We don our boots to have a look at Twin Shock, Britshock, and Pre-65 trials… and wish we’d found this happy world years ago!

Words by Oli Hulme, with thanks to Tim Britton Photography by Matt Hull

Back in the very early days of motorcycling, manufacturers would invite journalists of the day to try out their models in trials – tricky off-road courses that would prove the models’ abilities. This grew into a sport, and soon there were competitive trials all over the country.

Enjoy more Classic Bike Guide Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The basics

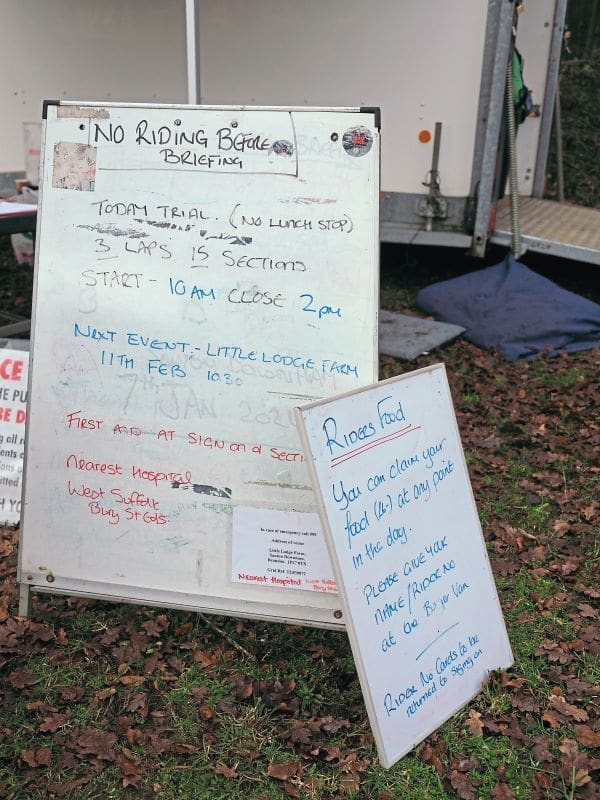

Today, competitors negotiate a marked course made up of several sections. These can be as short as 30 metres or less, and the idea is to get through the section without putting your feet down or stopping. You might get a choice of class: these can be easy, clubman, or expert, which the rider chooses for themselves.

There will be up to 10 sections of varying difficulties in a trial, and each will come with their own challenges – it might be a deep and muddy stream bed, a shale slope, rocky terrain, or on a track through narrow undergrowth.

Observers mark the competitors based on how many times they put their feet down in a section. Get through clean, without dabbing your feet, and you get zero points. Put your feet down once and it is one point, twice it is two, three or more and it’s three. If you fall off, divert off the section, or miss the gate, it’s five points. Then, having negotiated the section, you are on to the next. You may travel the course four times throughout the trial’s duration.

There are classes for all abilities and ages, and no gender-specific ones. Everyone is in it together, from eight-year-old girls to 80-year-old veterans.

There are many two-day events around the country that combine a trial and a social occasion. There are also much longer-distance classic trials, such as the two-day Scottish event and The Beamish. These are similar to trials held when the sport was born in the pre-First World War era and have an endurance element, with riders travelling from 36 up to 100 miles a day.

What will it cost?

You can buy a usable classic trials bike for less than £2000 and then spend a fortune making it better if you want to.

Club membership or AMCA/ACU membership is inexpensive. ACU Trials registration costs £20 a year, and the AMCA has not yet set its fee for 2024. Registering for a trial will cost between £15 and £30, depending on whether you are a member, and the fee covers event insurance.

Petrol consumption is minimal, and you might change your tyres every five years, if you are unlucky.

You will need a van, trailer, or a towbar bike rack to get your bike to events – a towbar rack can be had for as little as £100 or as much as £650. They obviously need the vehicle to have a towbar.

What kit will you need?

■ A basic lightweight trials crash helmet. Many like to stay traditional with an open face, while others are averse to a face full of gorse. Start at £50.

■ Trials boots. These should be as good as you can afford, £130 and up.

■ A pair of lightweight gloves, at £25-plus.

■ A tough pair of trials riding trousers. strong enough to withstand a trip into the brambles, at £50 and above.

■ A long-sleeved jersey and/or a jacket, something tough and abrasion resistant, are £50-plus.

■ Mountain bike body armour for extra protection is lightweight and becoming popular. This can be very cheap, or very expensive, with little in between: £40 to £250.

Riding in a trial

It’s a good idea to take part in an event as a marshal first, helping on the sections, or even as an observer – that way you can learn much about body position and lean, and how to manoeuvre a bike. But remember, each rider has their own style and technique.

To take part as a competitor, you will need to join a club affiliated to the ACU or AMCA, and for the ACU you are likely to need a licence. Or, if you want to try it for one event, a one-event fee can be paid. These are affiliating bodies. and issue event permits and provide insurance for the event and those taking part. You can also join an event as a non-AMCA member, but then your registration fee will be higher. If you want to marshal or observe, you need to be a member to be covered by the event insurance. Some events insist on pre-registration, while others are happy to allow registrations on the day.

What do I do then?

At the start, riders will be set off one or two at a time. They will follow flags to an observed section where they will be given a chance to walk through it and see what obstacles are ahead of them. Is it slippy? Are there any deep holes? They will, once happy, join the queue for their attempt. The observer will indicate when a rider may go: once the front wheel spindle has passed the ‘Begins’ card, the rider is on trial until the front wheel spindle passes the ‘Ends’ card – it’s as simple as that.

What bike should you use?

For classic trials, there are three main kinds of bikes: Pre-65, Twin Shock, and Britshock.

■ Pre-65: As the name suggests, these are based around bikes with engines and some other components made before 1965. The class is mostly British. This class has two and four-strokes, in frames that are rigids as well as sprung.

■ Twin Shock: A motorcycle with twin rear shock absorbers; there is nothing to stop you putting two shocks on the back of a monoshock machine if you want. These are mostly bikes from the 1970s and 1980s.

■ Britshock: New-ish for British-engined machines (the engine almost inevitably one made before 1970) in more modern frames and other cycle parts.

Some of these categories seem to blend into each other.

Mounts for Pre-65s

All the popular British manufacturers made a trials bike at some point and the choice is still wide. You might, if looking for something lightweight, consider Triumph Tiger Cubs, BSA Bantams, Greeves, and Cotton, but you might consider something in a more specialist and competitive frame and suspension, such as Drayton or Beamish. There is all manner of smaller two-stroke, Villiers-engined models, from DOT to James and Francis-Barnett. Those who want something a bit beefier might try BSA C15s or B-series singles and chunky Ariel and AJS, and even Velocette singles are worth considering; though they are a good bit heavier and require some considerable upper body strength, they have the stump pulling torque to get you out of a hole.

Twin Shock machines

Twin Shock riders tend to use the more sophisticated Spanish, Japanese and Italian bikes that dominated in the 1970s, though there are a few Cottons, DOTs and Sprites available.

The Spanish built some brilliant trials bikes in the late 1960s and 1970s – bikes good enough to tempt trials legend Sammy Miller to Bultaco. 250s and above are popular, and Montesa Cotas and Bultaco Sherpas were most common, with Ossa also producing some useful kit. Bultaco machines tend to have the best spares availability and reliability. Spanish bikes are often said to have weaker transmission, clutches and brakes than the Japanese bikes but had a bit more power and superior handling. You can still pick up a usable Bultaco for less than £2000.

The Italians, along with the Japanese, trounced the Spaniards in the late 1970s and 1980s, just as the Spanish did to the British in the 1960s. Notable Italian bikes to look out for are the Fantic 200 and SWM TL models, while Moto Guzzi built trials bikes from its Stornello four-stroke singles. See also machines from Gilera and Ancillotti.

The Japanese manufacturers built some useful tackle, sometimes less competitive than their Mediterranean rivals, but more reliable and easier to live with. Of these, by far the most popular is the Yamaha TY range: reasonably priced, reliable and capable, you’ll still see TY Yamahas taking part in trials among more modern competition. Honda’s TL125, based around the CB125S OHC single, is another useful contender, as are the later TLR200 and TLR250. Kawasaki made the KT250, which was prettier than it was capable, while the Suzuki Beamish 250 and 325 have a strong British connection.

These had a Suzuki engine from their unsuccessful RL Exacta put in a frame made in Brighton by Beamish Motors, owned by former BSA works rider Graham Beamish. The frame design was so good that Suzuki gave Beamish worldwide manufacturing rights for Suzuki trials machines. Today, these can be had for as little as £1500.

Britshock involves the use of bikes with British engines, usually heavily modified, in more modern frames and cycle parts. These are usually home-brewed or made by specialists.

Do it yourself

While you can buy your trials bike, you could also build one. Few Pre-65 bikes are as they came out of the factory – if they ever were. Classic trials offer much leeway for a bike builder. While some may look askance at bikes fitted with many modern parts, for others it’s open season at the autojumble. Most builders are guided by the need to produce as light a bike as possible, with the best suspension allowed. There are specific regulations to meet. There are replica frames out there, and Ariel’s HT5 frame will hold an incredible variety of engines and gearboxes. Drayton frames for Bantams will accept a lot of engines, too. If standard forks are unsuitable, you can put modern internals into them, and put on components from later bikes if you don’t mind sacrificing outward originality, or you can buy brand-new REH ones. Putting an alloy rim onto a Triumph Cub or Bantam hub will save weight, or you can buy replica alloy brakes. And you can do pretty much anything you like to the inside of an engine as long as the outside looks original.

So what’s a good starting bike?

We asked ‘Bultaco Bert’, from the Owd Codgers Club, and he said, surprisingly: “Get a Yamaha TY175. They are phenomenally good, anyone can ride one, they are easy to kick up, and you’re not going to kill yourself on one.”

Bert’s advice is to join a club and go to some trials without a bike first, to get the general idea. He said: “You do get people who go out and get themselves a bike first before they know what they are doing, then fall off and hurt themselves, and decide to give up.

“A club will help you get started. See if you can get someone to lend you a bike at first, and remember that it’s not about speed, it’s about momentum. Bikes won’t do what you expect, and you won’t be going very fast. You need something with a very low tickover and which uses very low tyre pressures – as low as 3psi for muddy ground and 6psi for rocks.

“You’ll never get out of first gear. You need a very slow action throttle and to gear the bike down when you are starting, and to try to ride barely touching the clutch. Staying soft and docile is what you want when starting out. Ride to your own abilities and go out and enjoy yourself. And you will fall off.”

Tips from Tim

Some tips for those starting out, from Tim Britton, editor of Classic Dirt Bike magazine:

1: Walk the route before you ride a section. Look for slippy bits, and holes, and check the rock in the middle of the track – will it move or not? Plan the section in advance.

2: Practice. Take to beer cans and put them on the ground a metre or so apart – now get on your bike and do figure of eights around them, without touching. Keep moving them closer together and try to keep off. Full cans won’t blow away

3: Watch what other people do, but don’t be fooled by what everybody else does – they may be doing it wrong. Don’t be frightened to ask anybody for advice or help.

4: What should you do if you get into trouble? Try and keep upright. And remember that trials is a low-speed sport in which everything happens very quickly.

5: Avoid the light green bits on the grass and you will avoid getting up to your yokes in the mud and spending 10 minutes getting it out again.

6: Tools – I use 13mm bolts as much as I can, so I’ll only need one spanner, a screwdriver to get the carb off, and I use axle nuts the same size as my spark plug wrench.

■ Thanks to Tim for his invaluable help with this article. We couldn’t have done it without him.

My life in trials… ‘by a bloke wot’s been around a long time’

Trials riding has been part of my motorcycling life for more than 50 years, and 2024 marks the 50th year I’ve been a regular rider. The sport has changed in many ways since 1974. In those days, there were only a handful of youth riders – I was one – and we tackled the same sections as everyone else as there was only one route. A course consisted of some hard sections for the experts, some easy for the novice, and most in between for the regular rider. The section was defined by cards with ‘Begins’ and ‘Ends’ on, the route was defined by coloured flags with a ‘red on the right’ rule, and we knew we had to maintain forward motion, not put our feet down, and those doing the observing were retired trials riders who knew all the tricks to be had.

These days, even a club trial has a bewildering number of routes through every section, which can cause confusion. In part, this is because there is an almost equally bewildering number of classes of bike, like Pre-65, Britshock, Twin Shock and so on.

When I started, off-the-showroom-floor trials bikes were pretty good – it was well into the Spanish era, and while there were still the odd Greeves being used, they were rare. Again, in those days, riding kit was simpler, with crash helmets optional, cloth caps still common. On our feet were Dunlop safety wellies, and cotton overalls were common to ride in. Winter trials might see us wearing TT Leathers’ RuffRyda suits. They had lots of lovely colours in the range but were waterproof only in the first trial. Nowadays, modern kit is much better (and available in gaudy colours if you want, though classic black does it for me).

Being increasingly attracted to the Pre-65 scene – so named because the last big British four-stroke, an AJS 350, left the factory at the end of December 1964 – I felt I ought to embrace older trials bikes too. Big bikes like Ariels and AJS were too pricey for my resources but a 350 BSA B40 wasn’t, and while never a great bike in its day, modern tyres and ignitions have opened the door to many hitherto unsuitable bikes. This, in part, is the beauty of classic trials, as almost anything can be pressed into service or built from autojumble bits. The current ongoing Triumph project in my shed fits this bill: cast-off bits, assembled into a bike.

One of the best things about trials as a whole is that fancy and expensive kit isn’t actually necessary. I set myself up to be called hypocrite as I’ve expounded for years that a Pre-65 trials bike should be built from pre-1965 bits, yet the Velocette MAC I rode in the Scottish in 2023 had the engine, gearbox and rider from pre-1965, but the rest was made last week. I do straddle several eras in trials as I still have the last new bike I bought, a 1980 Bultaco Sherpa, and do ride it when an event demands such a bike. I also have my lad’s Fantic air-cooled mono 201, which is an incredible machine of 156cc. These tiny engines punch well above their weight and, in fact, two of us used the Twin Shock version in sidecar trials in the 1980s.

Trials riding is a relatively gentle sport. Things mostly happen at a slow speed, and when you’re in a section it’s generally you alone – unless it’s the Scott – so there’s no chance of being run over if it goes wrong. Though the pace of trials life in the classic world is gentle, it’s still a physical sport, but a rider has the chance to cool down between sections.

Trials riding isn’t horrendously expensive and if you go for the Twin Shock or later classes, bikes are cheap-ish. Like with any motorcycle, if you buy something cheap, work will be needed, so balance the initial outlay with rebuild costs. A financially risk-free way to experience trials is to go to one of the trials schools, such as Inch Perfect or Bumpy, where everything can be hired for the day.

Finally, the bit we gloss over: is it a risk-free sport? No, and nor are many other sports, but risks can be calculated. Is the drop into the section a bit spicy for you as you start out in trials? Well, ask the observer for a five. The hill climb too steep? Poke the wheel into the ‘Begins’ and stop; tackle it later when the experience and ability grows. Eventually. you will look back and think, ‘Why was I worried about tacking such a small hill or drop…?’ Maybe you will advance to bigger events of longer duration, or maybe you won’t and will be happy with a couple of hours on a Sunday with a few mates tackling a few sections in your local club trial. Whichever way you go, trials is a great sport.