This complex, diminutive two-stroke wannabe racer is much better to ride than you might think.

Words by Oli Hulme Photos by Mortons Archive and Matt Hull

In the early 1980s, Honda was constantly chasing the engineering answer to performance.

In 1985, Japanese motorcycle designers seem to have become slightly over-enthusiastic about what they were doing.

That year, three of the four – Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha (Kawasaki has always been a bit unhinged) – came out with ridiculously fast two-stroke middleweights, based loosely around their 500cc Grand Prix racers. Grand Prix was a big deal worldwide, though slightly less so in Britain as the nation hadn’t produced the kind of world-beating superstar rider the sport needed since Barry Sheene. Though we did sort-of adopt Aussie Wayne Gardner later on, as he raced for Honda Britain!

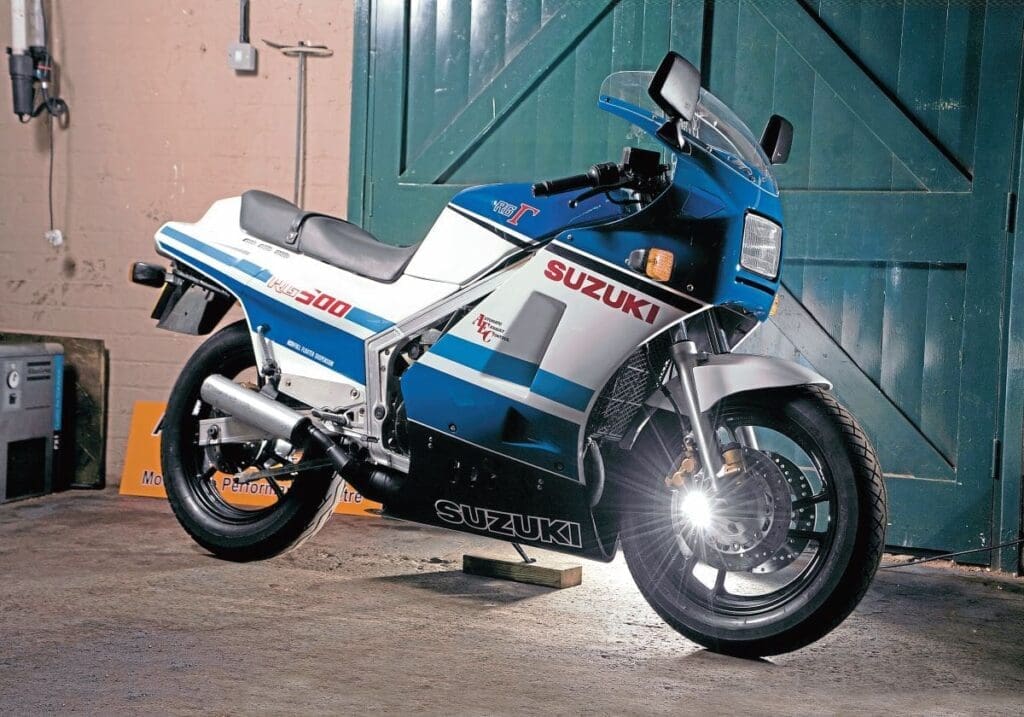

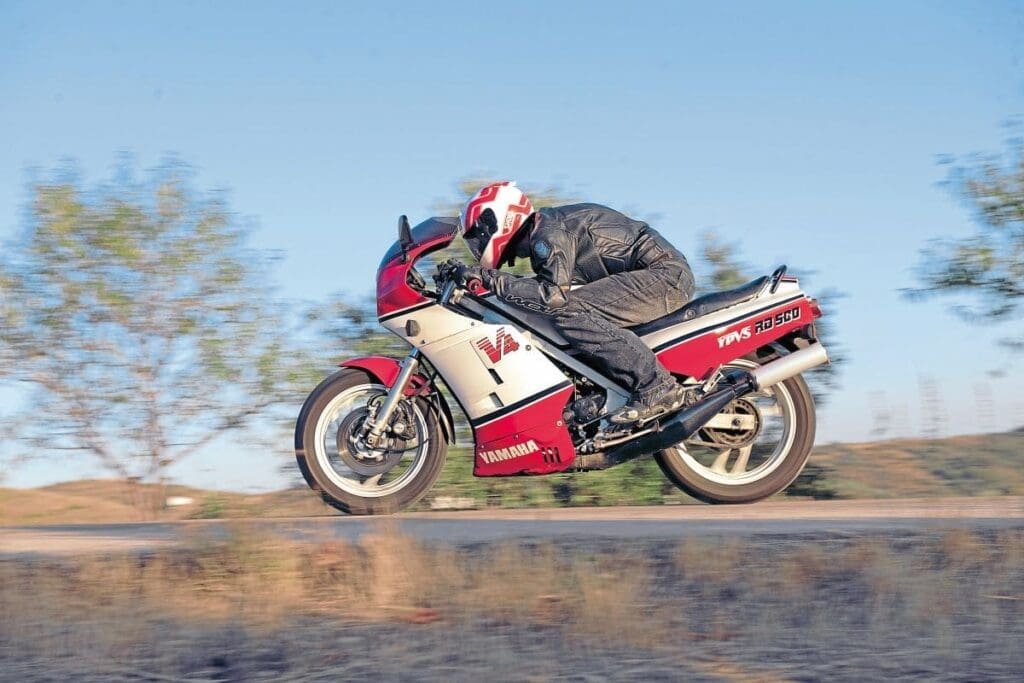

With GP so important to boost sales, Yamaha debuted its new 90bhp RZ/RD500LC square four-cylinder, while Suzuki came up with the 95bhp RG500 Gamma, another liquid-cooled, two-stroke, square four. While the Yamaha was a road bike dressed up like a racer, the Suzuki was a racer for the road, and even shared parts between road and track machines.

Honda didn’t directly respond with this horsepower-waving contest immediately and didn’t produce a bike quite as silly as its rivals on the power front. As a concept, however, the NS400R was certainly out there. A three-cylinder, V3, two-stroke 400 producing a claimed 72bhp (it was actually closer to 55) is hardly sensible commuter bike territory. And Honda PR benefited from the fact that, at the time, Honda’s GP race team were becoming the one to beat.

The 400 capacity for the street bike was chosen to fit in with Japan’s licensing regulations, because Japan was where the large market was. Suzuki brought out a 400 version of the RG Gamma to do the same thing, while Yamaha had the RD350LC YPVS in the same market, a bike that could be tuned to be almost as fast as the Honda but at a fraction of the price (and life-span…).

Of the three race replicas, the Honda was the outlier: it had the least charisma and was never going to be the fastest – for whom that was the most important element. But it was the nicest to ride and by far the most technologically advanced, making up for a missing 20bhp by being nearly 100lb (45kg) lighter that its rivals.

Honda had unenthusiastically dabbled with two-strokes with the MB and MT tiddlers and the H100 commuter bike, but it had no history in performance road-going stinkwheels, unlike its rivals. What it did have was a lot of success in building two-stroke motocrossers, and this is where the technology came from for both the racers and the road bikes. While the NS500 race bike ‘Fast’ Freddie Spencer won the 500cc Grand Prix Championship on in 1983 had an engine with one cylinder at the front and two above at 112 degrees, the NS400F design originated in a one-year only Japanese and Australasia-market model, the three-cylinder MVX250F.

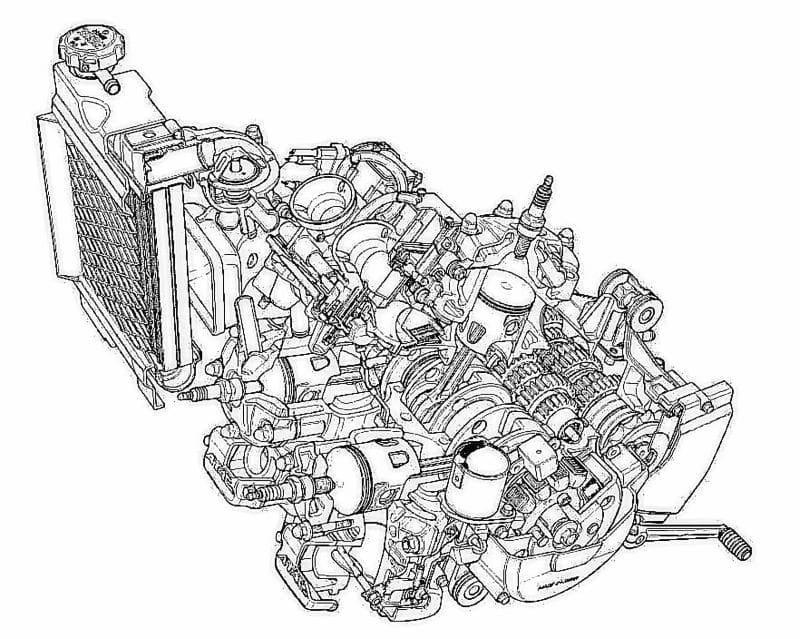

On the MVX and subsequently the NS400R, two of the cylinders sat horizontally at the front while the third was vertical, and a bank of three carbs fed the fuel in. The engine is usually described as a v3, although it could be described as an L3 as, like a Ducati, the cylinders are at 90 degrees to each other.

This three-cylinder arrangement meant that unlike its two square-four rivals, the bike only needed one crankshaft and no balance shafts – and it was much lighter as a result. The arrangement also kept it narrow.

The two-one piston arrangement on the MVX had been very vibratory and Honda tried to resolve this by making the middle piston heavier. This piston had the unfortunate tendency to seize on the 250 but was rectified by the time the NS400R came out. Having the two cylinders at the front and one above meant they all operated in a cooling stream of air, water cooling or not, and reduced the centre of gravity. It meant that the engine’s weight was all in the middle of the bike, too. The upper cylinder’s exhaust ran out through the edge of the tailpiece and the two lower expansion chambers ran along the bottom, giving everything a pleasing visual symmetry.

For nearly 40 years ago, the engineering and design of NS400R is a wonder. The exhausts of the two front cylinders, though not the middle one, had valves that open and close to alter the resonant frequency according to the engines revs, a system dubbed Auto-controlled Torque Amplification Chambers (ATAC).

Honda had been developing hydraulic anti-dive for some years, and the Torque Reactive Anti-dive Control (TRAC) forks had anti-dive valves that progressively stiffened the front end as the brakes are applied, a system also used on more prosaic bikes like the VF400 and CX500.

Stylistically, there was no danger of missing this technical investment. The original bikes had stickers displaying the acronyms and describing the various works of genius, including ATAC on the side panels and TRAC on the plastic covers on the fork legs. There were two colour schemes – either the red, white and blue Freddie Spencer replica with nice big yellow panel on the side of the fairing for a racing number, or the blue and white HRC Rothmans scheme. Many a bike would feature the advertising labels of Honda sponsor Rothmans, too. Even the sidestand had a plastic fairing on it to keep the bodywork streamlined once moving.

On the NS400R, the light weight, short wheelbase and 16-inch front wheel meant that handling was sharp. And the build quality was top-notch, too, as demanded by the Japanese market at the time – if you bought any grey import Japanese 400 in their 1990s heyday, you’ll know they were vastly better made and kitted out than their UK-market equivalents. Like the NS500 racebike, the crank span in special bearings while maintaining a perfect balance. The NS prefix to the model name is claimed to refer to the use of nickel and silicon carbide for the lining on the cylinder walls, commonplace nowadays in most vehicles but advanced stuff in the mid-1980s for all but the latest factory race machinery. Of course, it could just be that ‘S’ is one down the alphabet from ‘R’.

Never the most powerful of the mid-1980s strokers, the Honda triple does have many other attributes that help win the day. The 90-degree crank layout gives a relatively good spread of both power and torque, making it the easiest to ride of the bunch. Although it can potter around all day, all the real performance exists in a powerband between 7500 and 9500rpm. Top speed on the track, where many of the 400s spent their time, was about 130mph. Honda learned much from the chassis to incorporate it into its legendary homologation VFR750R, or RC30 (the Honda code) as it was known.

The fork shrouds tend to stop the brake calipers from cooling off, so the rider does need to watch for brake fade when riding really hard, or they can just take them off and put them somewhere for safekeeping.

Compared to the insanity of the RG and RD rivals, the Honda’s ride is almost refined, very Latin in its smoothness and ease of use which, when allied to such a delightful engine, makes for a big grin factor that the other race-rep strokers only achieve by outright power. They are disarmingly quiet with standard exhausts, too.

The NS400R is a motorcycle that could only have existed in the mid-1980s. Incredibly thirsty, incredibly fast, occasionally fragile, and almost dangerous but safe enough to get you out of trouble as well as get you into it. Only in production for two years, about 12,000 were made.

Today you can pick up a NS400R, the most usable of the mid 1980s two-stroke nutter bikes, for between £7000 and £10,000. That’s £10,000 less than a Suzuki RG500 or Yamaha RD500LC and only a few thousand more than a much more basic RD350LC YPVS. And less than a restored original 350LC.

With only about 100 on the road in the UK, you are unlikely to bump into another one, too.

I rode this one! – Matt

The red, white and blue example you see here is owned by expert restorer Matt Marsham. It is stunning. When he asked if I wanted a go on the cold and damp day we took these photos, I quickly said yes.

It is light, and with its relatively low seat height it feels like you are in control. The perfect – this a Honda – clutch is light, gear changes light enough, and all the controls are where you want to make it all feel instantly familiar. Depending on your usual ride, it feels lacking in torque at first, but that is deceiving as it is pulling much less weight forward than any four-stroke, so the speed is higher than you may think when you look down.

What anyone hearing these bikes on track wants to do is to get into that powerband and then go through the gears in quick succession! Honda’s patented ‘racy, in control, yet comfortable riding position’ gave me confidence and I managed three gears, but I had to give in to the road conditions and sensibility. But it still felt crisp, it felt racy, it felt as I wanted it, like I was catching Fast Freddie.

They are quiet, but I was still aware I was possibly within earshot of Matt waiting for his bike to come back so cruised more sedately. The NS400R will ride like a modern bike, if such a two-stroke existed, but with smoothness and more torque than you may expect. And those small-looking brakes are plenty for the weight, the seating position and suspension calm on the road yet supportive when you brake or accelerate, making the NS a very useable bike. I gave it back to Matt with a smile on my face, but inside I was very envious.

Owners’ Club

Specification

Engine: Liquid-cooled three-cylinder two-stroke Capacity: 387cc Bore/stroke: 57 x 50.6mm Power (claimed): 72bhp @ 9500rpm Torque: 37ft-lb @ 8500rpm Carburation: 3 x 26mm Keihin flat slides Transmission: Six-speed, wet clutch, chain final drive Frame: Box section alloy Suspension: 37mm telescopic forks TRAC anti dive. Pro-Link rear Brakes: 256mm discs, two-piston, floating-calipers. 220mm disc, two-piston, floating-caliper Wheels: 100/90 x 16, 110/90 x 17 Weight: 163kg Top speed: 135mph Wheelbase: 1362mm Fuel capacity: 19 litres