We look at the fast two-stroke 250 Samurai and 350 Avengers.

Words and photos by Oli Hulme

As the dust settled from the shake-up of Japan’s motorcycle industry in the early 1960s, a handful of manufacturers were left from the 77 that had existed in 1959. By 1963, as well as Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha, those still fighting their way into the showrooms included Bridgestone, Marusho, Tohatsu and Meguro, but soon these too would be gone. And one manufacturing behemoth was starting to appear in US showrooms: Kawasaki, or in those days, Kawasaki Aircraft.

Kawasaki was making ships, trains, aircraft, tunnel-boring machines and all manner of heavy and light engineering products, including motorcycle engines, which were used by the Kawasaki subsidiary company, Meihatsu Industries, based in Kobe, for a range of machines in the 1950s. In 1959, Kawasaki opened a motorcycle R&D department and then opened a new bike factory at its Akashi manufacturing complex. It partnered with Meguro and then took over the company and launched the first Kawasaki in late 1962, the B8 125cc single. It was a well-made but basic commuter machine. Meguro’s main product, a BSA A7-based (licensed by BSA? We cannot find any proof of that – Matt) 499cc OHV twin, was rebadged as the Kawasaki W1. Kawasaki opened an office in Los Angeles in 1966 to see what the US market was like for its products and soon worked out that economy 125cc singles were not what the Americans wanted – and neither were well-built but dated old twins. Americans in the 1960s craved speed and excitement.

The Samurai arrives

To meet that desire, the Kawasaki designers came up with a 250cc twin-cylinder with disc valve induction and tuned expansion chambers – concepts they borrowed, like Yamaha and Suzuki, from the MZ racers designed by Daniel Zimmerman and Walter Kaaden.

The disc valve on the 250 was a thin, spinning metal disc mounted on the two-stroke’s crankshaft between a side-mounted carburettor and the crankcase. This disc had a hole cut in it that swept across a port in the side of the crankcase, opening and closing this port at precise intervals. This offered better control of the intake port timing than traditional piston porting, providing a clearer flow of the mixture into the bit on a motorcycle that goes bang 8000 times a minute. This greatly improved the way an engine produced its power. With this new powerplant, a ridiculously fast 250cc twin street bike was created. The next issue was marketing it. The firm claimed that the new middleweight (for 250s were middleweights in 1966) would produce 31bhp and could do 105mph. This alone was a heck of a marketing ploy.

Other manufacturers were giving their bikes sensible names, like Dream or Super Swift, or just a row of letters and numbers. Kawasaki, however, was not mucking about: the new 250 was aggressively dubbed the Samurai. It was a big hit with US buyers, and racing bikes won production competitions with the engines breathed on by the factory.

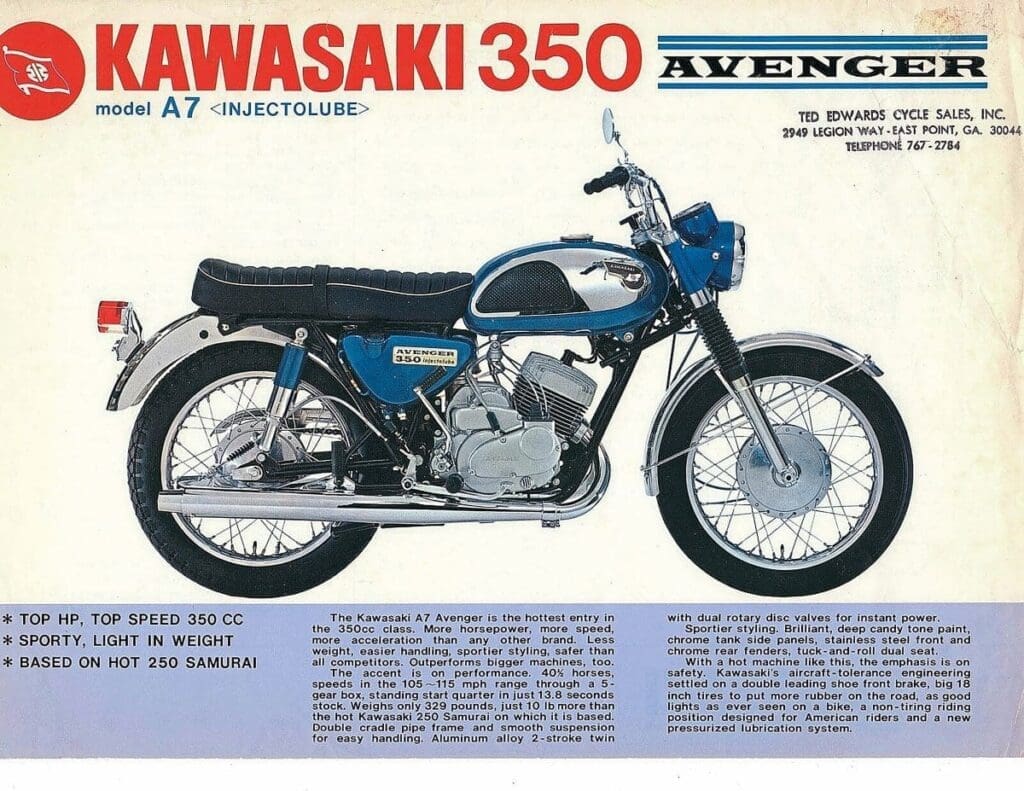

The ultra-rapid 250 was fast, but speed is addictive, and the Americans still wanted more power. Kawasaki then took the Samurai and created a faster 350 model, the even more aggressively named A7 Avenger. This had a considerable power boost from its extra 90cc, up some 30%, to 40bhp on the 250. Kawasaki claimed the Avenger had a quarter-mile time of 13.8 seconds and a top speed of 115mph. Maximum power came out at 7500rpm, and all this came from a 350 straight off the showroom floor. In 1967, the Avenger would keep up with or outrun any British 650 twin… as long as there were not too many bends.

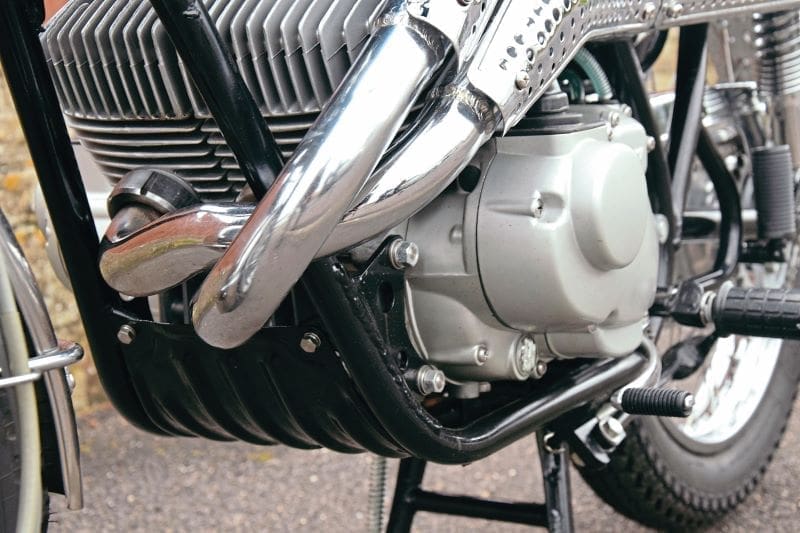

The Avenger engine was a bored-out version of the Samurai, and the engine was boosted to 338cc. Instead of the 250’s 22mm carburettors, the Avenger had two 26mm Mikuni carbs hidden under the engine cases and sticking out of the sides of the crankcase. This made the bikes a rather broad 18 inches wide, so while the engine was short, it was wide too.

By dint of attaching a pair of high-level expansion chambers to the left-hand side and some chunkier tyres, the models became the Samurai/Avenger SS street scrambler.

Despite said knobbly tyres and high-level exhausts, this width did limit the Avenger’s already questionable off-road abilities, while road racers were concerned too, as a high-speed crash could wipe out the carbs. Because the petrol vapour could build up behind the casings covering the carburettors, tiny vents were included so the gases could escape and not catch fire.

The generator and the contact breakers were mounted behind the engine under a finned and ventilated cover, where the carbs would be on a conventional two-stroke. These were driven by the primary drive gears. Relocating the points from the end of the crank made it easier to accurately set up the ignition timing and keep it set up, as those fitted to a long crankshaft running on ball bearings tend to wander. The generator was AC too. Electronic/CDI ignition was added in 1969.

Lubrication was improved on the Avenger and later Samurai models. The early 250 had a system called Superlube, which mixed oil with petrol at the intake ports, while on the later bikes there was a new ‘Injectolube’ system, with oil going directly to the intake ports and with added direct oiling, under pressure, to all the bearings and rod connections along the crankshaft. The system was controlled by a one-into-three cable from the throttle, one cable per carburettor, with the third going to the oil pump. A further one-into-two cable operated the two chokes.

The transmission used a wet clutch and five gears, with neutral at the very bottom, a common feature of Japanese bikes at the time. Kawasaki recommended the gearbox oil should be changed every 1800 miles; 1960s two-stroke oil was likely to leave sooty deposits on the piston crown, so decoking the engine and the exhaust system was also a regular job.

The steel frame had a wide cradle running under the engine and was reinforced by cross braces where needed, providing a stiff, if neutral, design that might have benefited the notoriously hairy handling on the later triples. Up front were up-to-date forks and two steering dampers, one a friction affair through the headstock with an extra hydraulic damper under the tank. Early road versions had shrouded rear shocks, but these were changed to exposed springs later. Eighteen-inch wheels were fore and aft, with a 3.25 tyre at the front, 3.50 at the back. A decent twin leading shoe brake slowed down the front wheel, with a single leading shoe at the back.

The Americans loved the look of the first SS models in particular, though within a year the headlamp nacelle, chromed panels on the petrol tank and rubber knee pads were looking a little dated. The ‘bars on the SS were off-road and the rear mudguard was shortened. The later models had a tank with the signature Kawasaki look that lasted into the mid-1970s.

What’ll it do, mister?

Thanks to the exemplary engineering of the Samurai and Avenger engine, the ride on the Kawasaki twins was smooth and the engine more than powerful enough, while they produced reasonably respectable fuel consumption figures – for the day, at least. The handling was neutral rather than precise. For the modern owner, the engine is pretty tough and forgiving, and the gearbox is as good as any Japanese 1960s machine and better than most. Sensible mods on early models include fitment of the later phosphor bronze swingarm bearings. After nearly 60 years, some bits will have worn out… fuel taps and cables and so forth. The first disc valves were metal, while later discs were fibre bonded composite. It might seem counter-intuitive but these later ‘plastic’ discs are a better bet – when plastic crumbles, it just crumbles, while metal chews things up enthusiastically if it does likewise.

Something that will always be an issue on a 1960s or 1970s Japanese motorcycle is the exhaust header, which has a stub coming out of the head with a thread on it. After all these years, exposed to extremes of heat and weather, these will almost certainly have seized.

There are some real issues with the complex and unusual electrical set-up and setting the ignition timing, something vital with any two-stroke if you want to keep your pistons unholed.

The A-series twins were probably better motorcycles that than S-series triples that replaced them, having more sophisticated engineering and greater reliability. But UK buyers should be aware that hardly any made it into the country, with consequent problems of spares supply today. Buying a basket case is not advised. A complete bike is what you want, even if it’s a non-runner.

The bikes were shown off at the Earl’s Court Show in 1967, displayed by the official Kawasaki concessionaire, C. Itoh & Co. Ltd, which imported some bikes that made their way into a handful of UK dealerships, but few of the twins arrived in the UK officially or even unofficially in the 1960s. Any bike you find today is likely to be a US import, as by the time Kawasaki had established its own Kawasaki UK operation in 1974, the twins were long gone.

Restoring one today will be very satisfying but requires deep pockets and considerable patience.

What did the papers think?

In 1968, Motorcycle Sport got its hands on the very first Avenger to arrive in the UK. It is fair to say that the road tester, one RTM (MS writers were known solely by their initials), was impressed. “On the face of it, this Japanese newcomer was difficult to fault on any count,” they wrote. “Breathtaking acceleration is a well-worn cliché, but in this case, it was really true. Open the throttle in bottom and watch the rev counter needle swing towards the red mark at 8000rpm. At about 5000, the steering seems to lighten. Momentarily you wonder why, then realise it’s because the front wheel is off the ground… Handling was excellent. Ice, slime and mud were encountered during my run, yet never once did I have an anxious moment. Even with the friction damper slackened right off, there was no trace of head shake… This new Kawasaki 350 twin is really so good that, provided it sticks together and wears reasonably well, it is very difficult for one to fault it on any count.”

Rob’s two twins

Rob Askew has not one, but two immaculate Kawasaki disc-valve SS twins from each end of the short production run. The Avenger, the blue one, is a 1967 example, and the yellow and white Samurai is a 1971 model. Getting them both into their current condition has been quite a job.

Rob said: “I got the Samurai from a VJMC member in Colorado. It was complete, but the seat was shot. The chrome was good, and the engine turned over. It turned out that the engine had been run on Castrol R and all the seals just fell out as it came apart, as well. The Castrol had jellified inside, so everything had to be cleaned off. I had the crank rebuilt, and the bores are running on new rings. JBS recreated the original paint. I got a new loom from Kawasaki Triple Parts. Although it was all apparently working, I wasn’t getting any sparks, but that turned out to be an original broken wire where it connected to the CDI boxes. Originally, the indicators used 12v 8w bulbs, which are now unobtainable. But if they were replaced by modern 21w bulbs, the 8w relay wouldn’t make them flash, and with a 21w flasher relay, the way the electricity was produced would make the bulbs flash too fast, because it is set to work with a fifth bulb in the speedometer housing, so an extra bulb was hidden inside the headlamp shell to slow it down.

“Setting the left-hand carb is a challenge too, because it sits behind the same cover as the wet clutch, so you can’t run the engine with it off, so an older damaged cover was cut in half to cover the clutch while the carb could be tuned.”

The Avenger came from British importer, said Rob: “It all looked in one piece, but it was rusty, and it turned out it was seized, with the engine locked solid.”

It wasn’t just any seizure, either. The left-hand barrel had completely seized onto the block. Of course, he didn’t find that out straight away and Rob first spent an age getting the head off to find that, despite being able to get at things, the barrel was still stuck. This is no understatement: the barrel had split the liner and had expanded. It was so firmly wedged in place that he had to machine the barrel off, including the studs.

Having got the barrel off, he needed a replacement – and the search was interesting: “I asked around for one and one bloke said he had one, but when I asked how much he wanted for it, he said, ‘Oh no, it’s not for sale, I just thought I’d tell you I had one.’ What’s that all about?”

Then, he tracked another down in Japan. “It was 80,000 Yen – which is more than £400 – but I said I’d buy it and offered to send them the money. But the seller wanted me to fly to Tokyo to pick it up, which wasn’t really possible.”

Finally, he came across a seller who had a good-condition barrel in Newton Abbot which they would part with for £50. The only problem with that barrel was that it was standard bore, and the only pistons available were 0.5mm oversize, so the barrel had to be rebored to make it work.

Setting up the ignition timing is something of challenge too; because the generator shaft runs at half-speed, the points cam does too – and that means it has to have four lobes, rather than two, so the timing needs to be set twice for each cylinder, which is far from easy.

The indicators are non-stock – the original Kawasaki indicators, an optional extra, had a lens on both sides.

“The Avenger is livelier, while the yellow one is better to ride and seems a bit crisper. The only real problem is that at 6ft tall, I’m a bit big for them. But for a 1960s bike, they are fine to ride, with the only real issue being that you have to remember that neutral is at the bottom of the box.”

The models

1966-1971 250 Samurai

The Samurai was first available, with a rounded tank in candy red or blue with a two-tone black-and-white seat. An option of low or high handlebars was offered. The optional indicators were unusual, fitted with a lens on each side. Later models saw changes to the colour scheme and tank. A separate speedo and tacho replaced the nacelle. Kawasaki fitted a CDI ignition system to later models. By the end of production, bits from newer models started to appear on the twins and the last twins bore a strong resemblance to the new triples.

1967 A7-350 Avenger

The more powerful A7 Avenger had an updated oil injection system design. Cosmetic differences included chrome panels on the petrol tank. There was a slightly different seat and different silencers between the 250 and 350 roadster models. The Avenger incorporated all the styling changes made to the Samurai until 1971, when both models were dropped in favour of the new S series triples.

Street Scrambler range

The SS models used braced motocross-style handlebars, upswept crossover twin exhausts, and a sump guard. Because of the exhaust, no side panel was fitted on the left. The exhaust on some 1971 models was finished in black instead of chrome.

Parts:

Rob’s hunt for parts has criss-crossed the Atlantic.

Cables

www.carrotcycles.co.uk (UK)

General parts

www.johnnys

vintagemotorcycle.com (USA)

www.z-power.co.uk (UK)

kawasakitripleparts.com (UK)

Rubber parts and lenses

claussstudios.com (US supplier of repro rubber components for dozens of bikes from AJS to Zundapp)

Seats

www.pandkclassicbikes.co.uk

Specifications (Avenger)

Engine: Air-cooled two-cylinder two-stroke Capacity: 338cc Bore/stroke: 62 x 56mm Power (claimed): 40bhp @ 7500rpm Carburation: 2 x 26mm Mikuni slides Transmission: Five-speed, wet clutch, chain final drive Frame: Tubular cradle Suspension: Telescopic forks/twin shock Brakes: 2LS front/SLS rear Wheels: 3.25×18, 3.50×18 Weight: 144kgs Top speed: 114mph Wheelbase: 1295mm

Owners’ Club

Vintage Japanese Motorcycle Club

www.vjmc.com