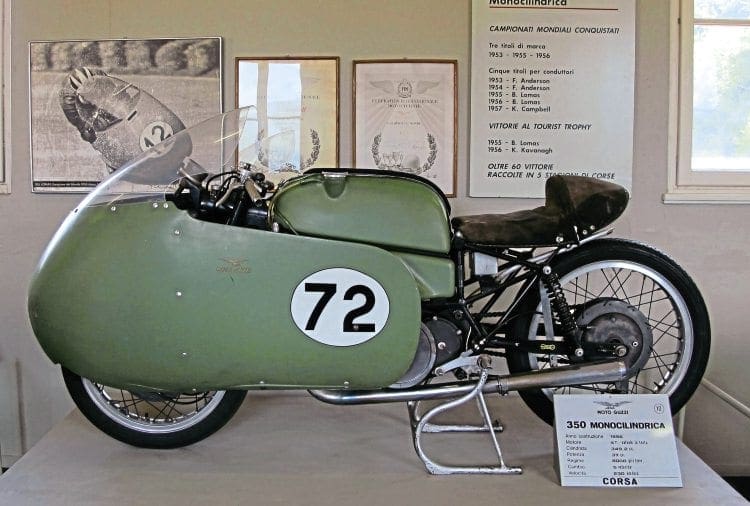

1955 WORLD-BEATING 350

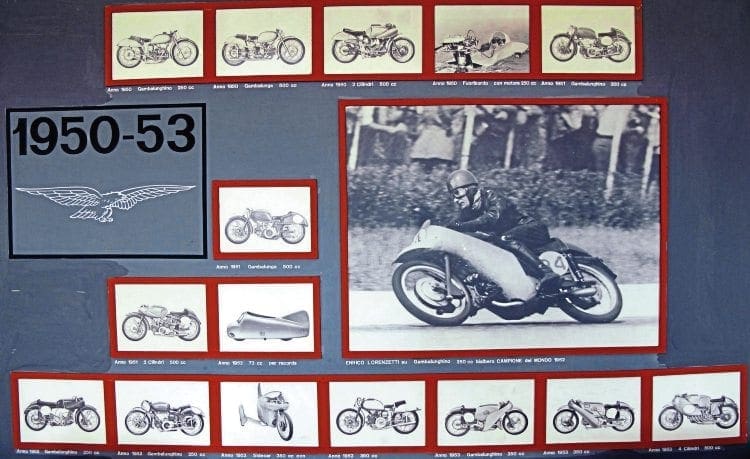

GUZZI’S BELIEF IN mass centralisation and low drag gave them five consecutive 350cc world championships from 1953 to 1957.

These sweet-handling single-cylinder machines, developed in Guzzi’s own wind tunnel, allowed Fergus Anderson, Bill Lomas and Keith Campbell to carry enormous corner speeds on the rough, public road circuits which formed the GP calendar in this period.

It is a joy to be able to get close to these wonderful bikes and admire the craftsmanship.

I took a particular delight in looking at the magnesium alloy fairing on Lomas’ bike, which still shows the working of the English wheel and planishing hammer where the Guzzi craftsman stretched and beat the metal into shape more than 59 years ago.

V8 RACER

PROUDLY POSITIONED ON an imperially raised dais – as well it might be – is the Moto Guzzi Otto Cilindri: Giulio Cesare Carcano’s legendary V8.

Carcano joined Moto Guzzi in 1936 and worked alongside Mr Guzzi until they decided that the single-cylinder race bikes could never compete against the fours of Gilera and MV Agusta.

Carcano designed an eight-cylinder racing motorcycle which was so neat, small, and aerodynamic that it looked barely bigger than the singles it replaced.

With a top speed in excess of 175mph in 1957 – so fast that Guzzi’s factory riders did everything they could to avoid riding the machine – the Otto would have been one of motorcycle racing legends… had Guzzi not withdrawn from GP racing in 1957.

Incredibly, you can stand inches away from the V8 and get even closer to the eight-cylinder engines displayed in the gallery.