WORDS: Stuart Urquhart PHOTOS: Stuart Urquhart

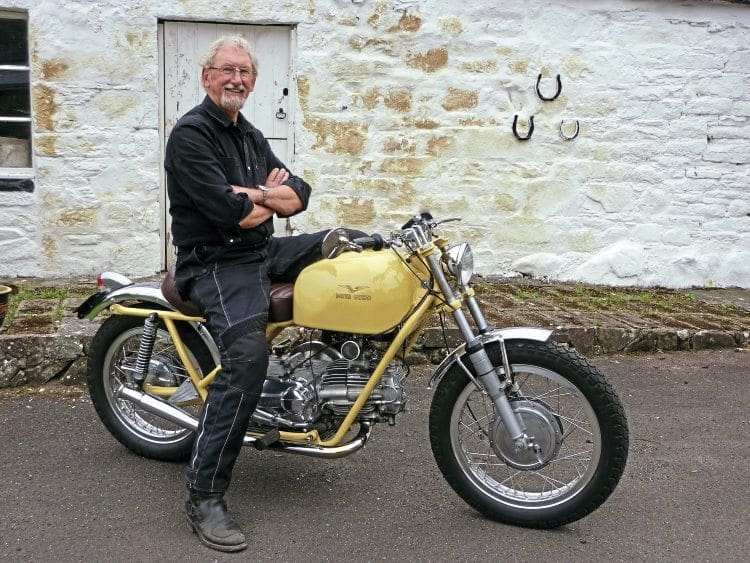

Inside Guzzi’s solid old single there lurked a stylish custom classic, thought owner Tony Adams. So he set about engineering its emancipation…

Tony Adams’ second Moto Guzzi Nuovo Falcone was purchased with the sole intention of turning it into a custom.

Tony had been collecting and bookmarking pictures of custom Nuovo Falcones on Google for as long as he could remember.

Although many inspired Tony, he was determined to create a custom machine that was unique and personal to him. What style and form it would eventually take, he had no idea. So why customise a Falcone in the first place?

“I believe that when Moto Guzzi launched the Nuovo Falcone it was an innovative motorcycle,” Tony replied.

“It was also regarded as an extremely well-engineered machine and became known as ‘Il Motociclo Miloni Chilometro’ or ‘The Million Kilometre Motorcycle’ due to its quality build and outstanding reliability.

Unfortunately, here in the UK the Nuovo Falcone received a bit of bad press as ‘one of Italy’s least attractive production motorcycles’. I wanted to change that perception and create a custom Nuovo Falcone that had kerb appeal and wooed a crowd.”

Tony’s idea to glam up a Guzzi first came to him after he sold his beloved first Nuovo Falcone to a friend and then immediately regretted his decision.

So Tony began searching the internet for another. The trail led him to Lagenfeld of Christchurch, which specialises in buying and selling Eastern Bloc ex-WD equipment. Lagenfeld had just secured a batch of 13 Nuovo Falcones that had belonged to the Croatian Army.

When Tony contacted them, he discovered he was in pole position to have first pick, and just a few weeks later his Nuovo Falcone arrived in full military colours.

“Listed in Lagenfeld’s inventory as a 1971 Moto Guzzi Nuovo Falcone, it was basically complete, but it had obviously been knocked about somewhat, and a few parts were missing,” recalled Tony.

“During negotiations with Lagenfeld I was informed that all 13 Falcones had been stored for 40 years in the Eastern Bloc, so I wasn’t surprised by its bruised and battered state when it arrived in Angus.

Its poor condition and the fact that I’d promised some tinware to another Falcone enthusiast meant that I didn’t suffer any guilt about my intention to convert it to a custom motorcycle.”

Tony’s first task was to remove all the unattractive parts from the military bike. As far as customising the Guzzi, all Tony knew at this stage was that he wanted simple lines and minimalist style.

“I’ve always liked the simplicity of trials bikes and I was partly inspired by Steve McQueen’s raw Triumph in The Great Escape. I didn’t want to create a bobber, streetfighter or flat-tracker as such. I just wanted to create a machine that had a bit of wow factor.

“But in the absence of any firm ideas or a realised design concept, this would be a trial and error build – until I arrived at a concept that I liked,” Tony mused.

“I found the project extremely difficult, as every step of the design process involved choice and not all of my ideas worked on the first attempt. I had many design problems to solve that would affect the outcome – unlike the relatively simple process of restoring a classic, which adheres to a factory defined blueprint.

“I was still exploring and testing ideas when I spent a day removing the military screen, crashbars, legshields, luggage rack and panniers, seat, dynamo and its cast alloy drive belt cover, battery, exhaust, instrument console, air cleaner assembly, mudguards, suspension covers and centrestand.

“All the removed parts were then lined up on my garden wall. I picked up each item in turn and simply asked myself: ‘Do I need it?’ If I answered ‘No’, then I binned it. I binned the lot!” laughed Tony. “I then took my angle grinder to the frame and removed all the unnecessary lugs and brackets. Only then did I begin to feel as if I was making progress.”

Unfortunately, the petrol tank’s base was severely corroded. “Porous,” was Tony’s more apt description.

So he contacted a local radiator repair company which cut out the bottom and soldered in a new one.

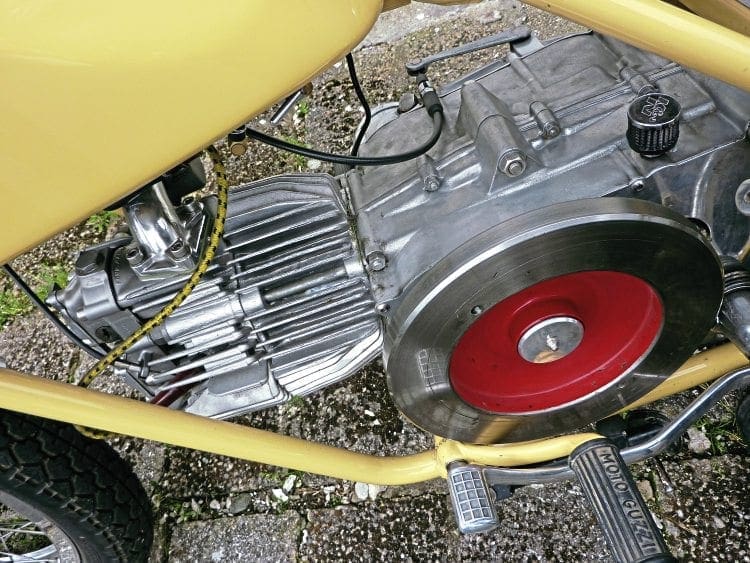

The engine was in perfect condition and was steam-cleaned before being set aside. The engine cases were removed and taken to Lyndene Engineering in Falkirk for wet glass bead blasting – a process which brings them up like new and seals the alloy surfaces for a long-lasting finish.

While the engine awaited the design of its new custom rolling chassis, Tony enlisted the help of his son-in-law, Alfredo, a professional graphic designer based in Pamplona, Spain.

According to Tony, Alfredo is a wizard with Photoshop and helped the project along by visualising and retouching concept images during the custom’s formative stages.

“By morphing custom parts onto the existing chassis images I supplied, the concept bike’s digital forms began to take shape on my PC screen,” said Tony.

“We communicated daily and it was a very exciting stage for me. Alfredo was a great asset and we had much fun visualising and redesigning the concept before I committed to fabricating any custom parts.

“Many digital designs ended up in the recycle bin unless we both agreed that a part looked exactly right on the emerging bike. For example, the headlamp and the saddle designs were each changed three times.

“When we did agree, I would then lock myself in the workshop and make the part. I fabricated the final saddle design from sheet metal before taking it to a local upholster for finishing.

“The headlamp we eventually used is a Bates off-the-shelf custom lamp and is fitted with an LED bulb. Many petrol tanks were tried and tested on the digital bike at this stage and I do remember that a Ducati tank was a strong contender. In the end I reverted back to the original Guzzi petrol tank, which was the better solution.”

While the concept bike was being thrashed out on Alfredo’s screen, Tony sent the alloy hubs to local wheelbuilder Barry Brown in Windygates, to have them polished prior to having new stainless steel rims and spokes fitted.

However, the stainless steel rims were suffering a two-month delay so Tony decided to fit alloy rims instead, “which look much sexier anyway,” winked a delighted Tony.

“Another frustrating delay was caused by ParcelForce, whose drivers managed to lose a package containing my brake backplates and hub covers; apparently because I’d unwittingly entered a wrong digit on the postcode.

“ParcelForce’s Customer Services staff appeared to be well trained in the art of smoke and mirrors and I was forced to source replacement parts in Croatia, only to have my lost hubs returned after I’d submitted my insurance claim form. Apparently they were ‘found’ in a ParcelForce depot.

Meanwhile, during this fiasco I sent off my chrome work to Agbrigg Chrome Platers in Leeds. Engine and alloy cycle parts were also couriered to Scott Hamilton Metal Polishers of Motherwell – all in boxes with the correct postcodes!”

Meanwhile, work on The Beast (as Tony often refers to his project) was moving on apace and colour schemes were next to be explored on Alfredo’s Mac.

After experimenting with various colour schemes Tony had a gut feeling that ‘Sand’ was the right colour choice. Not only did it look different, but the colour was similar to Guzzi’s popular civilian model, the Nuovo Falcone Sahara.

Colour decision made, the leftover parts from Tony’s minimalist purge (including the frame) were shuttled over to Arbroath painter Bob Falconer to be transformed into ‘Sand’.

The mudguards and exhaust were tackled next and Tony takes up the story: “A cocktail-shaker silencer was fitted and a set of drag-style handlebars.

The bars were held by two home-made risers. I also fabricated a set of brackets to mount the Bates headlamp and the front and rear mudguards to the frame.

The stainless mudguards are cut-down stock items sourced on eBay and their stays were pressed from a forming tool I made. This might seem excessive, but my aim was to consider every custom part, as even the smallest fitments would be well designed and exquisitely detailed to withstand close scrutiny.

I would consider I’d succeeded in this regard if my custom fabrications were mistaken for authentic Guzzi parts,” grinned Tony.

Tony is also an exponent of ‘minimalist electrickery’, an area in which he has considerable expertise.

“My intention was always to design a simple electrical system, but the problem was how to make the battery last for several hundred miles without requiring a recharge,” explained Tony.

“The battery I chose for this purpose was a 5aH Lithium Ferro Phosphate type, which is very small and about one third of the weight of a conventional 12V lead acid battery.

“It also has the advantage of a flat discharge curve and will continue to supply 12 Volts until fully discharged, then it goes flat very rapidly – much like an electric drill’s re-chargeable battery.

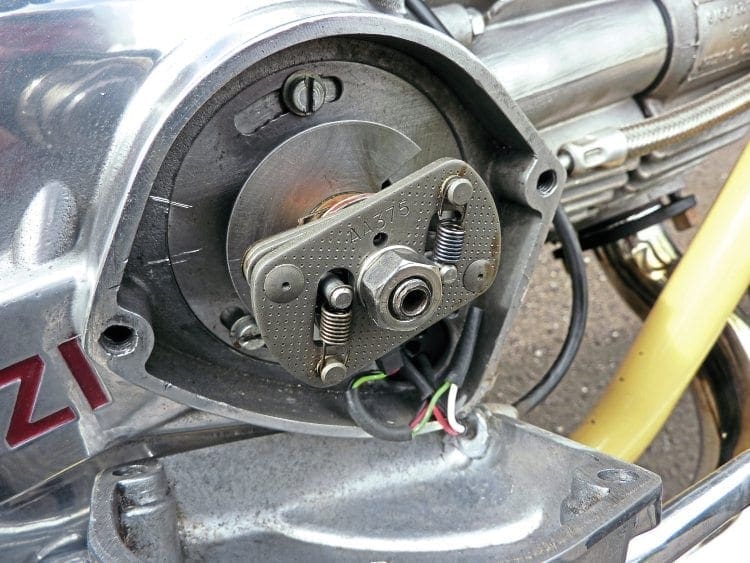

“However, the problem with the factory ignition system was that the points would close for 180 degrees and then open for 180 degrees and, as a result, the battery was discharging at a rate of four amps for half of the time.

An ignition coil only requires five microseconds of ‘charging-up time’ in order to produce a spark. So I attempted to machine a new cam for the points, to close them for only five microseconds at 5000rpm. I failed however, as the mechanical action of opening and closing the points took far too long, so it was back to the drawing board,” lamented Tony.

“Later I tackled the problem with an electronic system designed by a friend who is an ‘old school’ electronic circuit designer. This comprised a magnetic Hall Probe (in conjunction with a slotted steel disc) that sends a signal to an amplifier.

“We then cast the electronic gadgetry in epoxy resin and rubber-mounted it under the petrol tank to protect it against vibration and weather. The system reduces the ignition current ‘on time’ from 180 to 20 degrees, which, in turn, reduces battery drain by approximately 90% (compared to a standard points system). As a result the battery now lasts ‘forever’.

For low current consumption I also fitted LED bulbs to both front and rear lights; the rear lamp is also designed to function as a handy ‘IGNITION ON’ warning light.”

Tony also mentioned that the battery has a theoretical life of around 15 hours before discharging which, in anyone’s reckoning, equates to plenty of time in the saddle. To date, the longest run Tony has logged was a 150-mile round trip without any sign of the battery discharging. A battery charger simply plugs into a flying lead under the seat.

Another piece of Adams’ innovation is the electronic digital pulse speedometer, which is driven by a magnetic trigger attached across two front wheel spokes. As well as a clear indication of speed (mph), the digital device also has a trip odometer.

Finely-made bracketry is always a joy. This holds on the headlamp

There’s not a lot here to distract the rider from the actual riding thing. Nervous types might have wanted a voltmeter…

So how does all this innovative thinking translate when the machine is actually in use? First, a short briefing about the dynamics of the Nuovo Falcone’s gearbox. Tony explains: “When selecting first, then second gear while on the move, it is important to remember that the gear selector will briefly move into neutral as a positive stop, before continuing to second.

So it’s crucial to select the bottom two gears positively and with a deal of patience. Otherwise, if you hurry it is quite possible to jump from first straight into third. The gear selection, however, will soon become second nature with practice,” Tony assured me.

“Another famous quirk of the Nuovo Falcone is its massive, external flywheel. A rapidly spinning mass on the drive side, it attracts much attention, but often deters test rides,” jested Tony.

“But it’s completely safe and virtually impossible to snag your trousers.” I breathed a hefty sigh of relief, because we were off for a joyride shortly. Tony then demonstrated the starting procedure, which is similar to that of a modern Enfield Bullet: ignition on, remembering to glance at the rear light which doubles as a tell-tale and quirky ignition warning light.

Fuel on (no carb tickler), apply full choke (RHS lever), raise the piston over TDC using the left side valve lifter and give the kickstarter a gentle kick.

The engine immediately whispered into life, settling into a steady ka-whump, ka-whump tickover. Remember the phrase ‘fires once every lamppost’?

I reckon this is the very engine that coined that slogan. The gaps between each ‘ka-whump’ are staggering.

“I’m really pleased with the finished bike. I feel it’s turned out very well,” beamed Tony. “Equally pleasing is the engine’s performance which produces plenty of torque, pulling well on an opening throttle.

“She bumbles along quite happily at 55mph. Reducing the rear drive sprocket from 36T to a 31T has obviously helped to increase the top end speed – however I’m certain the light and minimalist chassis is also a factor.

“I’m uncertain of her true top speed, but the law-abiding side of 70mph is quite enough for me. The brakes are bedding in nicely and the Dunlop K70 tyres both look and feel the part. The appreciable weight loss and muscular engine braking is also a boon to rapid deceleration.

“Compared to my first factory Nuovo Falcone the custom version feels very frisky and more willing to stop and go, and the handling is a revelation.

“I’m also delighted with the suspension, which now provides excellent damping and feedback – potholes for instance never upset the ride and cornering has become a real joy. Even my home-fabricated seat is comfortable for the distances I’m likely to be travelling,” said Tony.

“After all, its prime purpose is daylight, back road pottering and it’s certainly no road racer,” Tony shrugged.

“I would describe it as a bobber/chopper/trailblazer mix. When ka-whumping around the scenic roads of rural Angus the bike is sheer joy, the ride is sensational – and that’s the fun.

“When parked I can’t help but stand back and admire its minimalist design, clean lines and gorgeous paintwork. I laugh to myself and think ‘I created that’, and that’s a wonderful feeling. “I feel a very lucky fellow.”

Read more in the December 2019 issue of Classic Bike Guide – on sale now!