When Percy Tait started work at the Meriden factory the last thing he must have been dreaming of was that one day he’d be riding a Triumph in a World Championship Grand Prix. This is how it happened.

Percy Tait started racing in 1947 on a 350 Triumph. When he proved just how good a rider he was, he then raced on borrowed Gold Stars, KTT Velocettes, Manx Nortons and AJS 7Rs. So when he was conscripted into the army and his sergeant heard about his racing exploits, the young Percy quickly found himself in the squaddie’s dream job – riding with the White Helmets, the Royal Signals Motorcycle Display Team.

Jumping Triumph twins through blazing hoops and balancing the full squad on a single motorcycle was the army’s way of showing the public that signing up could mean more than square bashing – for the lucky few.

After Percy was de-mobbed he got a job on the Meriden production line, but his riding skills soon saw him poached by the experimental department as a test rider. And his boss quickly encouraged him to get back into racing at the weekends.

When design engineer Doug Hele left Norton to join Triumph in 1962 (with a brief spell at Ford in between) he was given the job of sorting out the questionable handling of the Bonneville. As chief experimental tester, Percy was the man to put the new unit 650 through its paces and give feedback on the stiffer single-downtube frame and stronger swingarm pivot that Hele designed for the 1963 model. They made a formidable pairing.

Besides riding and racing Bonnies, Tait was also expected to put everything from Tiger Cubs to Tigress scooters through their paces. But one of his favourite motorcycles started life as a Tiger 100.

The Daytona is born

Triumph had introduced unit construction to the twin-cylinder range with the 350cc Twenty One of 1957. A 500 (actually a 490cc) version was offered for the 1959 season, with the same ‘bathtub’ rear enclosure as its little brother. But that was a tourer – it was another year before the first unit construction Tiger 100 prowled the streets.

The T100A was better, but with an over-square engine that should have thrived on revs – the bore was 69mm and the stroke just 65.5mm – performance was disappointing. American and European riders wanted more and in 1962 they got it with the first of the hot Tigers – the T100SS. A good one would produce around 34bhp at 7000rpm, enough for 100mph with a smooth spread of power up to the 7000rpm redline.

Most of Triumph’s twins were sold in America and a win at the famous Daytona 200 race would go down well Stateside. When BSA-Triumph bosses decided to go for glory, Hele had just five months to build six racers, based on T100SS twins. Fortunately, he was able to use his Norton experience where he developed the 500cc Dominator-based Domiracer of 1961. And he had Percy to evaluate.

The new T100R twin-carb specials were sent over for the 1966 Daytona 200-miler. Hele was so determined that his twins would be right for 1967 that he oversaw the race preparation himself. But things did not go to plan. Factory riders like Gary Nixon, Dick Hammer and Buddy Elmore all suffered big-end failures caused by too much oil going to the tappets and not enough to the main bearings.

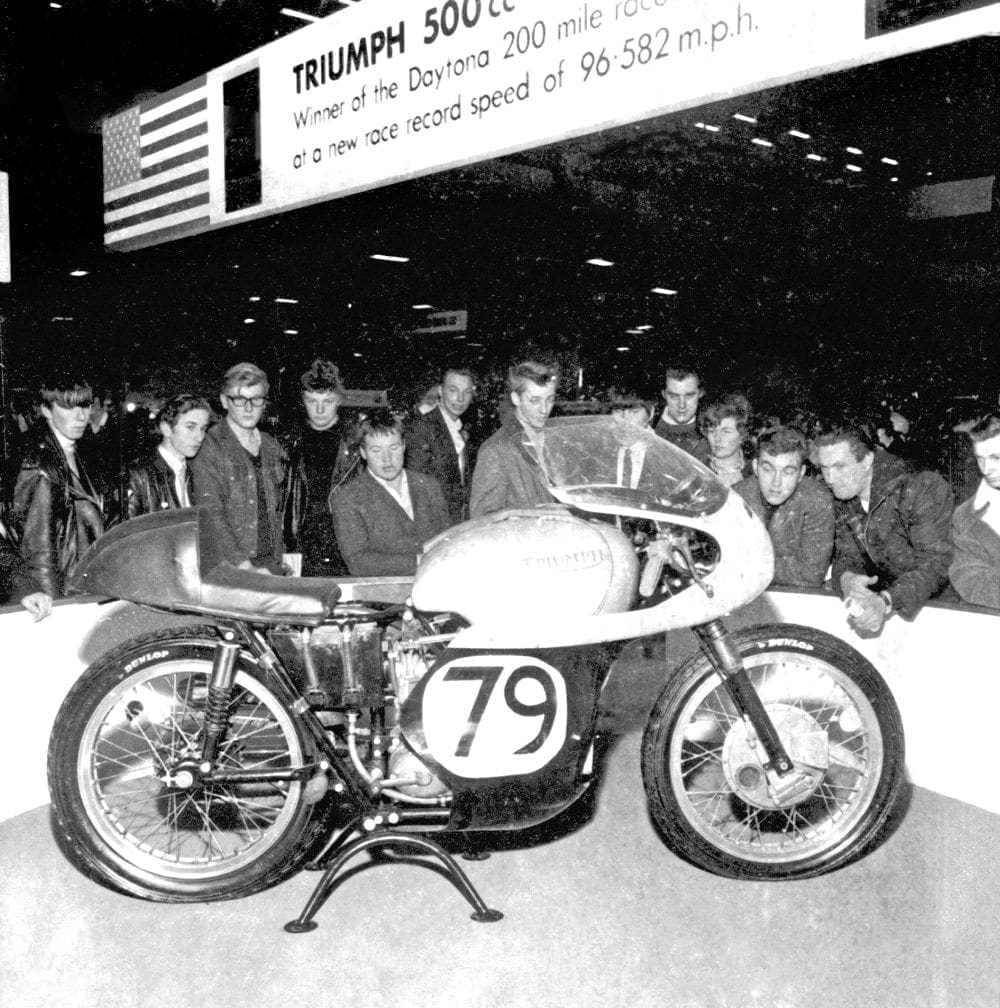

Nixon finally decided to use a back-up bike prepared by Triumph’s Baltimore distributor, while Elmore was left with an engine built the night before the big race with parts salvaged from blown-up engines. But this time it held together, and Texan Elmore took the flag ahead of a brace of 750 flathead Harleys to set a new race record of 96.38mph for the high-banked Speedway track. Triumph couldn’t pass up a marketing opportunity like that, so before the year was out they introduced a twin-carb version of the T100 for the road, called the Daytona.

The T100T Daytona Tiger put out 39bhp from 7400rpm thanks to big 39mm inlet valves, Bonneville specification cams and tappets with shallow radius feet. The exhaust valves were the same size as the Tiger 100, but used steel with a higher heat resistance rating.

Two Amal 27mm Monobloc carbs were mounted on slightly splayed inlet stubs, with the float chamber on the left side Amal supplying the fuel to both carburettors. The compression ratio was a heady 9:1.

Back at Meriden, Hele went to work to sort out the oil pressure problems. Another six T100R specials were prepared for the following year’s visit to Daytona and Percy tested them all, to select the best for Nixon and Elmore. Besides the 750cc Harley-Davidson flatheads, this time the Triumphs would be up against 350cc Yamaha twins and Team Hansen’s 11,000rpm Honda CB450s.

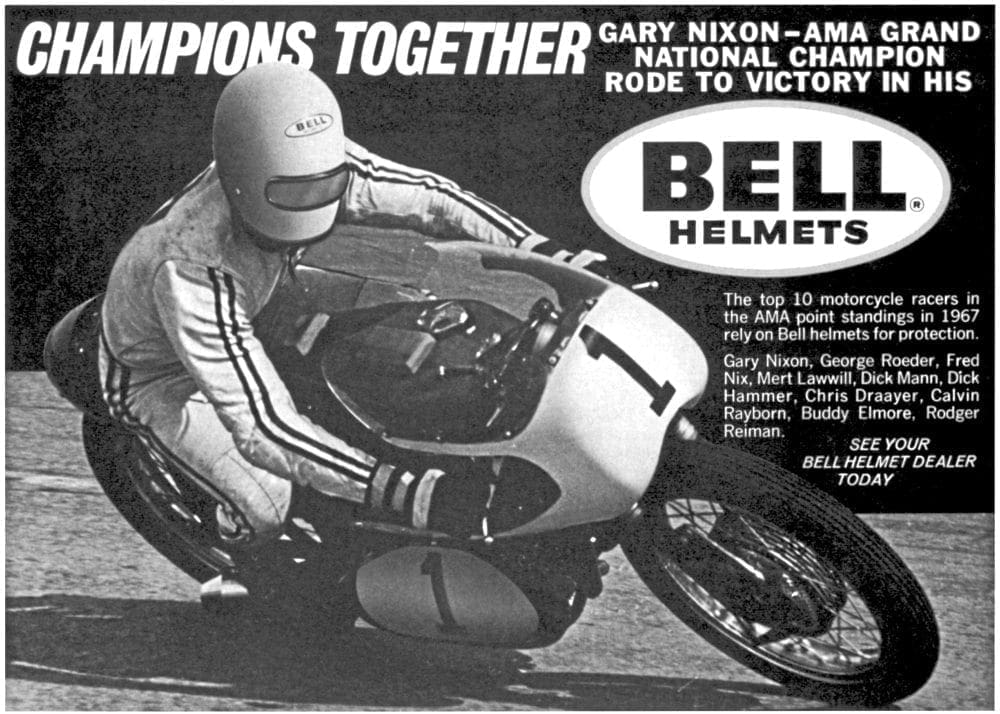

But Hele’s babies performed faultlessly, circulating the Speedway at over 136mph on open megaphones. Nixon won with a race average of 98.22mph for the 200 miles, with Elmore in second place, a lap ahead of the first of four Harleys. The other four Triumph riders finished seventh, eighth, ninth and 10th. And the Japanese threat never materialised.

The final spec

So what did Hele have to do to get that sort of performance out of a 500cc pushrod twin? Simply adding a second carburettor to the T100SS engine, hotter cams and followers, and using bigger diameter hollow pushrods to prevent flexing let the engines rev higher, but Hele was after a good spread of power, as well as top-end performance.

Jack Shemans, the chief test-bed operator, locked himself away in the test house for months on end, searching for an extra fraction of horsepower here and there. He made a note of every modification they made to an engine before running it up on the dynamometer.

So instead of the stock 45° included valve angle, the 1966 Daytona engines had modified heads with 39° included valve angles, and ran a compression ratio of 9.75:1.

Bigger inlet valves passed the mixture from twin 13⁄16in (30mm) Amal GP2 carbs that were flexibly mounted on reinforced 4in (100mm) rubber hoses. These hoses both maximised the induction tract, and helped insulate the carbs from vibration and prevent fuel frothing in the single ‘matchbox’ float chamber mounted between them.

Sparks came courtesy of a special Lucas 3ET energy transfer ignition unit bolted to the outside of the magnesium timing chest cover and driven by an Oldham coupling from the exhaust camshaft. The primary drive cover was also a lightweight magnesium casting, although the cylinder barrels were stock cast iron painted to look like alloy.

Thanks to the use of magnesium castings, alloy tanks and frames made from lightweight T45 chrome-molybdenum tubing (the Accles and Pollock equivalent of Reynolds 531) the Daytona Triumphs weighed just 315lbs (143kg) ready to go – a T100SS weighed in at 337lbs (152.8kg) dry. Power output of the 1966 Daytona racers was 46.5bhp at 8200rpm.

The 1967 engines used a 0.030in (0.76mm) hand scraped squish band in the combustion chambers and a 11.4:1 compression ratio for better gas turbulence and faster fuel burning, without the pre-ignition mice eating holes in the high-dome Manx-style pistons. Inlet ports were also re-profiled, tapering them down towards the valve heads to build up gas velocity.

The stock engine breather was a timed valve in the inlet camshaft that vented to atmosphere, but Hele decided it might not cope with the continued high rpm of a racer. So the timed valve was junked, along with the oil seal from the drive-side roller main bearing. Three tiny holes (1⁄16in or 1.6mm) were drilled in the crankcase wall level with the bottom run of the primary chain, and a length of 20mm bore plastic vent tube was fixed to a hole in the top of the inner half of the chaincase. Now crankcase pressure breathed into the chain case, carrying with it oil mist that lubricated the duplex chain. And because the vent tube was so big, no oil was lost but it ran back into the chain case instead.

Power was increased to 50bhp at 8000rpm. Shemans noted that there was no loss of power all the way to 8700rpm and even at 7700rpm there was 49bhp available. If you let the revs drop to 6500, the dyno still recorded 44bhp, so these babies had the power to pull hard out of corners as well as deliver at the top end.

Handling was improved by lowering the top frame tube by 11/2in (40mm), stiffening the swingarm with gusset plates in the corners, strengthening the steering head and shortening the fork tubes to increase trail. Two-way damping shuttle valves in the forks improved the ride and were adapted for the 1968 production T100 range.

But Hele had to look outside the Triumph parts bin for decent brakes – the 1967 Daytona racers used 81/4in (210mm) double-sided twin leading shoe Fontana drums instead of the puny TR6-style single-sided brakes used in 1966, although the rear brake remained a Triumph 7in single leading shoe.

Daytona success brings momentum

After the Daytona 200-miler, the Triumphs remained in the States so they could be used in American Motorcyclist Association events.

But the experimental department wasn’t going to let all that experience go to waste, and when the Isle of Man Production TT started in 1967, the hot money in the 500 class was on a win for Percy. It was no secret that he would be riding a Daytona that was tuned almost as much as a racer, but in the end it wasn’t to be.

Before the race the engine only fired on one pot and he struggled around the first lap, calling into the pits for a plug change. Leaving the pits, Percy’s red mist came down as he set off down Bray Hill for the second time, but the front tyre punctured when the forks were fully compressed at the bottom, and his race was over.

But it wasn’t the end of his T100 Daytona. It became something rather special.

Percy’s Trumpet was so highly developed by 1968 that he entered the Senior TT. Now there were two separate alloy oil tanks mounted in front of the crankcase. This helped lower the centre of gravity while increasing the amount of oil carried, and as the tanks were in the air stream, there was no need for an oil cooler as used on the Daytona bikes.

The 500 twin was amazingly quick for a modified road bike, and with Percy’s ability to squeeze the last drop of performance out of it he could blow Manx Nortons into the weeds. But an accident before he left for the Island meant that the plaster cast came off his wrist just a few days before his first practice session and he had to be pushed away when starting by his mechanics.

But that didn’t stop him turning in the fastest Senior time in practice, despite atrocious weather conditions.

The sun came out for the race and at the end of the first lap the Triumph was lying in eighth spot. Percy moved up to fifth at the end of lap two, but had to retire at Hillberry with engine trouble. Of course, Agostini and MV took the top honours.

Percy and Hele had high hopes for the 1969 Senior TT where Percy was up against 42 Manx Nortons, 29 Matchless G50s, Suzuki, Honda, Paton and Linto twins, an assortment of hopefuls on everything from a Velocette Thruxton to a BMW or a BSA Gold Star – and a solitary MV triple, in a field of 116 riders. Percy was also riding a Bonneville in the Production TT and during his first practice session, on the short stretch between Sulby Bridge and Ginger Hall, a tooth broke off a second gear pinion in his experimental five-speed transmission. The rear wheel locked up and the Bonnie threw him down the road.

Percy was taken to Noble’s Hospital with a broken collarbone.

Spa – The crowning glory

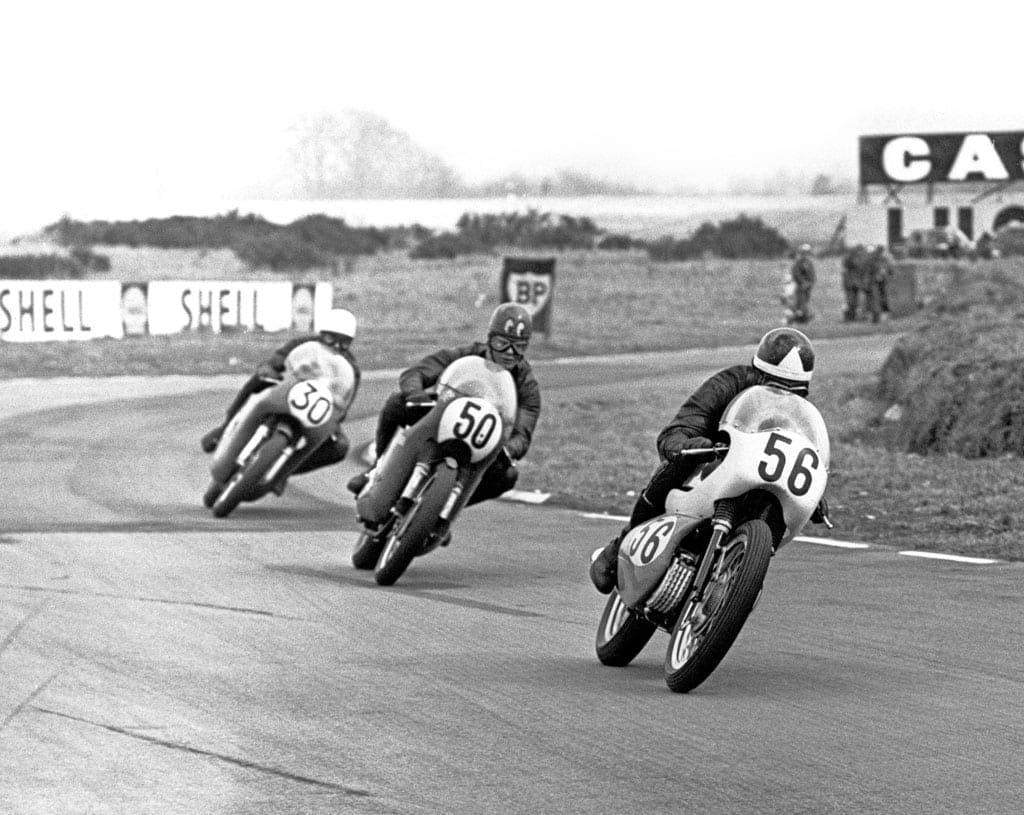

It seems the Triumph rider and his Daytona attract bad luck, but remember this bike was totally experimental – and Percy and his 500 Trumpet weren’t finished. Less than a month after breaking his collar bone, he was at the ultra-fast Spa Francorchamps circuit for the Belgian GP. The virtual disappearance of works teams had taken the shine off the World Championship series, but Percy still managed to inject a bit of life into the 13 laps of the old nine-mile circuit.

Ago cleared off on his MV Agusta triple to win at 125.8mph (202.533kph) but Percy finished second with an impressive 116.74mph (187.88kph) average for the 113.7-mile distance (183.56km), ahead of 15 other finishers. It was a great result at a demanding circuit that just two years later would be shortened, through safety fears from Formula One drivers.

Despite his bravery, Percy wasn’t showered with rewards when he returned to Meriden. Unlike other works riders, he just received his usual test rider’s salary. Some factory aces were even given their bikes after a race, but the best Percy ever got was a Parker pen and pencil set. He was just looked at as an employee doing his job by the management. But he was an employee who was racing in the World Championship, in Belgium, against Ago.

Where is she now?

Percy finally bought his old racer from the factory but when he decided to concentrate on sheep farming, he sold it to Mick Hemmings, a classic Norton and Triumph specialist in Northampton.

Along with the Triumph came a load of spares, including parts used in that 1969 Spa outing and a notebook with detailed descriptions of engine mods over the years. Mick wouldn’t let us copy too much information from the book, but he did reveal that the inlet valves are 37mm and the exhausts 34mm; it uses different tappets to the Daytona bikes, and lightened line-contact rockers.

Titanium valve collars and collets keep reciprocating weight down. The bore has been opened out to 70mm to make this T100 a full 500cc. Of course, the crankshaft assembly and alloy conrods have been polished and lightened and the rocker cover is magnesium.

Although the Amal GP2 carbs have 13⁄16in (30mm) chokes, the inlet port adaptors have 13⁄32in (28mm) bores while the rubber connecting hoses have 1.25in (32mm) bores. Main jets are 230, and full ignition advance is 42°. It all adds up to an impressive 52.5bhp at the gearbox output shaft and an important piece of Triumph history.

Percy and his Triumph 748cc triple

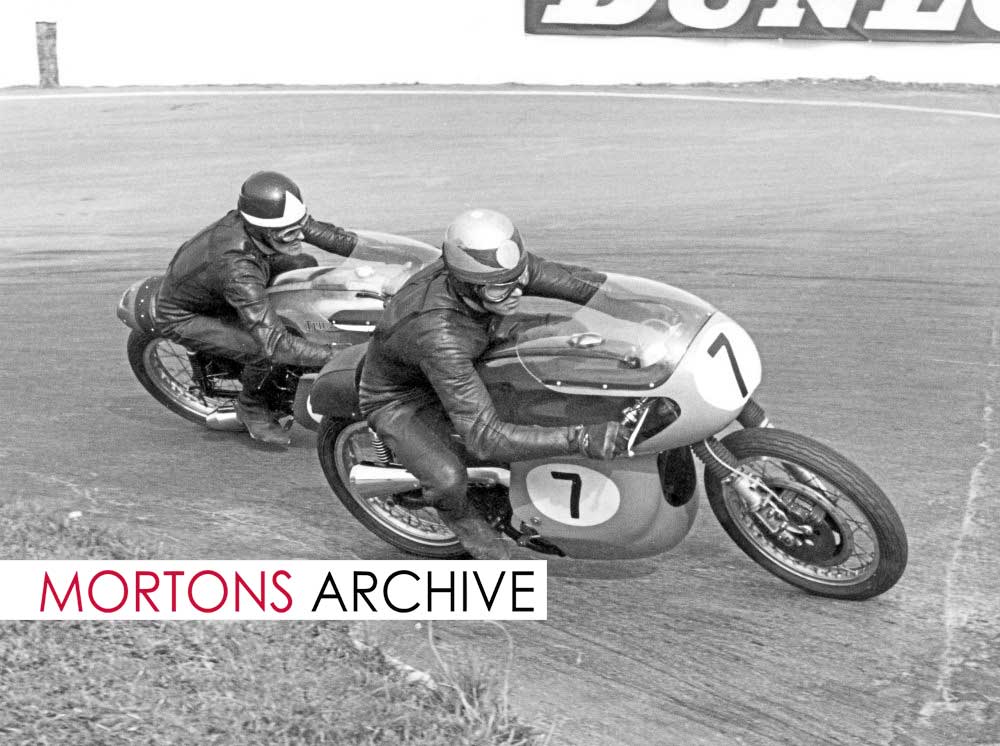

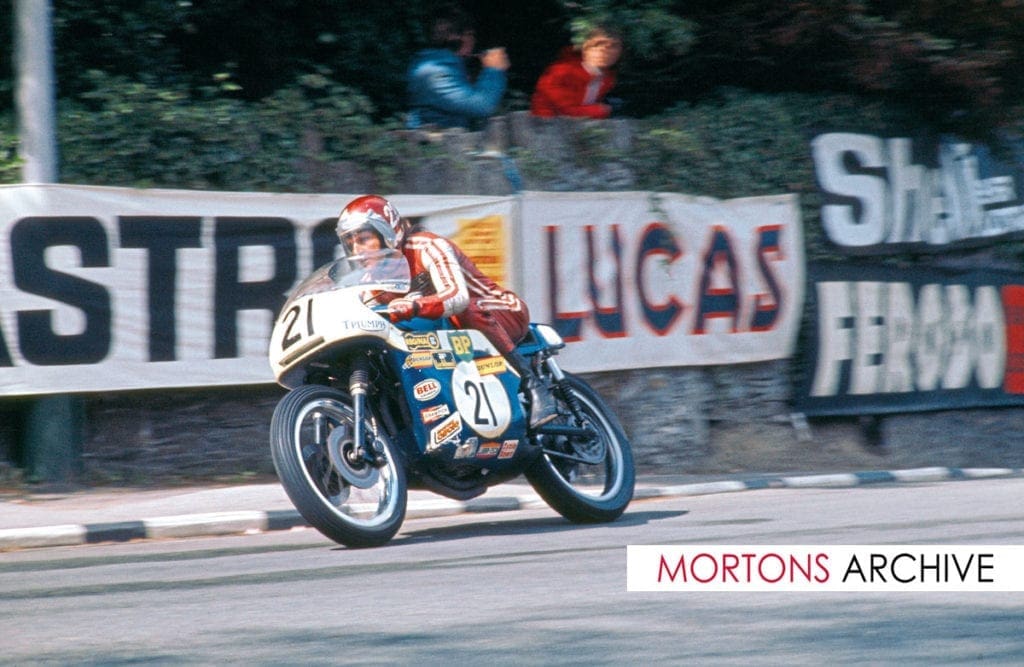

This cracking shot shows Percy Tait on his ex-works Triumph 748cc triple, exiting Governors Bridge in the 1974 Formula 750 race. He finished fourth.

The TT that year was hit by bad weather and the shortened Senior was run on a Thursday, as the Formula 750 bikes were now faster. But despite the name, it was Yamaha that upset the rulebook and locked out the podium, with Chas Mortimer, Charlie Williams and Tony Rutter all riding the overbored, 352cc two-stroke twins that were more reliable and easier to ride in the conditions than the larger machines.

The works Nortons retired, others pulled out and the Yamahas battled amongst themselves. But it was Percy who kept the big triple going, through the wind and rain, for his second best TT finish of the 17 races he started on the Island. Two years later, following growing criticism from riders and the ACU, the TT was stripped of its world championship status. For a copy of this photograph, see www.mortonsarchive.com